Skiers explore Jackson XC’s one kilometer of man-made snow on December 31st, 2023. (Photo: Beatrice Burack.)

For people who love winter sports in New Hampshire, this has been a trying winter. Lake Winnipesaukee’s annual Pond Hockey Classic had to be moved for the second year in a row because the ice was too thin. Pond hockey tournaments elsewhere were canceled outright. Ice fishermen on some lakes haven’t even bothered setting up shanties because of thin ice.

Skiers fared no better. As a warmer-than-usual February turned to March, at least three New Hampshire ski areas had to close to preserve snow depth. Cross-country ski areas throughout the region tried valiantly to make the best of scant snow and warm temperatures, but it’s been a slog since mid-December—when the Jackson Ski Touring Foundation would normally have been hoping for base snow and a robust season, it was dealing with dramatic flooding instead.

What seems clear is that climate change is no longer a problem of the future. Its effects are different across the state, says State Climatologist Mary Stampone—sea level rise and flooding on the Seacoast, for instance, or extreme summer heat in southern parts of the state—but for the Lakes Region and northern New Hampshire, the most dramatic changes are occurring in the fall and winter. They’re affecting both the winter economy and, more than anything, the sports that generations of Granite Staters and visitors grew up loving.

For no sport is that more true than for skiing. This is no small deal. While it’s safe to say that New Hampshire is past its heyday as the capital of American skiing, the torch long ago having passed to states like Colorado, the sport still figures prominently in New Hampshire’s tourism industry, culture, and history. According to a 2019 study, the ski industry as a whole contributes roughly $500 million annually state’s economy and generates about 10,000 jobs. The changes it’s contending with now will shape the state and its people well into the future.

But what are those changes? To some extent, the history of skiing in New Hampshire is a tale of one long series of adaptations: to changing tastes, changing demand, changing technology, and changing economics—and to a changing climate. New Hampshire ski areas have dealt with low-snow years for decades. But the big question skiers confront now is different from what’s come before: What happens when low-snow years are no longer anomalies, but the norm? That’s what this series of articles is about.

A starring role in the history of American skiing

When skiing came to North America on the wings of Scandinavian immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th-century, it landed in New Hampshire, where the formation of the Dartmouth Outing Club in 1909 helped propel the sport to national prominence. In his 2007 book The Culture and Sport of Skiing, historian John B. Allen described Dartmouth as “the fulcrum around which eastern Americans learned to ski.” Dartmouth students learned ski techniques from Norwegian loggers settled in Berlin, NH, and from British ski manuals. They and other northeastern collegians took a passion for skiing with them after graduation, going on to found groups such as the Appalachian Mountain Club, the Dartmouth Outing Club of Boston, and the Sierra Club, all of which further spread the fascination with sliding down slippery slopes on planks of wood.

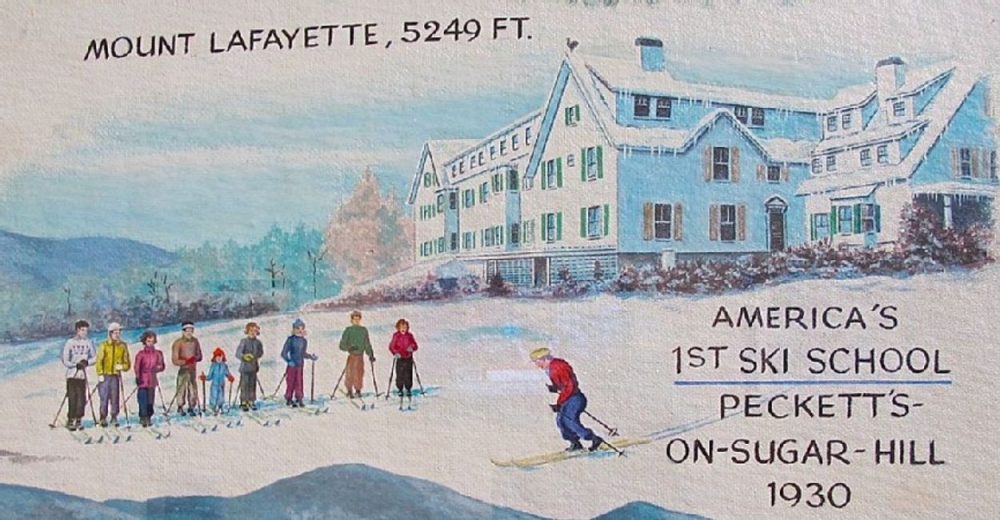

The state’s tourism industry smelled opportunity in the 1930s. Peckett’s Inn on Sugar Hill was quick to grab the trend, says New England Ski Museum Executive Director Tim Whiton. Whiton explains that tourist spots like Peckett’s used to only have customers in the warmer months, until they realized skiing might be a way to entice their clientele to visit year-round.

Today, Peckett’s serves as a wedding venue and no longer offers skiing, but Whiton says it deserves credit for hosting the state’s “the first real authentic ski school,” complete with an Austrian ski teacher.

It was in the ‘30s that skiing truly took off across the state, with rope tows appearing in many communities. “It starts to become, really, this winter sport,” Whiton says.

Peckett’s Inn on Sugar Hill hosted New Hampshire’s first ski school. Card image from a local family history blog, where you’ll also find more history of the inn. (Courtesy of Beatrice Burack.)

In addition to small mom-and-pop rope tows, some areas added T-bars. Other took even bigger leaps forward. Cranmore added its famous skimobile—miniature cable cars on a wooden track that pulled skiers up the hill in 1938. Cannon opened its aerial tramway, the first like it in the country, that same year.

By the ‘50s, there was a veritable “explosion” of ski areas, Whiton says. Another ski boom followed in the ‘60s, which Whiton attributes to rapidly changing technology like ski lifts and better grooming equipment “that lets people ski longer, higher, steeper, more technical terrain.” It also coincided with the baby boomers’ introduction to skiing.

But by the late ‘70s, this all started to change. “From 1975 to 1985 you have 25 percent or more of ski areas, particularly in northern New England, close, never to be re-opened,” Whiton says. The recipe for these lost ski areas, he suspects, was the rising cost of insurance, a greater frequency of low-snow years, and a sprinkle of bad management.

Jeremy Davis, founder of the New England Lost Ski Areas Project, first came across one of these shuttered areas while on a family vacation in the early ‘90s. He’s been fascinated with them ever since, picking up old ski maps from lost areas at antique shops and crowdsourcing information on them through his website. He’s also published five books about the closed areas, including one called Lost Ski Areas of the White Mountains.

“It was a good mystery to find all these places, find out what happened, and make sure they weren’t forgotten,” he says.

Davis has seen areas that closed for all sorts of reasons—changing technology, low snowfall, and demographic shifts after the baby boomers reached adulthood.

A changing climate

Davis’s day job is in meteorology, so when he turns to the present and future of the industry, he sees clearly the intersection between skiing and weather patterns.

“Climate-wise, the variability is just so high now,” he says. “This [2023-24] season started off really well for a lot of areas, and then you get a massive flooding washout from the system that came out of the Gulf of Mexico and caused tremendous damage,” he says, referring to the December 18, 2023 rainstorm that flooded much of the state.

Davis doesn’t remember the winter being like this when he was a young skier. “The extremes are just all over the place. I don’t remember any other flooding events like that happening in December that would wash out roads like that.”

Among climate scientists, too, there’s no doubt that warming winters are affecting the state’s ski areas.

According to UNH professor Elizabeth Burakowski, New Hampshire winters are about three weeks shorter than they were 100 years ago. Her colleague Alix Contosta adds, “We are losing temperatures that are below the freezing point of water.” That’s critical, she says, “because […] it influences whether precipitation falls as rain or snow, and if it falls as snow, whether that snow can stay on the ground.”

This means that ski areas also have fewer and shorter windows in which temperatures are cold enough for snowmaking.

Skiers and ski area staff are clear-eyed about what must be done: make more snow in shorter windows of time. And with bigger investments in technology, they can.

A snow gun blows snow at Pats Peak Ski Area shortly after a rainstorm in late December 2023. (Photo: Beatrice Burack.)

An adaptable industry

Today, downhill ski areas are doubling down on investments in snowmaking, while many cross-country centers are investing in snow guns for the first time and adapting their terrain to low-snow conditions. Backcountry skiers, who pride themselves on their independence from ski lifts and man-made snow, are allying with ski resorts to take advantage of ‘uphill skiing’ on groomed runs.

There’s no question that the state’s 172 lost ski areas serve as a cautionary tale, and it’s a rare ski industry member who doesn’t keep them in mind. But the history of skiing in New Hampshire is also one of resilience.

Jessyca Keeler, president of the industry trade group Ski NH, stresses that New Hampshire ski operators have been dealing with variable conditions for a long time.

“I think what helps me sleep at night is the fact that we are such a resilient industry,” she says. “And we’ve truly had decades to work on that. We’ve got some great experience at all the ski areas, where they’re able to react quickly to changing conditions.”

“There have always been no-snow years or very low snow years when you went into a season with a brand new pair of skis and you came out of it needing to buy a brand new pair of skis the next year because they were just destroyed from low snow,” Whiton, a lifelong skier, recalls.

Snowmaking has long helped New Hampshire ski areas stay abreast of variable snow conditions. “Snowmaking not only changed the game, but it continues to change the game. I would put this one in the industry’s court—and to their credit. They are very efficient at making a ton of snow in 12 hours when they have the right temperatures,” he adds. The question, of course, is what happens when warming temperatures make even snowmaking an uncertain bet—and an increasingly expensive one.

What follows over the rest of this series are snapshots of three ski disciplines—alpine, nordic, and the new, climate-driven pursuit of “uphilling”—as they respond to and think about the effects of warming winters. The final installment will dig into how skiers across the state picture the future of their sport.

Beatrice Burack is a Granite State native and a junior at Dartmouth College working as a freelance journalist in the Upper Valley. Her work has appeared in the New Hampshire Bulletin*, NHPR,* NH Business Review*, and the* Valley News*, among other publications. She can be reached at bea.c.burack.25@dartmouth.edu. Her exhibit on NH skiing in the age of climate change opens in Reiss Hall in Dartmouth’s Baker Library on Monday, March 11th. It will stay up through May.

These stories were first published in Daybreak, an email newsletter focused on the Upper Valley, New Hampshire, and Vermont, and are being shared with the partners in The Granite State News Collaborative.

Current Issue - July 2024

Current Issue - July 2024