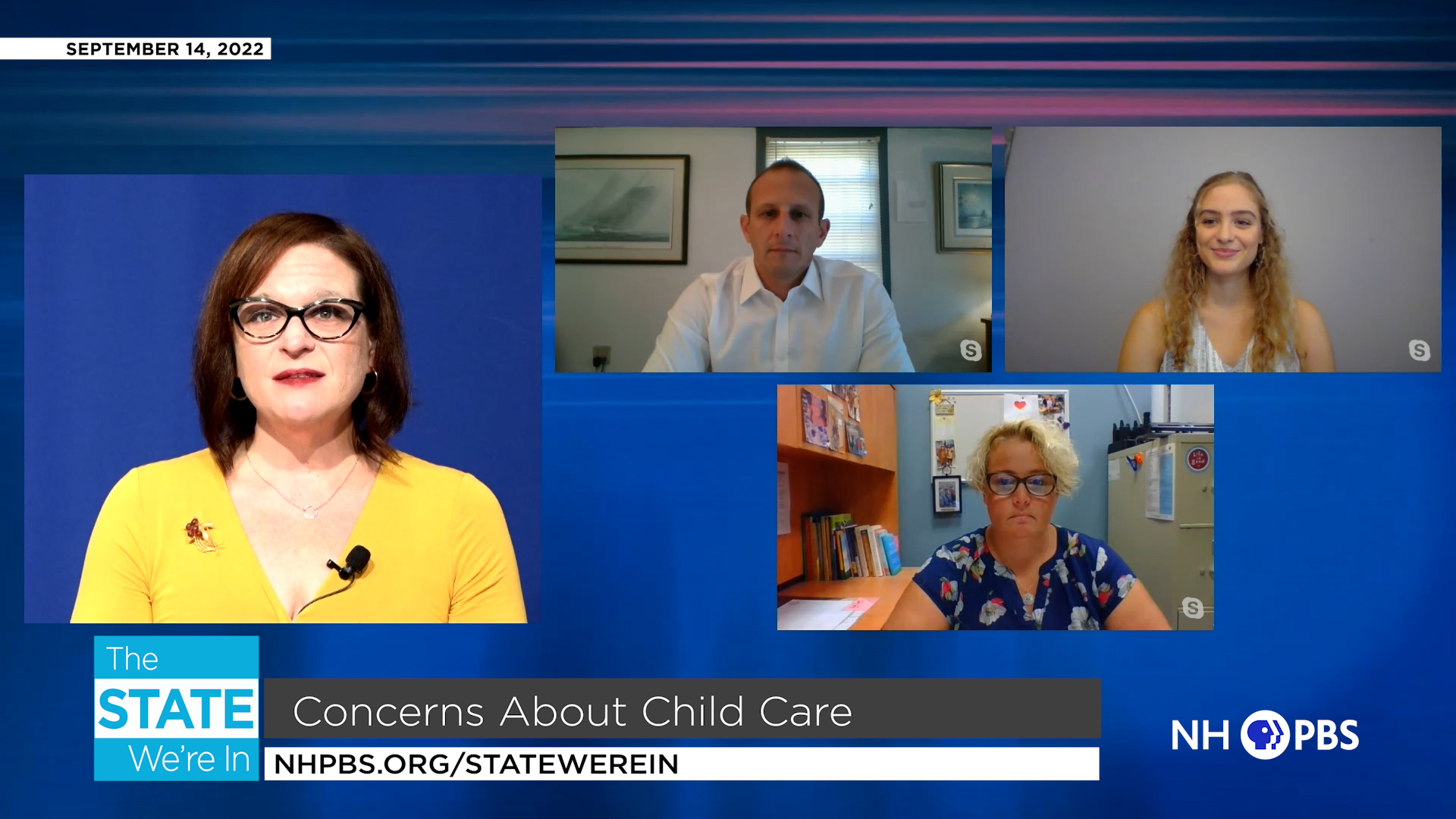

From Granite State News Collaborative and NH PBS The State We’re In: Concerns About Child Care

Host Melanie Plenda discusses childcare and the critical need it serves not just for parents, but the community at large in New Hampshire, and the stresses parents experience in trying to find affordable, safe options for their children. Joining her are reporter Rhianwen Watkins, Shannon Tremblay, the director of Little Blessings Child Care Center in Portsmouth, and parent Colby Gamester.

Click here to watch the full interview on NH PBS's The State We're In

GSNC/NHPBS

The State We’re In program Concerns About Child Care

Host Melanie Plenda discusses childcare and the critical need it serves not just for parents, but the community at large in New Hampshire, and the stresses parents experience in trying to find affordable, safe options for their children. Joining her are reporter Rhianwen Watkins, Shannon Tremblay, the director of Little Blessings Child Care Center in Portsmouth, and parent Colby Gamester.

This content has been edited for length and clarity. Watch the full interview on NH PBS's The State We’re In.

Melanie Plenda: Rhi, you interned over the summer with the Granite State News Collaborative at a partner newsroom, Seacoast online, where you did a story about childcare in New Hampshire. Can you walk us through what your findings were and tell us about that cycle you found?

Rhianwen Watkins: What I found in speaking to a lot of different people, childcare centers, and parents was that it really is this cyclical issue that has a lot of different moving parts. I think it all begins with childcare centers facing worker shortages. That's because these workers are seeking out jobs that are higher paying. This in turn creates the wait list issue because childcare centers have this legal child to teacher ratio that they have to adhere to. If they don't have the personnel to meet these ratios they have to sometimes operate at say 50% capacity, hence creating wait lists that are sometimes two, three, even four years long at some places. That means that families are having to find alternatives to childcare, sometimes in the form of having a grandparent watch the kids, or it could be a nanny. Sometimes people have even started opening up their houses as these at home childcare centers.

The issue with that is a lot of these places are not licensed. They don't have the same qualifications that other childcare centers have, but that's a separate issue. Ultimately parents are left having to find alternatives. The other side of the cycle is that childcare centers have begun rightfully raising their prices so that they can pay their workers a livable wage, keep their workers, bring in more workers so that they can operate at full capacity. But again, this creates the issue that a lot of families can't afford childcare as these prices rise and are then again left having to find alternatives. It really is this vicious cycle. I interviewed the director and owner of Live and Learn childcare center in Lee, and I think she really worded it so well. She said the working family can't pay anymore, but the early childhood teacher can't work for any less. When it comes down to it, the root issue of it all is that there just isn't enough funding in childcare. If there was that funding, all of this wouldn't be an issue.

Melanie Plenda: Shannon, you've been in childcare and early education for 15 years. How long have these issues been a problem?

Shannon Tremblay: The early childhood field has always found itself struggling a little bit, having to prove ourselves in the professional field. We're not babysitters, a lot of us have degrees in either early childhood or child development. The system was already broken before the pandemic. It was already at a standstill and now the pandemic has just exacerbated that problem. The low wages have really turned people away from the field. In the past, high school counselors had told people to not go into early childhood, go into teaching because you'll make more money, you'll have benefits, you'll have pensions, which none of us have. But the fact is, the pandemic has really put a light on the fact that childcare is essential to all other businesses. If there is not childcare, then other people can't work, which means that those businesses will not have their own workforce.

Melanie Plenda: What's the situation like where you work at Little Blessings?

Shannon Tremblay: We're doing pretty good here at Little Blessings. We've been able to take some grant money that has come in through the state and that has been able to keep the doors open. However, we're running at 50% capacity and not making enough money to cover anything else above and beyond wages. We've had to make some changes to our hours of operation, cutting those hours down an hour on each end because we haven't been able to staff it, which may seem like a small little step, but to families who need that extra hour of care that's huge. We've also had to cut back on expenses, taking away some of the extras that we were being able to offer to the kids and to the families. We've also had to close classrooms as well as ask parents sometimes to keep their kids home for the day, which has been really tough to have to do.

Melanie Plenda: Rhi, I imagine that sounds familiar to you based on your reporting. How are New Hampshire childcare centers doing generally?

Rhianwen Watkins: It's different across all of them. Going back to Live and Learn in Lee, the owner told me they have a four year wait list, which is crazy to me that it can span that many years. She said they just had a four year old that they let in wwho's been on the wait list since the child was in utero. When you think about the fact that kindergarten starts around age five, that's only one year that this child would be in the early childhood program and all of that other time is having to find alternatives. When I think about just how long some of the wait lists are, that really is something that stood out to me in the reporting.

Melanie Plenda:Colby, as a parent what have your experiences been like finding care? I understand you joined a wait list pretty early.

Colby Gamester: My experience is funny and interesting and lucky more than anything. For other parents and families back in 2016, the childcare environment was different. To what Shannon said, the problem has been around for a long time, but even when the problem was still surfacing, it was a different environment. When I close my eyes, I can feel that environment because centers were enrolling at or near capacity, there was robust staff.There was a lot of demand, there were a lot of families, a lot of activity. My brother had his two children at Little Blessings. He was on the board and I had friends that were seeking daycare, so I kind of knew this going into wanting children with my wife.

When she found out she was pregnant, we were able to determine very early on for some health reasons and confirm with the doctor that she was in fact pregnant. I remember the next day after that doctor's appointment, I called the then director and said my wife is six weeks pregnant, I'd like to put our baby on the wait list for the infant room some 13, 14 months later. She laughed and said, of course, and I said, listen, you're the only person we're telling right now. My brother doesn't know and won't know for many weeks, so she agreed to keep it hush. At that point, I would check in at three months later, six months later when our son was born and it worked out, we got on top of things really early because by the time my wife's maternity leave was over, our son had a spot.

When my two and a half year old was born, she was born two and a half months before COVID. By the time my wife's maternity leave ended, COVID had already hit. When we were ready to send her to school it, we were very lucky because siblings get a priority on the wait list. Because we already had my son there, she was bumped up on a priority placement on the wait list. The robust staff was thin; the center was maybe even less than 50% enrolled that early on in COVID.

Melanie Plenda: You guys had the foresight to sign your son up when he was still in utero, but what about those parents who want to move here? They get a new job here or new opportunity, and they were never on the wait list. Have you heard anything about that? I know that you're involved with the United Way and this topic has also come up there. Are those among some of the things that they've discussed?

Colby Gamester: I have conversations all the time with friends and colleagues of mine who have moved to the state. If someone says I'm pregnant, I ask have you called any daycare centers? How many wait lists are you on? I shared a story with Rhi during her reporting, and I know Shannon and I have talked about similar issues where parents aren't waiting too long. They're not being lazy. They're not sitting on their hands, but they just fall into an area where they call when they're six months pregnant or their son or daughter were just born thinking that they're staying on top of things only to learn of the year plus waits. Then they're on multiple wait lists and they're juggling grandparents and nanny care or babysitter care, or working from home and splitting time with their parents. But that's the worst situation you can possibly find yourself in; when you think you're on top of the ball, when you think you're planning, and you realize you couldn't have called any earlier and that the problem would've still persisted.

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.