The hiring boom that defined the post-pandemic economy may be losing steam. In its place is a slower, more calculated approach to staffing, driven by economic jitters, stubborn inflation and a hard look at what—and who—companies really need.

Michelline Dufort, who leads the CEO & Family Enterprise Center at UNH’s Peter T. Paul College of Business and Economics, says she’s seeing a shift toward “rightsizing.” During the pandemic, job hopping was rampant, and many companies, after losing staff, realized they could operate with leaner teams, especially given the financial pressures and slower market demands.

Dufort says companies are hiring more cautiously and with a sharper eye on culture fit. That mindset marks a notable departure from the hiring frenzy of just a couple years ago, according to Barry Roy, regional vice president at Robert Half Talent Solutions.

“Business confidence has moderated,” says Roy. Companies are prioritizing niche positions that directly impact growth. In sectors like finance, for example, demand remains strong for analysts and senior accountants. But rather than filling both roles, many firms are merging responsibilities, requiring senior accountants to do much of the analyses.

That kind of strategic consolidation reflects a broader trend. Nationally, the hiring process is taking longer. In a Robert Half survey, 93% of hiring managers said the recruitment process takes more time now than it did just two years ago and 30% admitted to making a hiring mistake during that period. The leading causes for the delays include lengthy application reviews, complicated interview logistics and extended background checks.

For employers like Justin Gamester of Piscataqua Landscaping & Tree Service, those protracted background checks are more than just red tape. Gamester’s business operates in multiple states, including NH with offices in Belmont and Wolfeboro, and employs up to 260 people during peak season.

“I have customers hiring us to be on their property, and so I really don’t want any surprises,” Gamester says. “We’ll take the time it requires to get the information we need.”

Remote work remains a hot topic, with many firms asking employees to return to the office. For some, Roy says in-person work is essential to business growth and developing younger workers. “I just think you can’t do any better than being in-person to do the training and the mentoring of new hires and onboarding,” he says while acknowledging most employers are offering hybrid approaches to balance flexibility with business needs.

For job seekers, expectations haven’t always kept pace with market realities. Wages are still growing, but the dramatic spikes of recent years are leveling out, limiting workers’ bargaining power. In NH, salaries lag those in metro Boston, although so does the cost of living.

“When job seekers don’t have the right expectations, they might end up missing opportunities,” says Roy. He encourages them to not overlook contract roles as they are often a gateway to full-time employment.

Hiring hasn’t stopped, Roy emphasizes. It’s just slower and more deliberate. Companies know they need to hire, but they’re weighing the cost and trying to predict what’s ahead. When they keep a position open for too long, or later decide not to fill it, they strain morale and hurt productivity of the existing staff. In the long run, this affects retention, he says. Roy recommends if companies find someone they like, they should move quickly.

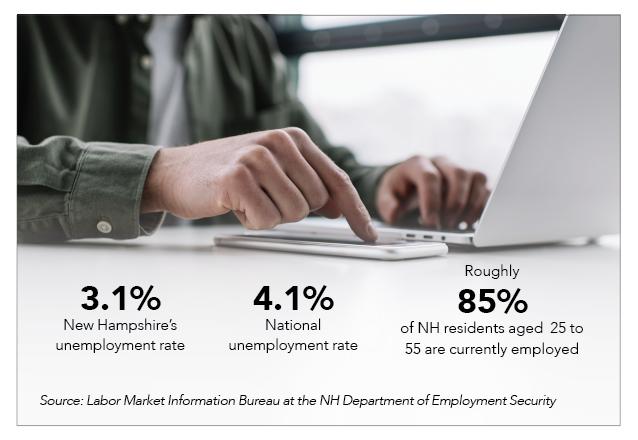

Low Unemployment Rates

Brian Gottlob, director of the Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau at the NH Department of Employment Security, says he’s not seeing a surge in unemployment claims; NH’s unemployment rate is 3.1% and well below the national average of 4.1%. However, the demand for labor is slackening.

Roughly 85% of NH residents aged 25 to 55 are currently employed, a high participation rate by national standards. Still, even as layoffs remain minimal, job postings have tapered and employers are growing more cautious due to national policies creating uncertainty. “There’s some reluctance in making investments, either in equipment, structures, or people,” Gottlob says. “If somebody leaves, maybe that position isn’t immediately filled.”

This cooling in hiring is echoed nationally, particularly among entry-level job seekers. More college graduates are struggling to land their first positions, as employers tighten job requirements and reassess the value of a four-year degree. The share of job listings requiring a bachelor’s degree declined sharply in recent years, according to the Indeed Hiring Lab, which tracks labor market trends.

“Sometimes when the unemployment rate rises, it’s actually not a bad thing,” says Gottlob. He notes that in 2024, a modest increase in NH’s unemployment rate wasn’t driven by layoffs, but rather by more people who were new to the labor force or reentering the market after

a hiatus.

Still, the long-term outlook raises concern for employers. Labor availability is expected to tighten further due to demographic shifts, particularly the aging workforce and a decline in immigration, which historically is a key source of labor force growth. In fact, national data from the Congressional Budget Office shows that most of the labor force expansion in 2024 came from immigration.

“That’s starting to reverse,” warns Gottlob. “Short term, we may have periods where, like now, demand seems to be a little bit lower for any number of reasons. But longer term, we’re going to be facing some shortages.”

Layoffs in Higher Education

Colleges and universities across the U.S., including elite institutions such as Harvard, Stanford, Northwestern and Cornell, are announcing significant layoffs as the sector confronts financial, political and demographic headwinds. Boston University recently cut 120 staff positions and Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) laid off 24 employees. Clark University in Worcester let go of about 30% of its administrative workforce.

The cuts come as higher education braces for a projected decline in enrollment, driven by a long-anticipated drop in high school graduates and a potential reduction in international student visas. Colleges are also contending with rising costs and shifting student demand.

Locally, the University of NH cut 35 positions in May amid broader budget reductions. In a message to the campus community, President Elizabeth Chilton wrote, “Higher education is at an inflection point in this region and across the country.” Chilton cited reduced federal research funding, declining state support and rising operating costs as key factors driving “a considerable gap between projected revenues and expenses for the coming fiscal year.”

Southern NH University, best known for its online programs but with a residential campus in Manchester, followed suit in June, eliminating 60 positions across eight departments. A university spokesperson wrote in an email it was a “difficult decision” made to “responsibly steward the university’s resources.”

Hospitality and Trades Still Feel Hiring Crunch

Even before the pandemic, the trades were struggling to retain workers. Lockdowns accelerated the exodus, prompting older tradespeople to retire early and further discouraging young people, many of whom feel pressured to pursue four-year college degrees, from entering the trades.

“The world of mechanics is shrinking. The world of commercial driver’s licenses is shrinking,” says Gamester of Piscataqua Landscaping & Tree Service.

Another hiring roadblock is the unpredictable availability of H-2B visas, a program that allows employers to hire foreign workers for non-agricultural jobs lasting up to eight months. The visas are capped at 66,000 per year, split evenly between the winter and summer seasons. The cap hasn’t changed since the 1990s, despite growing demand from employers in landscaping, hospitality and construction.

“We’re not taking those jobs away from full-time American workers,” emphasizes Gamester. “We’re filling jobs that full-time American workers aren’t taking.” Gamester relies on these H-2B crews for mowing, pruning, irrigation and general and garden maintenance.

To qualify for the program, employers must advertise positions locally, pay prevailing wages as determined by the Labor Department and meet housing and transportation requirements. H-2B workers also pay federal, Social Security and Medicare taxes.

The resulting uncertainty complicates everything from hiring to scheduling to customer retention. “A lot of the times you don’t really even figure out if you’re getting them again next year,” says Gamester.

Looking Forward

Data from the NH Fiscal Policy Institute (NHFPI) suggests employers are finding it a bit easier to fill open positions than they did in recent years. In February 2020, right before COVID-19 upended the labor market, there were 1.8 job openings for every unemployed worker in the state. That ratio soared to 3.5 by early 2022, as businesses clambered to re-staff. Since that time, the number of jobs per unemployed worker has dipped below pre-pandemic levels to an estimated 1.6 in January 2025.

Of course, there are caveats to this data, explains Phil Sletten, research director of the NHFPI. It doesn’t account for job quality or people working part-time who want full-time jobs. It doesn’t reflect whether open positions align with workers’ skills or career goals.

Still, as that once-frenzied market settles, the mood has undeniably shifted. Companies are no longer racing to fill seats; they’re pausing, rethinking and sometimes choosing to do more with less.