It has been more than a decade since the minimum wage has been raised in NH and at the federal level. Every legislative session since has attempted to increase the minimum, and each attempt invariably went down in a ball of flames.

It has been more than a decade since the minimum wage has been raised in NH and at the federal level. Every legislative session since has attempted to increase the minimum, and each attempt invariably went down in a ball of flames.

New Hampshire is the only New England state to set its minimum wage to the federal level, which is $7.25. On the national level, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders tried to amend the most recent COVID-19 relief bill to incrementally increase the federal minimum wage to $15 to bring it more in line with a living wage. The amendment was defeated in March, and both Sen. Jeanne Shaheen and Sen. Maggie Hassan voted against it. While both senators say they support increasing the minimum wage, they say it should be taken on as a separate bill.

Shaheen told WMUR, “It’s not acceptable for the United States to still have $7.25 as the minimum wage.… Let’s work with some of those industries that are going to be most affected so we see how we can help them make those increases in a way that gets them the employees they need and make sure those businesses don’t go under.”

Bills to raise the minimum wage at the state level this year didn’t fare any better. HB 107 would set the minimum wage at the federal level or $22.50 per hour, whichever is higher, with an exception for tipped employees. That bill stalled in committee. HB 517 would increase the minimum wage in steps to $15 in 2024. Thereafter, the minimum wage would be automatically adjusted based on the cost of living. That too was stalled in committee. And, the NH Senate, in March, defeated SB 136, which proposed raising the minimum wage in the state to $10 in 2022 and to $12 in 2024.

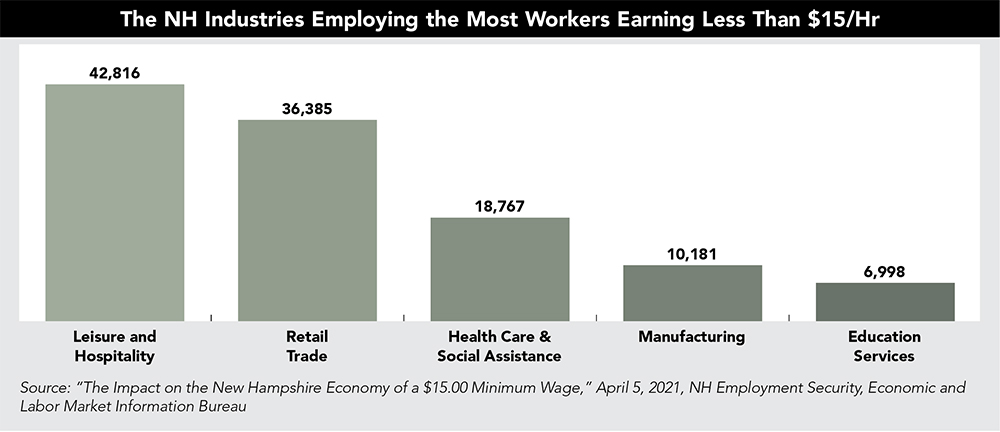

About 11,000 NH resident make minimum wage or below, says Brian Gottlob, director of the NH Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau. But about 144,000 Granite Staters make below $15 per hour, or about 21% of NH’s workforce, he says.

“Market forces are operating in a way that $7.25 is not an option in New Hampshire,” Gottlob says, adding those paying minimum wage are struggling to attract workers especially in Southern NH where workers can find jobs in Massachusetts at higher wages.

So, what would a $15 minimum wage mean for the NH economy? That is the question Gottlob and the Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau, a division of NH Employment Security, attempted to answer in a report released in April.

Report Findings

Gottlob says the debate over the minimum wage is polarizing, and he wanted to provide an objective analysis using data to better inform the debate. “Most of the debate, from my perspective, was coming from an ideological bent or narrower perspective,” he says.

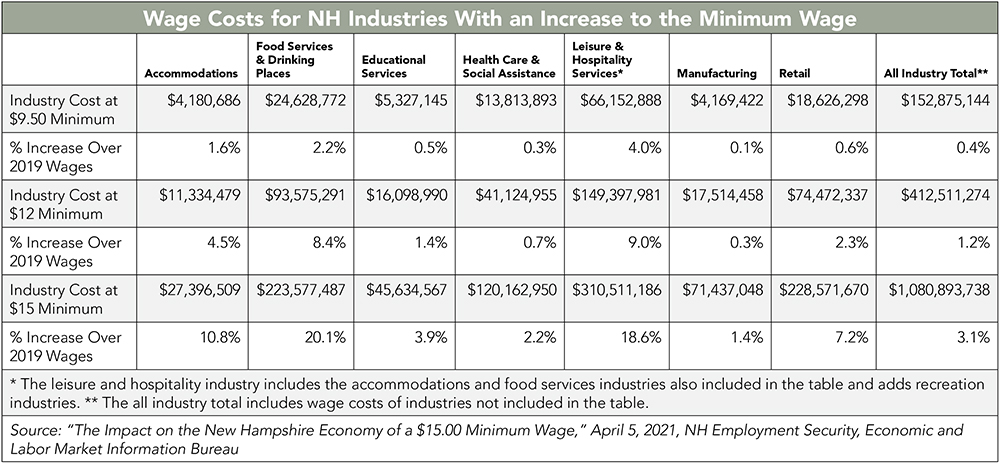

To conduct the analysis, the Bureau used a model that increases the minimum wage to $9.50 in 2022, $12 in 2024, and $15 in 2026. “We used hard data in terms of looking at the number of individuals who work at wages below $14, where they are employed, and the hours they work, and came up with a solid estimate of the impact in different industries and on individuals working in different industries,” Gottlob says.

The Bureau’s analysis indicates increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 would increase wage costs in NH by $1.08 billion over 2019 wage costs, a 3.1% increase. “Nearly one-third of the wage cost increase ($310.5 million) will be borne by leisure and hospitality industries in the state, who will experience an 18.6% increase in wage costs, including a 20% increase in the food services and drinking places industry,” the report states.

The report estimates NH’s gross domestic product will decline by $800 million by 2031 if a $15 minimum wage were instituted, the state’s population will be 9,630 lower, and its labor force will be missing 6,023 employees due to diminished employment opportunities in the state. “People were a little surprised. Some thought the job losses would be higher. Others said there are far more benefits than they thought,” Gottlob says.

Indeed, not all the news is bad. A $15 minimum wage would increase personal income in NH to a peak of $873 million.

And, while the report predicts employment losses will mean personal income then begins to decline, by 2031 it will still be $228 million above what it would have been without the wage increase.

“Workers in the lowest wage categories will see the largest increases in income but also experience the highest number of job losses in response to a $15 minimum wage,” the report states. “Industries such as food services and drinking places, and other leisure and hospitality industries, as well as retail trade, are forecast to experience the largest job losses. These reductions in employment offset much of the benefits of increased wages for low-wage workers in those industries.”

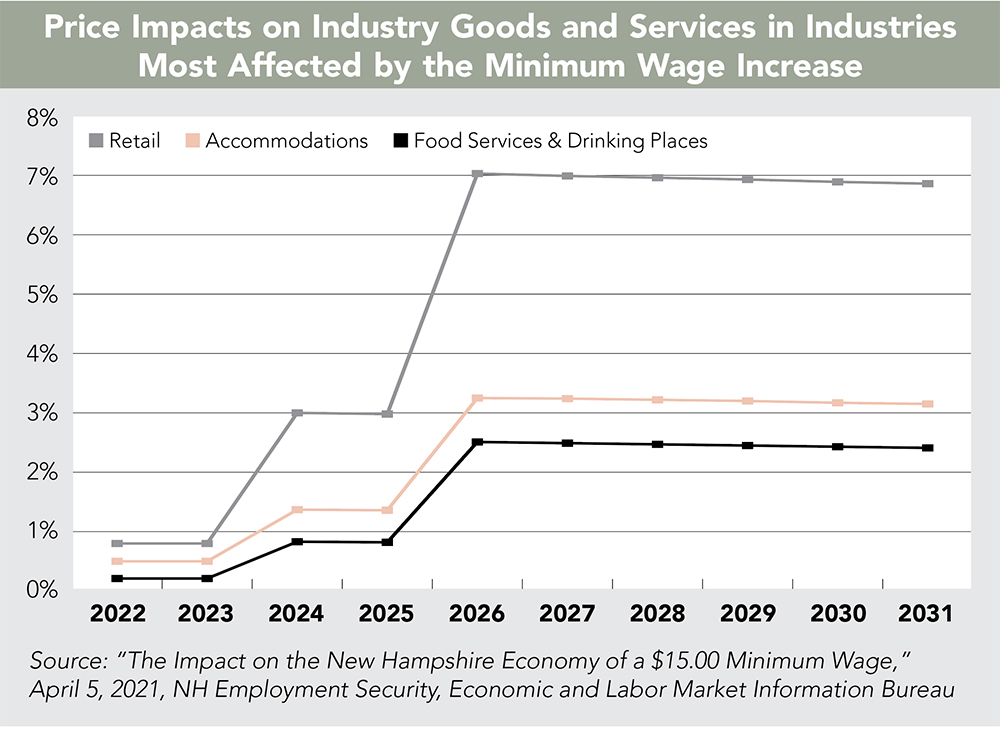

It appears that such a minimum wage hike would have little effect overall on prices of goods and services. The report estimates aggregate price levels will increase by less than 1% across NH’s economy. However, some industries will not be able to absorb the increased labor costs and will have to pass them along to consumers. Costs at restaurants and bars, for example, could increase by 7% and retail would see a 3.4% hike in prices.

“A handful of industries employ 80% of lower wage individuals—hospitality, retail and recreation. They see an impact on prices because the biggest component that goes into business expenses is their wages. As wages rise, businesses have a couple of choices. One is to reduce employment. They can raise prices to offset when possible. They can hopefully increase productivity,” Gottlob say, noting some industries can’t increase productivity. “There’s not a lot of automation in cooking food and serving it,” he says.

Small local retailers have even fewer options to mitigate increased wages, Gottlob says, pointing out they are already competing with the lower prices of larger retailers so price increases are unlikely and big box retailers have already been raising hourly wages to $15 and can better absorb such a cost.

Gottlob says a $15 minimum wage will have a ripple effect, driving up wages overall. “If you’ve worked at a company for five years and you’re making $16 or $17 an hour and the new guy who just got hired with no experience is making $15 per hour, you might feel the need to see a bump. That is a concern.” For some industries, like manufacturing, the jump to $15 will be relatively small as the lowest paid workers tend to make $13 or $14 per hour, Gottlob says.

He says the effect a minimum wage hike would have on NH’s ability to attract new businesses tends to get overblown as the state attracts a diverse range of businesses, including medical manufacturers and pharmaceutical companies, that pay well above the minimum.

Employees could also pay a price for a wage hike as employers could mitigate wage increases by adjusting health care benefits, work schedules, and workplace conditions and amenities.

Another segment of the workforce that will be greatly affected is teens. Gottlob points out NH once had one of the highest rates of teen workforce participation nationwide though that has been declining for years. Where once NH boasted a 60% participation rate of teenagers in the job market, it has dropped to 40%. “That is problematic,” Gottlob says.

“When employers have to pay more for labor, they will expect more from labor. Individuals with less experience and skills will tend not to get hired,” he says.

Tipped Workers

A large part of the debate over the minimum wage in NH involves tipped workers (see story on page 59). There are an estimated 6,203 tipped workers in NH, according to the NH Economic Labor Market and Information Bureau’s report.

Michael Polizzotti, policy analyst with NH Fiscal Policy Institute (NHFPI), says the majority of NH workers making minimum wage are tipped workers.

Currently the tipped wage is 45% of minimum wage. A bill before the NH legislature would freeze the tipped wage and insulate it from increases at the federal level. The NH Lodging and Restaurant Association (NHLRA) supports the bill. Mike Somers, president and CEO of NHLRA, says his organization opposed legislation that proposed eliminating the tipped wage altogether in favor of a universal minimum wage. “Most [tipped workers] don’t want the tip wage to go to $15 as tipping will likely become a thing of the past. They would rather make $18 to $20 an hour in tips rather than a flat $15,” he says.

Given the political climate, an increase of some kind in the minimum wage is likely, Somers says, but he calls an increase to $15 “a bridge too far,” adding an increase to $11 would be more palatable as most of NHLRA’s members are paying that amount or more anyway.

“Our bigger concern is the tipped wage,” Somers says of proposals to eliminate the tipped wage in favor of a straight minimum wage. “We are just coming out of the pandemic with the industry holding on by its fingernails. We need to proceed with caution.”

And the hospitality industry is already paying higher wages due to market demands, he says, explaining outdoor dining is popular again, and many hotels and short-term rentals have been booked solid for the summer since January. “There is not a single proprietor who isn’t looking for help,” Somers says. “I spoke to someone who can’t hire a dishwasher for less than $14. [The labor shortage] has driven up wages to entice people to come back to work.”

Somers adds there are 6,000 to 7,000 hospitality workers still collecting unemployment instead of returning to work. And restrictions on visas are preventing businesses from hiring their usual seasonal overseas workers, exacerbating the situation, he says.

Business Concerns

While raising the minimum wage has not been a “front burner” issue for the Business and Industry Association (BIA), NH’s statewide chamber of commerce, it has opposed attempts to raise it, says David Juvet, senior vice president of

public policy.

“Many of our members are paying far higher than minimum wage,” Juvet says. If the minimum wage is going to be increased, Juvet says it should happen at the federal level to create an even playing field.

However, Juvet says an increase to $15 would have ripple effects throughout the wage spectrum. “It not only increases minimum wage workers, but for those who are making $11, $12 or $13,” he says. “It’s recognizing the reality, which is [businesses] will have to raise prices or cut down on employment levels or reduce profit margins to the extent any of them have a profit margin,” he says.

Who Benefits

Phil Sletten, senior policy analyst with NHFPI, says the majority of lower-wage workers are women and those in their twenties. “Those most likely to see benefits are those with lower family income, lower education, and childless or single parent households,” he says, adding economic models show 20% of health workers and 45% of retail workers would benefit, which are two of the largest employment sectors in the state.

Sletten cites the NH Housing Finance Authority, which reports that the median cost for a two-bedroom apartment was $1,413 in 2020, meaning the number of hours a person making minimum wage would have to work to afford rent for that apartment is 45 hours.

Polizzotti says inflation has eroded the value of a $7.25 minimum wage. He adds NH has the lowest minimum among its neighbors. Rhode Island’s minimum wage is $11.50; Vermont is $11.75; Maine is $12.15; and Massachusetts is $13.50.

Sletten notes that increased wages mean more economic activity from people at the lower end of the income spectrum.

Polizzotti adds, “Minimum wage is a nuanced and complex issue. It affects companies, industries and people in different ways. It can have positive impacts on lower wage workers in aggregate.”

Current Issue - July 2024

Current Issue - July 2024