Six months into the pandemic, the coronavirus sapped a health care system already stretched by spiraling costs and a scarcity of professionals, particularly in remote areas. The American Hospital Association estimates that between March 1 and June 30, America’s hospitals and health systems incurred an average loss of $50.7 billion per month.

But not every facet of the industry is reporting bleak economic consequences. The same delay in routine medical procedures, screenings and high-priced elective procedures, such as hip and knee replacements, that hit hospitals hard resulted in substantial savings for health insurers that continue to collect premiums but pay out fewer claims.

For hospitals, the loss of revenue from those delayed services is a significant blow. Small hospitals, like the ones in NH, would typically recover from such shortfalls by cross-subsidizing services, says Reagan Baughman, associate professor of economics at the Paul College of Business & Economics at the University of NH. Fees from cardiac, neurosurgery and other outpatient procedures offset the monies hospitals forgo providing trauma care. Along comes the global pandemic and this strategy is turned on its head by a temporary shutdown of cash-positive operations in order to gear up for a surge of coronavirus-infected patients.

“That has become a definite issue for the financial health of hospitals and the reason they’ve needed stimulus money and may need more financial support,” says Baughman.

In response to the pandemic, Congress outlaid tens of billions of dollars to hospitals and health care providers as part of its $2 trillion to $3 trillion stimulus bill, the largest of its kind in modern history.

However, health insurance companies are seeing earnings rise. UnitedHealth Group, the parent company of UnitedHealthcare and the largest private health insurer in the U.S., announced a sharp uptick in its second quarter earnings, more than $1.5 billion than the same quarter from the previous year.

National health insurer Anthem, which operates Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield in NH, doubled its profits to $2.3 billion in the second quarter ending June 30 compared to $1.1 billion for the same period in 2019, according to its most recent earnings report. Revenue rose 15% to $29 billion. Anthem, which serves 459,000 members in NH, doesn’t segment earnings by state.

Lisa Guertin, president of Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield in NH, says since savings surpassed coronavirus-related treatment costs, Anthem-NH accelerated the rebates afforded under the ACA, and for its fully insured customers offered a 15% one-month premium credit for medical; 50% for dental.

To help consumers prevail through the pandemic, or perhaps because of pressure from regulators, Anthem eased its underwriting policies to allow laid-off or furloughed workers to maintain their coverage. “That’s not an industry standard thing to do,” says Guertin. “Relaxing that requirement isn’t going to harm our business.” On the provider front, Anthem loosened administrative requirements, such as the need for prior authorizations.

Gerri Vaughan, president of Tufts Health Freedom Plan, which serves around 40,000 members and is a joint venture between Tufts Health Plan and five NH hospitals, says claims costs have fallen, but any long-term predictions on how that will affect the bottom line are premature.

“It’s too early to determine the overall impact on an annual basis,” she says.

Tufts Health Plan’s business is split evenly between self-funded employers and fully insured. Small employer groups, under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), receive rebates if the plan does not spend at least 80% of the premiums on health care services over a 3-year annual average.

“Any savings that is accrued is going to make its way back to either the employer or directly to the member,” says Vaughan.

Digital Insurance Tools

The pandemic accelerated the development of digital insurance tools and coverage for telehealth options. In March, Gov. Chris Sununu issued an emergency order mandating insurers cover telemedicine services. On July 12, the state enacted HB 1623, expanding telemedicine to include audio-only phones and requiring health care providers to be reimbursed at the same rate as in-person visits.

“Telehealth is now really the new way in which people are accessing health care,” says Vaughan. Like the grand experiment of remote work, telemedicine is proving the silver bullet in a COVID-19 ravaged environment. As with work-at-home scenarios, it’s been transformative and will likely serve as the default paradigm for certain types of care.

Telemedicine offers a lower cost alternative to the burdens of face-to-face, says Guertin, and it’s easier to access. Anthem’s tallies bolster that prediction. In March, telemedicine visits were 33 times higher than at the beginning of the year; by April, they were four times those of March.

The pandemic fast-tracked the acceptance of telemedicine by about a decade, says Guertin. It also propelled Anthem to develop a suite of data and artificial intelligence software tools to help business leaders plan for re-openings while mitigating exposure to the virus.

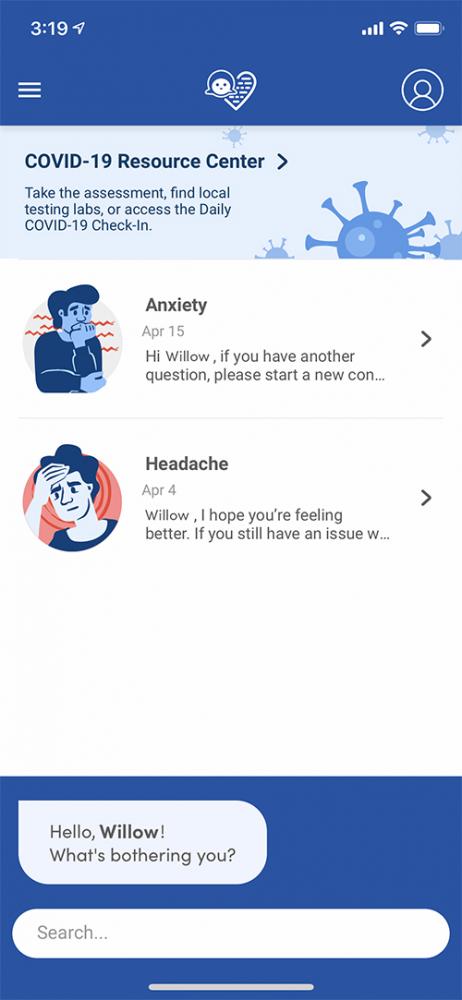

Guertin says insurers have a role to play in safeguarding consumers against the novel coronavirus. Using the Anthem-developed “Sydney Care” app (pictured), customers get health and wellness reminders, can assess symptoms for coronavirus and find COVID-19 testing locations near where they live.

Guertin says insurers have a role to play in safeguarding consumers against the novel coronavirus. Using the Anthem-developed “Sydney Care” app (pictured), customers get health and wellness reminders, can assess symptoms for coronavirus and find COVID-19 testing locations near where they live.

Promoting digital tools helps members feel connected in an often-isolated environment, says Vaughan. Telemedicine also leverages access to behavioral health. “It ensures that if people are feeling lonely, remote or [experiencing] other impacts of COVID-19, we have benefits available to them, so collectively, we’re all weathering this storm together.”

There is hope but no timeline for the arrival of a vaccine. One day people will work again in offices, go out to movies and shop in stores. To ensure the demand for telemedicine doesn’t fade post-pandemic, members of the U.S. House Telehealth Caucus introduced the bipartisan Protecting Access to Post-COVID-19 Telehealth Act to loosen restrictions on telemedicine coverage.

No one is suggesting all medical visits can occur virtually. Avoiding in-person consults may hinder critical diagnoses. This was the fear in the first few weeks of the pandemic when emergency department visits declined 42%, including visits for life-threatening conditions such as heart attacks, strokes and high blood sugar, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Vaughan says that Tufts Health Freedom Plan encourages its members to schedule mammograms, colonoscopies, children’s immunizations and other routine screenings. Getting preventive care is equally important as wearing masks and social distancing.

Reevaluating the System

In a typical recession, the physical health of non-elderly adults may improve, says Baughman. However, this recession is “unchartered territory.” A health crisis, as opposed to mortgage lending to subprime borrowers, triggered this economic contraction. And while auto accidents are lower because bars are closed and fewer people are traveling, the economic fate of the health care system is under duress. “I think the outlook is uncertain,” Vaughan says.

Unlike other developed countries with a nationalized health system, the United States lacks a coordinated effort from governments and private industries, says David Turcotte, a research professor at UMass-Lowell. Without a centralized system, he says agencies can’t easily shift resources, accomplish contact tracing and provide protective and testing equipment where they’re needed.

Reforming the health care system is not likely to happen under the current White House administration, Turcotte says. But with massive unemployment, people risk losing their health insurance. A survey from the Commonwealth Fund reports of those who lost a job or were furloughed in the U.S. or had a spouse or partner who lost a job, 41% depended on that job for coverage.

Baughman of UNH suggests that an unemployment crisis unparalleled since the 1930s will compel people to evaluate the country’s fragmented health insurance system. The system provides high-paid workers with better benefits, and low-wage employees, often essential workers, with little or no coverage. She also says there’s no simple fix to break from employer-based insurance due to tax incentives.

Providing a safety net for people who lose coverage was the impetus behind the ACA, says Turcotte. If individuals become unemployed, change employers or go out on their own, under the ACA they don’t have to worry about waiting periods or pre-existing conditions.

“The ACA has the potential to cover a large share of people who lose job-based health insurance,” writes Larry Levitt, an official with the Kaiser Family Foundation, in the May 28 JAMA Health Forum. “But this crisis may also expose weaknesses in the law’s design, how it has been implemented and how it has been weakened by the Trump administration.”

Pundits have long debated the viability of employer-based health care. About 60% of Americans view health coverage as a national responsibility and a third of those favor a single payer system, according to a 2018 national survey by Pew

Research Center.

Adjusting Coverage for COVID

On March 12, NH’s Insurance Department mandated health insurers to cover testing for COVID-19, including a doctor’s visit to get the test at no cost, and to promote early detection and access to prevention, treatment and recovery services.

“If people are getting the care that they need, we may be able to mitigate overall costs to the health insurance markets,” Insurance Commissioner Chris Nicolopoulos stated in March.

For those who don’t have insurance, the state of NH and ConvenientMD have reached an agreement for free testing at their locations.

As the pandemic continues, health insurance companies are removing barriers to test and treat the coronavirus without cost-sharing and co-payments. How these stipulations will economically affect the second half of the year for insurers is a wild card.