Jane and Ralph Earle in their New London home. Photo by Christine Carignan.

When it comes to sustainable energy, Ralph Earle is what you call an agent of change.

His passion for preserving energy sparked in the ’70s, when as a high school student, he waited in long lines to pump gas and “the scarcity of energy was the issue of the day.” Upon graduating from college, he and a group of friends crafted a newsletter on super insulated buildings, which reached 150 subscribers.

Later he broadened his following—and his expertise—to public policy. Earle led the Arthur D. Little’s Competitive Environmental Strategy practice in the 1990s and was a founding director of the Environmental Defense Fund’s Corporate Partnership Program. More recently, he collaborated with other investors to form the Clean Energy Venture Group.

His efforts to conserve energy are reflected in his personal space, too. When in 2013 he decided to renovate a second residence on Lake Sunapee, where he hopes to retire, there was no question about his approach. The stately home, with sweeping views of the lake, was renovated as a net-zero building, to produce as much energy as it consumes on a net annual basis and use renewable energies rather than fossil fuels.

Earle says he sized the solar based on the part-time usage and the house was net-zero except for the past two years when he began living there year-round.

More Affordable and Less Visible

As Andrew Lee of the Seattle-based nonprofit International Living Future Institute (ILFI) says, a net-zero strategy for new construction is no longer the domain of altruistic homeowners like Earle. This is mainly because the cost of photovoltaic (PV) panels has plummeted 99 percent since 1980.

Lower-cost solar PV panels, air-source heat pumps (as opposed to ground-source), heat pump water heaters, better insulation, and dedicated ventilation systems that bring in fresh air from outside and remove stale air from inside are all technological advances that make that coveted net-zero goal more affordable than previously thought possible.

Earle’s Adirondack-style house with brown shingles trimmed in forest green “doesn’t look like a solar house,” he says. Designed by Chris Cook and Bill Maclay, of Maclay Architects of Waitsfield, Vt., it features an open floor plan, natural wood punctuating many of the interior design details, leisurely long covered porches on the second level, exposed wood and stone beams gracing a stone patio on the walkout level, and a two-pitched roof, with a steep section to allow snow to slide off and a less steep roof angled to the sun for optimal efficiency.

The exterior of Ralph Earle’s New London home. Photo by Christine Carignan.

The solar profile on this New London home is indiscreet because while the home looks northwest across the lake, the 39 PV panels sit on the roof’s south side, making them visible to neighbors only when they’re leaving their driveways.

Earle standing on the roof with the home’s solar panels. Courtesy photo.

Though these days, large rooftop panels that shout environmental consciousness to any passerby are not necessarily seen as an eyesore, but to some are an indication of smart real estate investing and long-term savings.

Small But Growing

Lee, who runs the Zero Energy and Zero Carbon building certification programs for the ILFI, says that while net-zero construction comprises less than one percent of the national residential market, its acceleration is on the uptick because of the dramatic reduction in price of PV panels. Yet long-term energy savings is only part of what compels people to buy in to net-zero; some crave the comfortable air quality of a house that’s never drafty or too hot and is devoid of moisture and odors.

With more people investigating net-zero, it is no longer a luxury. “We’re seeing the democratization of solar energy properties—even for folks that can’t afford to own,” says Lee, who mentions the Washington D.C.-based nonprofit Groundswell that’s developed solar projects in the district, Maryland and Georgia, allowing renters to share locally produced solar electricity.

Organizations across the country are trying to disrupt the model where energy is generated at large centralized facilities, and allow folks who rent, but don’t have the up-front funds to capitalize on the trend, to invest in solar power.

An example of this is Tracy Community Housing in West Lebanon. The 29-unit apartment building, which the Twin Pines Housing Trust financed with the support of the NH Housing Finance Authority, is scheduled to open this summer to residents whose household income falls at or below 60 percent of area median income. (For a family of four in Grafton county, that’s around $48,000 a year, according to Andrew Winter, executive director of Twin Pines.)

Tracy Community Housing in West Lebanon designed by Maclay Architects. Courtesy image.

Also designed by Maclay Architects, the Tracy Street building, is sealed to prevent air infiltration, has triple-glazed windows to prevent heat from escaping, and a solar array on the roof that generates enough power to cover the energy load to heat and cool the building.

A net-zero approach is attractive to owners of affordable multifamily buildings as they are otherwise subject to the volatility of propane or oil prices, which affect the break-even point, Winter says. “That creates a real burden for us,” he says, because “we’re limited to pass on [energy] costs to the residences,” since the rents are based on their incomes.

Winter says that while the $7.1 million project costs about five percent more than a similar property without the approximate $300,000 solar installation and other net-zero technologies, it will more than make up that price difference in energy savings.

In December, Twin Pines began pouring the concrete for the foundation. With an easy-to-spot location adjacent to the public library and three bus lines, public interest is percolating for the 18 one-bedroom and 11 two-bedroom units. Winter says he’s already placing names on a waiting list for the apartments; which will rent from $750 per month.

Typically, residents pay for their own electricity. But at Tracy Street, there’s no need for individual meters. “Here it’s all included,” says Winter.

According to Maclay, who authored a book on net-zero building, renewables show promise as the new energy standard. Larger-scale utilities, he says, are looking more at wind and solar than coal, nuclear and natural gas. “[The utilities are] not doing it out of the goodness of their hearts,” he says, “They want to make money.”

Federal tax credits and rebate programs helped nudge the market, but it’s the downward price slope of PV cells that are making fossil fuels no longer viable on a 10-year scale, says Ben Southworth, owner of Garland Mill, a design/build firm in Lancaster. The quantum economics bolster an argument that’s hard to ignore, says Southworth, with the cost of solar dropping about 20 percent every time installed capacity doubles, which occurs every two years.

23 Ammonoosuc’s three-story commercial building, built by Garland Mill. Courtesy photo.

“We’re at the point where the solar and wind cost curve is crossing the fossil fuel curve,” he says. “There’s a lot of disruption in energy markets on a macro level.”

Not Just a Residential Solution

Southworth specializes in the net-zero market and builds mostly residential homes, but is currently finishing up a 9,000-square-foot renovation for 23 Ammonoosuc LLC, a small private company focused on arts and education in Littleton. The three-story commercial building with wide river views has a 30-kW solar array on the roof and a 37-kWh solar battery, which stores the extra energy the solar panels collect during the day when the sun is out, allowing businesses to use that energy at night, explains Southworth. A battery also reduces the amount of energy needed for peak demands, such as when students in the ceramic studio fire up the kilns.

Southworth says combining solar arrays and a solar battery is the next step in transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

Demonstrating That It’s Doable

Last fall, NH Saves, a collaboration of the state’s electric and natural gas utilities that works to support energy savings, sponsored the Drive to Net Zero Home Competition. First prize was awarded to a two-bedroom modular home with a walkout basement in Cornish, built by RH Irving in Salisbury, for a retired couple. (It was designed by Kaplan Thompson Architects of Portland, Maine.)

Participants in the NH Saves Drive to Net Zero Home Competition. Courtesy of Eversource.

The silver, anodized metal-sided home is light and airy with large European-style tilt and turn windows, which the owners can swing inward or upward for better ventilation. The home is not more than 2,000 square feet, but appears grander with its large picture windows and cathedral ceilings.

Built by RH Irving, this home located in Cornish was awarded first prize in the NH Saves Drive to Net Zero Home Competition. Courtesy of RH Irving.

RH Irving custom builds about five homes annually, all designed to minimize thermal bridges (materials that allow greater heat loss), maximize insulation levels, and make the interiors as airtight as possible with no hot or cold spots.

Builder Bob Irving says, “my goal is to show people it’s [net-zero] doable.” He says his homes vary in style and are in the $250-per-square-foot range, as opposed to the $150-per-square-foot cost for homes without net-zero technologies that are built to the lowest minimum building codes. However, he points out that those homes also come with monthly utility bills that net-zero homes lack.

On the whole, homes with and without net-zero energy features may look the same, but “it’s like comparing a 1977 Chevrolet to a Tesla,” he says. “They both get you to where you want to go. But the Chevy is high mileage and is not that great of a car compared to a Tesla.”

Newer Teslas come with price tags in the mid-$30,000 range compared to the more expensive models in the upper $90,000’s. As more manufacturers roll out electric cars, the costs will come down. “The same change can happen with houses,” says Irving, but it may take a subdivision developer in NH to prove that net-zero energy homes are within the reach of the average homeowner.

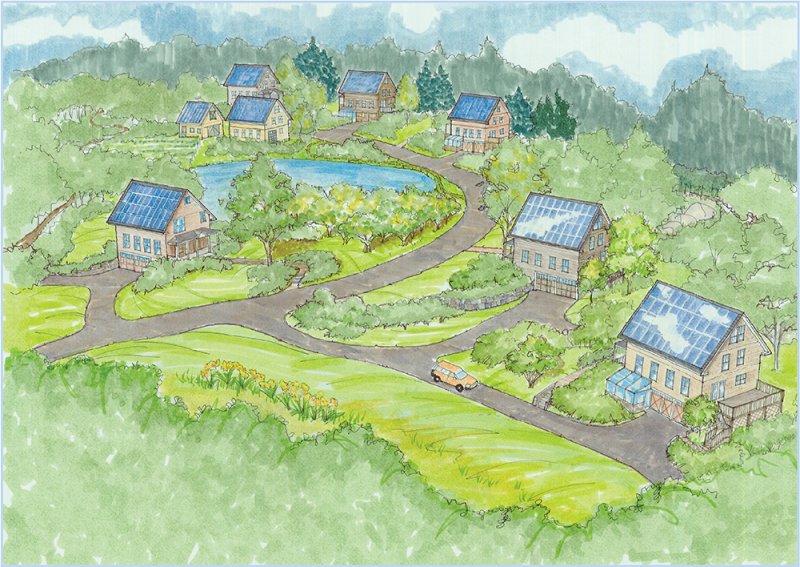

Carter Scott of TransFarmations in Brookline is hoping to do just that. He’s in the early stages of developing two agrihoods, which the Urban Land Institute defines as master-planned neighborhoods with working farms or community gardens as a focus. Both agrihoods will have net-zero dwellings as a baseline, with the option of overproducing to power electric cars.

A proposed zero-energy development designed by TransFarmations in Brookline. Courtesy of Transfarmations/rendering by Karen Fitzgerald, landscape architect.

Both projects are in southern NH, though Scott is withholding specific locations until the sites are approved. The larger development is on more than 50 acres with a mix of housing, such as duplexes, cottages, and single-family homes, all selling between $300,000 and $600,000. The smaller agrihood is less than 10 acres in size.

With the recent report on “Preliminary U.S. Emissions Estimates for 2018” from the Rhodium Group demonstrating that carbon emissions surged 3.4 percent, the largest spike in 10 years, Scott says the only solution is innovation and creativity.

But as technology advances and gets cheaper, simple arithmetic—more than fears about the atmosphere—may ramp up the demand for zero-energy buildings.