What a difference a decade makes. Ten years ago, in the spring and summer of 2013, the idea of expanding Medicaid to provide government-funded health insurance for an additional 50,000 NH residents was on life support.

Today, as the current session of the state Legislature careens toward a June 30 conclusion, expanded Medicaid is about to become a permanent part of the state’s health-care ecosystem. Gov. Chris Sununu supports it as does the Republican-led state Senate, which voted 24-0 in favor.

Such an outcome was far from certain at the advent of Obamacare in 2013. Republicans in the NH Legislature voted to block the state from participating in the federally funded expansion of the health insurance program for low-income Americans, a cornerstone of the Affordable Care Act.

Such an outcome was far from certain at the advent of Obamacare in 2013. Republicans in the NH Legislature voted to block the state from participating in the federally funded expansion of the health insurance program for low-income Americans, a cornerstone of the Affordable Care Act.

At the time, about 137,000 Granite Staters were eligible for Medicaid under stringent requirements, including very low income and at least one other exacerbating condition, like having a disability or being a single mother. Under expanded Medicaid, low income would be the only requirement, with slightly higher limits resulting in many more eligible participants.

While the state was on the hook for 50% of the costs for traditional Medicaid, the federal government, through the ACA, at first pledged to cover 100% of the costs for the expanded population, declining to 90% by 2020. Democratic-led states jumped at the offer, while most Republican-led states balked. Among the leaders of the opposition in NH was then-Senate Majority Leader Jeb Bradley. “I’m very skeptical that we should expand Medicaid and I get more skeptical every day as other aspects of Obamacare can’t seem to get implemented,” he said at the time.

No More Sunset Provision

Fast-forward to the spring of this year and Bradley, now Senate President, is testifying before both Senate and House committees in favor of permanent expansion, with no sunset provisions. In an op-ed published in statewide media in March he offered this unqualified endorsement:

“Since 2014, New Hampshire has charted its own path in providing expanded access to the Medicaid program for low-income families while protecting New Hampshire taxpayers. This Granite State approach has helped make health care affordable for thousands of people, lowered health-insurance costs, and reduced uncompensated care costs at New Hampshire hospitals, which is a hidden tax passed on to employers and individuals with private insurance. After nine years, Medicaid Expansion has proven to be a success and should continue.”

New Hampshire is certainly not alone in the turnaround on expanded Medicaid. When Medicaid expansion first took effect in 2014, it was only available in 26 states and DC. Since North Carolina approved expansion in March, only 10 states are now holdouts.

New Hampshire is certainly not alone in the turnaround on expanded Medicaid. When Medicaid expansion first took effect in 2014, it was only available in 26 states and DC. Since North Carolina approved expansion in March, only 10 states are now holdouts.

“I would say the thing that is causing this to be better received than it was 10 years ago is the fact that we have the numbers and data to support the statement that the program works,” says Alex Walker, president and CEO of Catholic Medical Center in Manchester. “There’s is no question about it. When you look at the number of uninsured patients coming through our facilities today compared to then, it’s a staggering difference.”

The NH Hospital Association reports that costs associated with treating uninsured patients averaged $157 million from 2012 to 2014 but fell to $65 million from 2017 to 2019, after Medicaid Expansion’s implementation and before the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The drop in uninsured patients across the state is about 59%,” says Walker. “Here at CMC, a more urban hospital, that number has dropped even more. We’ve seen about a 70% decline between 2014 and 2022 on an inpatient basis.”

Many Close Calls

There were many points over the past 10 years when the program could have been terminated, the most precipitous coming in 2016 when Republicans wanted to impose a work requirement. The House was deadlocked 181-181, before then-Speaker Shawn Jasper, a Republican, cast a tie-breaking vote to ensure the program would continue even if courts struck down the work requirement, which they did.

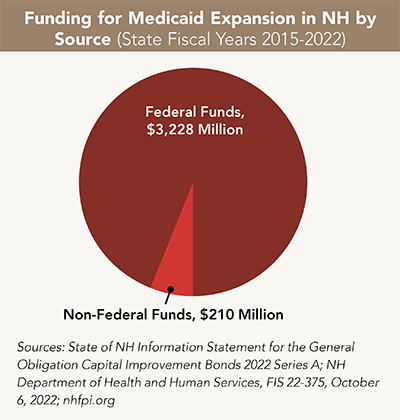

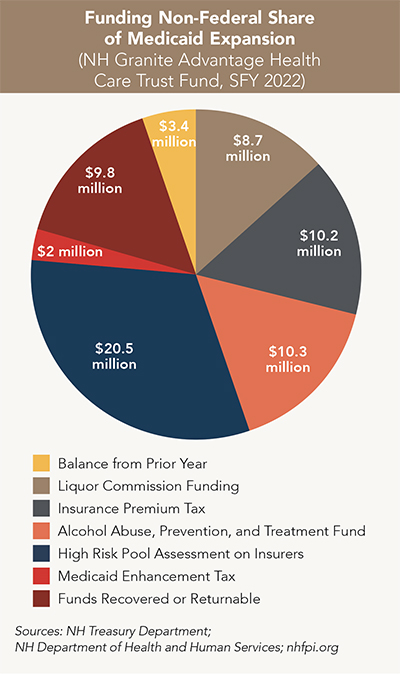

The program brought about $3.22 billion in federal money for health care into NH between its launch in August 2014 and June 2022, with about $210 million invested to cover the state share, according to an analysis published in January by the NH Fiscal Policy Institute (NHFPI). The most significant sources of funding for the state share are an assessment on insurers, transfers from the Alcohol Abuse Prevention and Treatment Fund, and an Insurance Premium Tax.

The program brought about $3.22 billion in federal money for health care into NH between its launch in August 2014 and June 2022, with about $210 million invested to cover the state share, according to an analysis published in January by the NH Fiscal Policy Institute (NHFPI). The most significant sources of funding for the state share are an assessment on insurers, transfers from the Alcohol Abuse Prevention and Treatment Fund, and an Insurance Premium Tax.

“Since the Medicaid Expansion program began in New Hampshire, approximately 93.9% of funding has come from the federal government. This percentage is higher than 90% because the federal government paid for the entire cost of the program in calendar years 2014 to 2016, and the match rate declined incrementally to 90% between 2017 and 2020. The 90% match is set by [federal] statute to continue permanently,” according to the NHFPI study.

While the additional money is a welcome boost to the bottom line for many NH hospitals, Medicaid reimbursement rates are a fraction of actual hospital costs. However, hospital executives will be the first to say that some money is better than no money. “For any Medicaid patient, we get paid well below cost of care, so its advantageous for us to have fewer Medicaid patients. But the alternative is totally free care or hospital-supported charity care,” says Dan Gross, CFO at Cheshire Medical Center in Keene. “Medicaid is a bit of a drop in the bucket in terms of real dollars. But in terms of the feeling of shared responsibility, I think it’s really important.”

Patients are the Big Winners

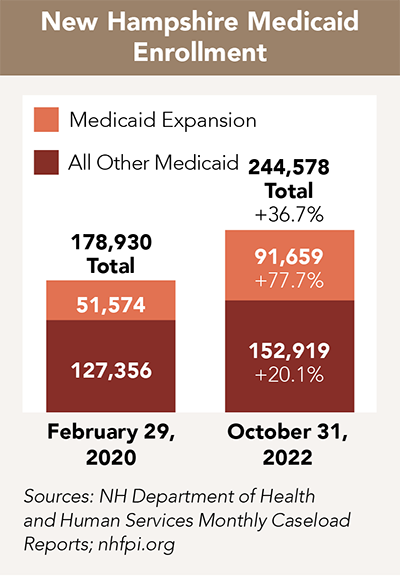

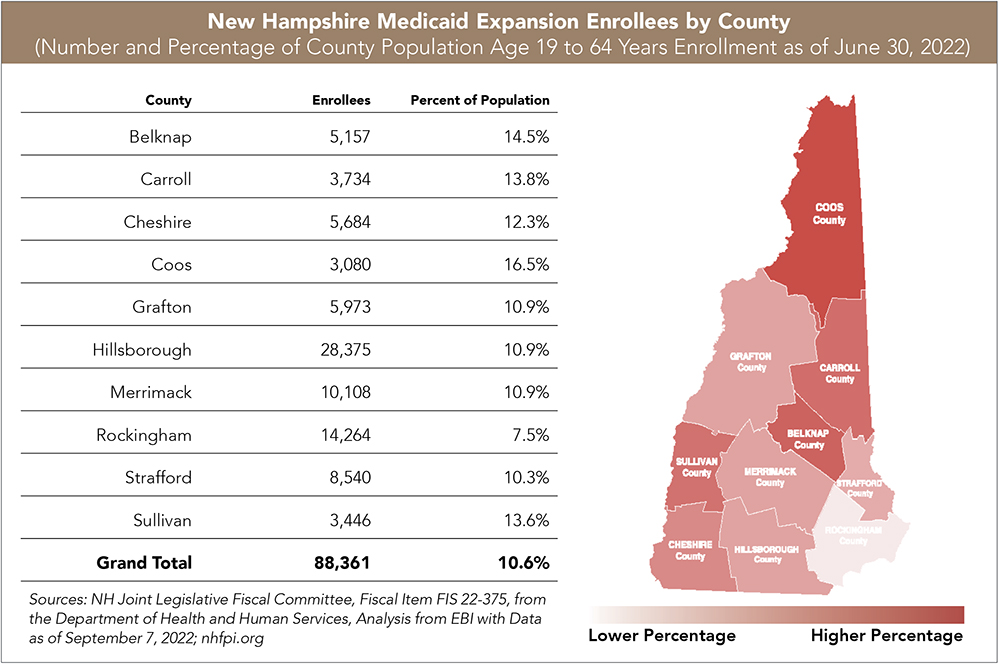

The most significant impact has been felt by the 219,000 Granite Staters who’ve been able to access care since Medicaid expansion became law. There are currently about 95,000 NH adults served, although that is expected to decline to close to 60,000 as COVID-era provisions for extended eligibility expire. They are disproportionately younger adults, living in the rural or less-populated parts of the state, who rotate in and out of the program as they work seasonal jobs in hospitality and tourism, according to the NHFPI.

“Most importantly its provided critical health care coverage for patients who were formally uninsured and couldn’t access primary preventative care,” says Steve Ahnen, president and CEO at the NH Hospital Association. “They often ended up in emergency rooms to get care when conditions became a crisis. Now those individuals have access to health insurance and are able to get care when and where they need it.”

Opponents of permanent expansion, like Greg Moore with Americans for Prosperity, worry that the federal government could someday reduce its share and that the program is keeping able-bodied workers from entering the workforce. This, he says, would increase their income and make them ineligible for

the program.

Former state Sen. Tom Sherman took issue with that assessment in his April testimony before the House Health and Human Services Committee. “It actually gets them back to work and off public assistance,” he said.

Current Issue - May 2024

Current Issue - May 2024