Downtown Claremont. Courtesy of the City of Claremont.

Downtown Claremont. Courtesy of the City of Claremont.

Rising up from the southern end of the Upper Connecticut River Valley, the city of Claremont is capitalizing on its manufacturing past to become what local leaders call “a community of makers.”

But these days, what’s being made is not the textiles or paper products of yesteryear’s mill era, but massive bridges, cabinets, IT products, art, precision machinery—and momentum. Despite challenges ranging from a population that skews older to the temporary difficulties posed by COVID-19, the city has been transforming itself over the past 12 years through “very deliberate and forward thinking,” says Nancy Merrill, Claremont’s director of planning and economic development.

The systematic revitalization began in 2009-10, with a three-year, $21.4 million capital improvement project to rebuild roadways, water distribution and wastewater collection systems, and water treatment and wastewater treatment plants, as well as a push to rehab the many vacant buildings downtown. The latter was especially important, says Merrill, because Claremont has a dense downtown, with 51% of the city’s 13,300 residents living there.

Meanwhile, the city has been investing in green energy and in 2018 won the Municipal Energy Champion Award for such projects as the municipal light conversion in 2005, energy audit and municipal building upgrades in 2010, City Center zoning changes in 2013, LED light conversions in 2017 and a water treatment solar project in 2018.

The efforts paid off, starting when Red River Technology outgrew its space in the Lebanon/Hanover area and in 2009 partnered with Vermont developer John Illick and the Common Man restaurant chain to acquire and renovate the former Wainshal Mill on Water Street in downtown Claremont. “The mill had been vacant for nearly 50 years and needed everything,” says Red River COO Dan McGee.

Above: The former Wainshal Mill houses Red River Technology and the Common Man Inn & Restaurant. Courtesy of Red River.

Above: The former Wainshal Mill houses Red River Technology and the Common Man Inn & Restaurant. Courtesy of Red River.

Red River now owns two floors of the mill and leases two others, for a combined capacity of more than 40,000 square feet. The Common Man Inn & Restaurant occupies the first two floors of the building, as well as the old Woven Label mill next door, providing guests with views of the waterfalls on the Sugar River that runs through town.

Soon after that renovation, Jeff and Sarah Barrette bought a former boarding house on Water Street, rehabbed it and moved their screen printing and embroidering business, The Ink Factory, into the 12,000-square-foot space. In 2018, a former Brownfield site nearby on Main Street became MakerSpace, an 11,000-square-foot “gym for the minds and hands,” as co-founder Jeremy Katz calls it.

The MakerSpace renovation cost between $800,000 and $1 million, by Katz’s estimate, with much support coming from government participants. The city sold the old mill building to MakerSpace for just $18.42, and the NH Community Development Finance Authority and the Northern Border Regional Commission each contributed at least $250,000, he says.

A number of local banks and organizations also purchased tax credits.

Today, MakerSpace’s 100-plus members have access to common areas containing “the type of equipment everyone would dream to have in their garage,” says Katz. “There are laser cutters and 3D printers and welding equipment, a ShopBot, routing machines–a lot of precision high-tech stuff used in metalworking and woodworking and the technology trades.”

The space acts as an incubator. “Often people start their endeavor at MakerSpace and as it becomes more successful, they might rent space in the immediate Claremont area,” he says. “The downtown is more successful by virtue of our continued investment and presence here.”

As growth continues, many city leaders foresee an increase in tourism and increased visitation at places like Moody Park (the 175-acre estate donated to the city by a former shoe baron), the volunteer-run Arrowhead Recreation Area and the downtown itself.

Runners in Moody Park. Courtesy of the City of Claremont.

Runners in Moody Park. Courtesy of the City of Claremont.

“People come in to walk on the rail trail or ride their bike in Moody Park, and they’ll stop and get something to eat. It’s just not shopping anymore,” Merrill says, explaining the downtown has a dynamic mix of businesses and services that provide an experience beyond shopping.

Business Friendly Resources

The local River Valley Community College, offering courses in advanced machining, computer technology and health care, is another valuable partner in job training, Merrill says. “If we have a company struggling with workforce, we can call over there and say, ‘can you meet the company with us and see if there’s something you can provide?’” she adds.

Merrill credits former longtime City Manager Guy Santagate with providing the stimulus for some of the city’s growth, through establishing processes like “one-stop shopping” that put the building inspector, city planner, grant administration and economic development into one office, making it easier for businesses contemplating a move to town.

All the activity ultimately provided a “tipping point” that started to draw even more businesses to Claremont, says current City Manager Ed Morris. Morris’s hiring is itself a testament to the city’s turn-around. Previously the town manager in Weathersfield, Vt., just across the Connecticut River from Claremont, Morris says he and his wife came to Claremont often and started noticing a new vibrancy in the downtown area a few years ago. “When the opportunity [for the job] became available, I wanted to become part of the excitement and growth in the city,” says Morris, who assumed his position last September.

Investing in the Arts and Housing

Mayor Charlene Lovett says Claremont is on the rise. “People in the community are coming forward with solutions as far as expansion of cultural arts, taking buildings that have been vacant since 1995 and refurbishing them for cultural purposes,” she adds. One example is the planned renovation of 56 Opera House Square, a building next to City Hall that has sat empty for 25 years, into a performing arts and education center.

Plans for the $2.7 million project call for a performing arts venue and commercial kitchen on the first floor, an education center, open arts studio, gallery and reception space on the second, and a performing artists’ retreat on the mezzanine, according to Melissa Richmond, director of the West Claremont Center for Music & Art. The organization, which offers live performances and music and art education, is currently headquartered at the Union Church and offers about 50 events annually.

It has partnered with the Claremont Development Authority, which owns the proposed new site at Opera House Square, with the hope of completing renovations by 2021, according to Richmond. The Authority will be renovating the building’s envelope while West Claremont Center for Music & Art is responsible for the fit-up, she says.

The project has been helped by a community development block grant of $500,000, as well as $400,000 in tax credits, and “we’re looking at 25% to 30% private donations,” she adds. “We’re getting close to halfway there.”

The arts center is one of several new or ongoing projects in the city, many of them relying on public-private partnerships.

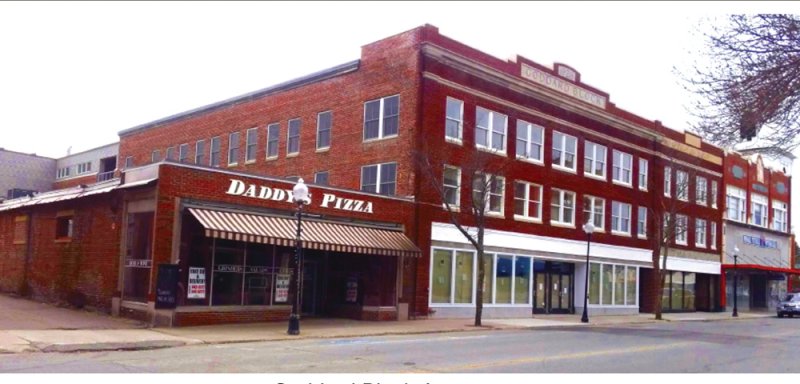

Lovett points to work on what was called the Goddard Block, a historic downtown building that was condemned for fire and safety reasons. Developer Kevin Lacasse, CEO of New England Family Housing, gutted and refurbished the historic structure in early 2019 to provide 36 new apartments and commercial space at the street level.

New England Family Housing refurbished the condemned Goddard Block building into apartments and commercial space. Courtesy of New England Family Housing.

New England Family Housing refurbished the condemned Goddard Block building into apartments and commercial space. Courtesy of New England Family Housing.

“That represented more than an $11 million investment,” Lovett says, “which the (city) council assisted through a 79-E program.” That state program, also called Community Revitalization Tax Incentive RSA 79-E, allows developers to ask city council to freeze the assessed value of a distressed property for a certain number of years, so they do not have to pay increased taxes as they improve the property. When the period is up, taxes are paid on the current assessed value.

“You’re not losing any tax revenue because you’re freezing it, but you’re giving them some relief,” explains Lovett. “With traditional New England mill buildings, you don’t normally have that kind of money to invest unless you can put together a package of financial incentives.”

The project also benefitted from a variety of state and federal funding programs, ranging from low income housing credits and historic tax credits to a community development block grant, according to Lovett.

Robust Businesses

Another relative newcomer to Claremont is New Hampshire Industries, or NHI, which moved its headquarters four years ago to a 130,000-square-foot facility off River Road. The company, with 120 employees, makes mechanical power transfer products, including idler and drive pulleys, blade adapters, timing pulleys, machined components and custom assemblies.

Company President John Batten says New Hampshire Industries turned to Claremont when it sought to expand and consolidate its operations in Lebanon and Wisconsin because workers were more available and building costs were less expensive than in Lebanon.

The firm, whose tag line is “we are makers,” was acquired in late 2019 by the manufacturing group Makers Forward, which seeks to make New Hampshire Industries its platform business as it executes other acquisitions, Batten adds.

“Within the next one to two years, we will likely see additional growth,” he says. “We are also expanding our product offerings, which could lead to significant growth within our organic company.” Batten is also president of the board of the Greater Claremont Chamber of Commerce and sees the city as “on the upswing.”

“One of the things, as a senior management team, that we noticed when we were looking for areas (to relocate) was the energy and support we got from Nancy Merrill and her team,” he says. “We really felt good about moving to Claremont and joining an area that is welcoming.”

But it’s not only newly arrived firms that enjoy municipal attention. “We care as much about the companies that are here as much as the ones coming in,” says Merrill. “That’s not always the headline, but it’s where a lot of your tax base is, with existing companies.”

One such firm is Crown Point Cabinetry, which started in a garage on Oak Street in Claremont when Norm Stowell, father of CEO Brian Stowell, was asked to build a set of cabinets for a local family. The company has steadily grown since and is now housed in a 100,000-square-foot facility in Claremont.

An employee at Crown Point Cabinetry. Courtesy photo.

An employee at Crown Point Cabinetry. Courtesy photo.

A maker of custom home cabinetry, the company employs 90 and “my plan is to continue growing the business,” says Brian Stowell. “If Claremont is anything, it is resilient.”

Another longtime Claremont company, North Country Smokehouse, a producer of meats and cheeses, tripled its footprint to 67,000 square feet after it was purchased by a Canadian firm two years ago.

Growing demand also led to an expansion of the 250,000-square-foot facility owned by Canam Bridges, maker of highway and railroad bridges, including the replacement Memorial Bridge in Portsmouth.

Surviving COVID

Like the rest of the country, businesses in Claremont have taken a hit due to the effects of the coronavirus pandemic, but “our companies seem to have gotten through the worst of this,” says Merrill.

She says city officials provided information about available state and federal aid to any establishments that were struggling. Though restaurants in particular felt the economic squeeze during the shut-down, they appear to be rebounding,” she says.

Morris notes that city planning officials worked hard to keep zoning applications flowing “and moved to Zoom pretty quickly” to avoid losing momentum on growth.

“Some of our Main Street-type businesses, which were a lot of the ones who struggled, the community rallied behind them, and some are showing higher than normal [business] now,” he says.

Moving Forward

The city continues to work on infrastructure. His budget for this year includes $200,000 more for road improvements than last year’s. Morris also plans to bring a $4.8 million bond to the City Council shortly to revitalize infrastructure on Pleasant Street, a major thoroughfare and economic hub in the city. It will include separating drains from storm water, adding 12-foot sidewalks and improving traffic flow to make the area more pedestrian-friendly and allow for more outdoor dining and entertainment.

Lovett says that the Rethink Pleasant Street project is especially important to help address another challenge faced by the city: an aging population. “In order to bring in younger people, you have to rethink what downtown looks like,” she says. “They want proximity, ease, vibrancy, cultural arts, good restaurants and retail.”

With the planned changes, she adds, “I think Claremont is going to become a regional economic powerhouse, not just within Sullivan County but between New Hampshire and Vermont.”

Those interviewed agree that the city’s tradition of community engagement is vital to the continued growth. “I was in the military and lived in a lot of places in the world and in the country, and I’ve never lived in a place that was so community-oriented as Claremont,” says Lovett, who points out that businesses like Red River and the Ink Factory supplied more than 100 employees to help with a town-wide cleanup this year.

The city also boasts plenty of business partnerships. New Hampshire Industries is working with MakerSpace to create a workforce training program, according to Morris. Numerous companies, from Crown Point Cabinetry to Red River, have donated money, machinery or teaching time to MakerSpace to aid fledgling entrepreneurs.

Members of the Claremont MakerSpace using welding equipment. Courtesy photo.

Red River also runs a summer program for students in grades eight through 12, who spend two hours a week in its offices learning hands-on technical and career-readiness skills under the guidance of mentors.

“The city had a history of making, and it has a future of making,” says Merrill. “It’s making different types of things, maybe, but [making] really is ingrained in Claremont.”

Current Issue - July 2024

Current Issue - July 2024