The pandemic gave millions a chance to do their work at home, or wherever else they chose, rather than at an office. They liked it, and now that health concerns have returned to 2019 levels, many of those workers have told their boss that they don’t plan to come back into the office every day.

The pandemic gave millions a chance to do their work at home, or wherever else they chose, rather than at an office. They liked it, and now that health concerns have returned to 2019 levels, many of those workers have told their boss that they don’t plan to come back into the office every day.

Working remotely is hardly new and long preceded the pandemic. But the stay-at-home orders revealed just how many jobs could be done anywhere there’s internet access. That, in turn, revealed something else: Remote work, while often preferred by workers, comes with health risks.

Those risks can be environmental, as the furniture and air quality at a person’s home might not be up to the same standards at their company’s office. They can be behavioral, as people who work from home might be less likely to get as much exercise or might be more likely to raid their pantry when no one’s looking.

Employers are finding ways to engage their remote workers in healthier eating and activity, whether it is virtual lunch-and-learn sessions about better eating habits or offering access to online fitness instruction such as yoga or holding walking challenges by sending employees pedometers and offering prizes to those with the most steps.

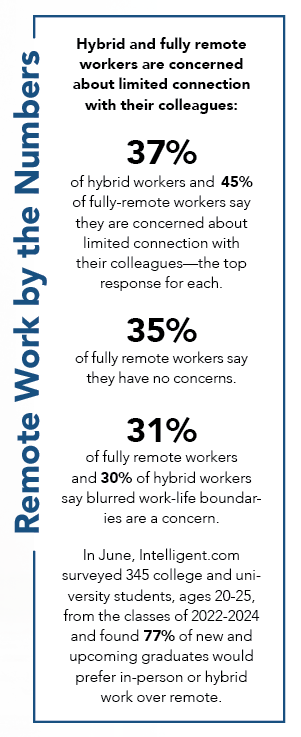

One of the biggest health risks facing remote employees is mental health issues due to isolation, depression and anxiety, which might not be as apparent through video meetings as in a face-to-face interaction.

According to a March article published by the Society for Human Resource Management, analyses by the Integrated Benefits Institute shows “fully remote (40%) and hybrid work (38%) are associated with an increased likelihood of anxiety and depression symptoms compared to in-person work (35%).”

The Steady Uptick of Remote Work

As it appears remote work is not going away, employers may want to find ways to mitigate these health risks. “There’s a certain percentage that have always been doing this,” says Annette Nielsen, an economist for NH Employment Security, about remote work. Indeed, the statistics she analyzes, which come from quarterly census data collected by the Wages, Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau, show that the number of workers in NH who didn’t have an assigned location for their work was already steadily rising, from 2% in 2006 to 3.4% in 2019. But the pandemic hastened the trend and 2022 figures show a more considerable jump to 6.2%.

“That has been quite a rise,” Nielsen says. In absolute figures, that translates to around 41,000 workers in NH, so, “still not huge,” in Nielsen’s view, but a trend worth watching.

It’s also a trend that’s challenging for economists to accurately measure. The above statistics were for workers who didn’t have a fixed address assigned to their labor. That means that it likely didn’t capture the many workers who are now on a hybrid schedule, who might only go into the office one or two days per week.

Shining a light on that gap is a survey conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics in summer 2022, which found that 19.9% of NH establishments reported that their employees were teleworking at least some of the time. Only a few reporting districts—Minnesota, Massachusetts, and Washington D.C.—were higher.

Nielsen says it makes sense that NH would stand out on that list as data demonstrates that the sectors that tend to have a high percentage of remote workers—wholesale trade, professional and technical services, finance and insurance, and information—are prevalent in NH.

Positives and Negatives

While those who can work remotely often speak positively about their experience, they also report some downsides. Dr. Liu Yang and her colleagues in the NH Occupational Health Surveillance Program at the University of NH’s Institute on Disability recently conducted a study to see how the pandemic affected small businesses in NH. The study involved more than 30 small businesses and collected responses from both workers and employers.

The study found both positive and negative outcomes. On the positive side, customers and even public institutions embraced the convenience and accessibility of video meeting capabilities and those meetings have continued even after some have returned to the office. Employers found that their workers could be just as productive, and so have largely continued to make remote work available for their workers, about which one respondent said, “I think that’s given a lot of us a sense

of well-being.”

The negative side that the study revealed a sense of disconnection. Video meetings, while convenient, don’t offer the same richness of communication that in-person exchanges provide. Respondents said they realized, in their absence, the value of seemingly trivial connections with co-workers, such as small talk before a meeting starts, or catching up with someone who happens to be passing their desk.

“It’s not that there’s something wrong with the technology, but it doesn’t feel as comfortable to have water cooler conversations or drop-in consultations meetings when you have to log into a Zoom account or call someone versus stopping by someone’s office,” one respondent said.

From a human psyche standpoint, NAMI-NH Executive Director Susan Stearns, says, “We’re not meant to navigate the world alone.” At the same time, she points out, “There are real advantages to remote work. No question. And the reality is, some people can tolerate being alone longer than others, but for a lot of adults, work is our social interaction.”

Stearns cites a disadvantage of remote work in terms of those “water cooler moments,” where connections to coworkers happen. “For us, it’s the kitchen. You can’t replace those conversations that people have at lunchtime or first thing in the morning when people get their coffee. Sometimes our best ideas happen at those times.”

Balance is important, Stearns says. “As humans, we’re meant to be in community,” she says. “And with that said, we’re a statewide organization. Remote tools also allow us to stay connected and that’s a bonus.”

Managing the New Normal

None of Yang’s findings would be surprising to Katharine Offinger, who manages a team of 20 for a strategic communications firm based in Manhattan. Offinger used to work out of the New York City office, until she and her family left in the pandemic and set down roots in the rural town of Sandwich, NH. Since 2020, she’s been managing her team remotely, even after most returned to a hybrid schedule earlier this year.

“The people I manage today, some are still remote, most of them are based in New York. Two days a week they’re in the office, the rest of the week they are remote,” Offinger says. “People say they love it and will always say that they love it.”

Yet, she says she has also seen negative outcomes that cropped up during remote working. Those who rode out the pandemic in the city were confined to their apartment for significant periods of time, which made exercise hard to come by.

“I know I saw it in myself, too,” Offinger says. “It took a lot of effort for me. I had some days when my step count was in the hundreds.”

But the more concerning outcomes she saw were related to mental health. “I think people who have gone remote and stayed remote, are stressed out about not being promoted or being left out because they’re not in the office,” Offinger says.

Then there’s the way that remote communication changed the nature of how her team members related to clients. “It’s hard to put a finger on it, there’s this weird negative vibe,” Offinger says. “There’s an idea that our clients see us as squares in a box, instead of humans, and it increases this negative stress, animosity… There’s a noticeable lack of humanity, and that manifests internally.”

In the office, she says, her colleagues wouldn’t walk around “whispering smack about other people,” but on the work-focused social media application Slack, it’s easy for people to start a side chat between two or three workers.

These negative outcomes are despite a “wonderful culture” that her company has created, she says. “It’s really tight knit. It’s not because the culture has changed, it’s because we’re not shaking hands with each other every day and seeing each other every day.”

Offinger’s company has responded by providing employees with subscriptions for mindfulness apps, and mental health services. Offinger has found there are things she can do as a manager to help mitigate some of these concerns, particularly those around feelings of isolation and mental health.

“I try to make an effort to go down once a month, whether I need to or not. I try to see everyone in the office, do the same kind of things we used to do prior,” she says, such as going out with her team for happy hour or ice cream, “trying to maximize the little amount of time we have together.”

Team members create playlists to share their favorite new music with one another, they talk about what shows they’re watching, or how their weekend plans are shaping up. “These moments, these 15-minute moments where we’re just humans,” Offinger says, can restore a sense of connection with the team, and can counteract any dehumanizing treatment they’ve received from clients.

It is now about creating watercooler moments “because we don’t have a water cooler anymore,” Offinger says. “Inventing reasons for us to chat, not as co-workers but as humans, has been really important for destressing.”

Staff writer Scott Merrill contributed to the reporting in this article.