It’s been tritely called the “shedemic” or the “shecession,” but the chilling reality is the pandemic disproportionately affected women economically. And women of color were particularly hard hit and more so than anyone else.

It’s been tritely called the “shedemic” or the “shecession,” but the chilling reality is the pandemic disproportionately affected women economically. And women of color were particularly hard hit and more so than anyone else.

Depending on which study you look at, the pandemic either halted progress on closing the gender wage gap, or there was a slight bit of progress. But, that “progress,” according to Payscale’s “The State of the Gender Pay Gap in 2021,” is the result of more women at the lowest end of the pay scale either losing their jobs or leaving them to care for their families and no longer showing up as part of the workforce.

The number of women working full-time fell by 5.9% between 2019 and 2020, according to the Institute of Women’s Policy Research, while women working in service occupations plummeted 18.8%. At the upper end of the pay scale, the number of women working in management, business and financial operations inched up 1.5% during the pandemic.

Job Losses

The pandemic highlighted a great divide between white collar workers who could work from home and blue collar workers who were deemed essential but often work at the lower end of the pay scale.

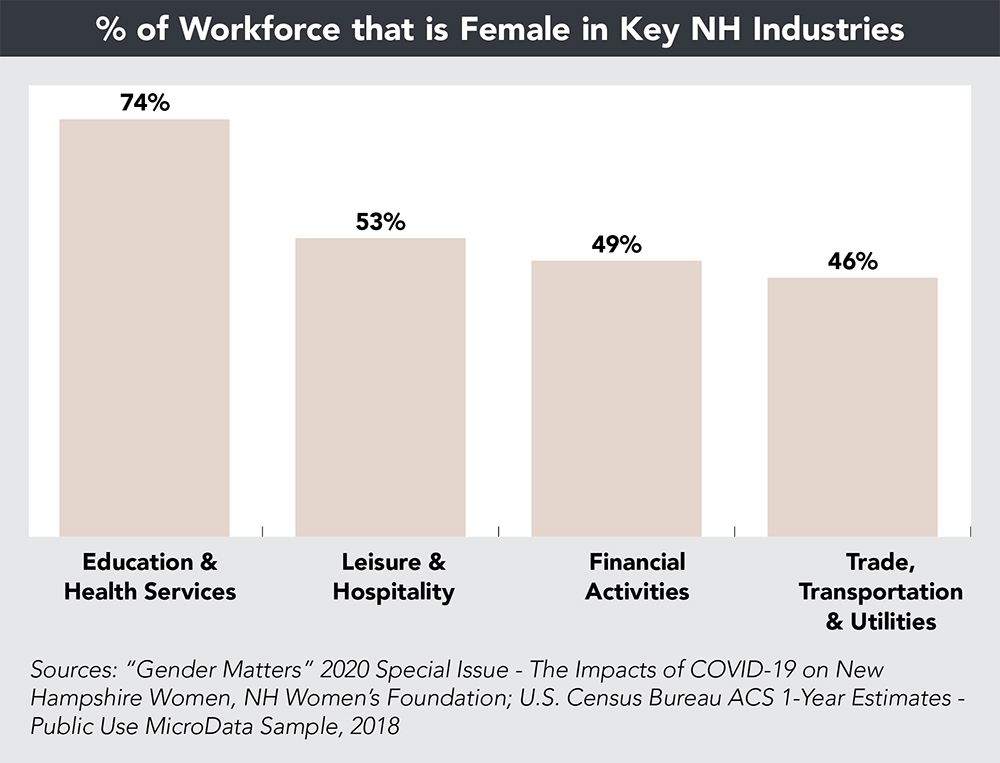

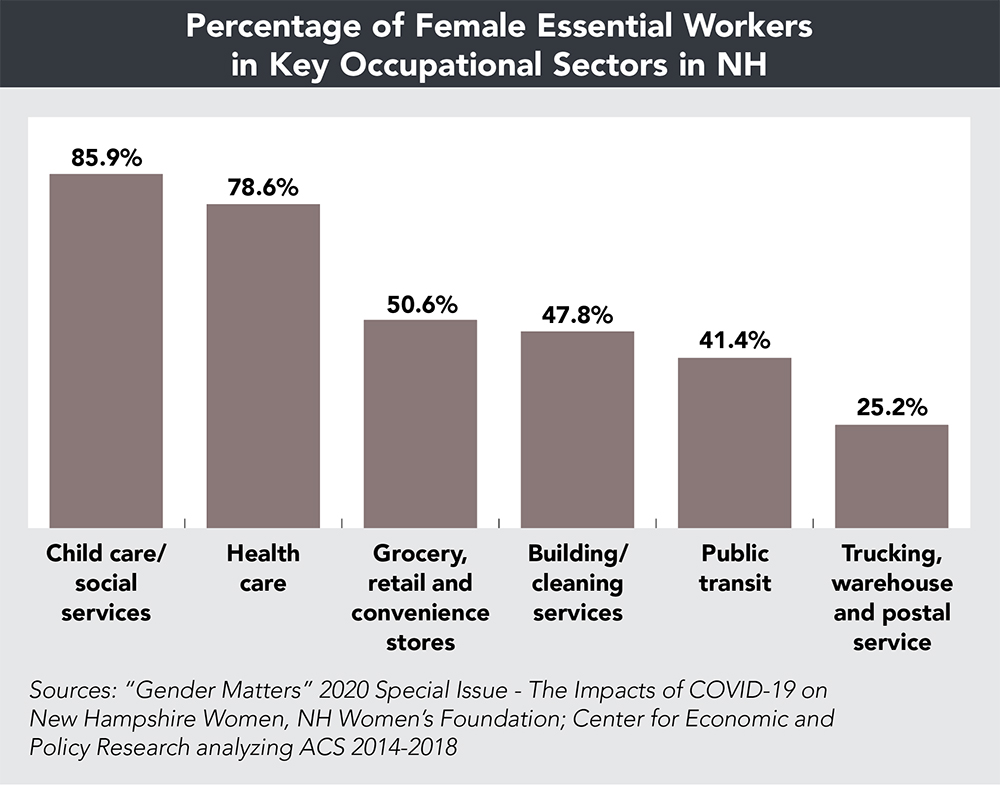

In NH, women make up 67.6% of essential workers, which includes child care and social services (85.9% of workers are women), health care (78.6% of jobs are held by women), and grocery, retail and convenience stores (50.6% of workers are women), per a 2020 report by the NH Women’s Foundation about the effects of the pandemic on women. (The foundation did not respond to several requests for interviews for this article.)

Women were also overrepresented in sectors that were particularly vulnerable to shutdowns early on such as retail and hospitality, which saw many employees furloughed or laid off. A February 2021 study from the Center for American Progress reports that women lost a net 5.4 million jobs nationally during the pandemic—nearly 1 million more than men.

That same report estimated that mothers leaving the labor force and reducing work hours due to caretaking responsibilities amounts to $64.5 billion annually in lost wages and economic activity.

“The hardest hit sectors tended to be ones that hired more women,” says Chandra Reber, director of the Center For Women & Enterprise NH-Women’s Business Center, which helps women start and grow businesses. Reber says she has seen an influx of women asking for assistance because they were laid off during the pandemic or had to leave their jobs to care for family.

Women of color were disproportionately affected by job losses. The Carsey School of Public Policy report shows Latina women had the highest jobless rates throughout the pandemic, peaking at 20.8% in April 2020. By June, the Carsey study goes on to say, that was down to 16.3% while the jobless rate for Black women was at 14.2% and white women had the lowest jobless rate throughout the period, with a rate of 10.1% in June 2020, according to the Carsey report.

At a time when NH employers struggle to fill jobs, part of the problem can be sidelined workers. “More than one in four women are contemplating what many would have considered unthinkable just six months ago: downshifting their careers or leaving the workforce completely,” states a report, “Women in the Workplace 2020,” which was released in September by McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.org. “This is an emergency for corporate America. Companies risk losing women in leadership—and future women leaders—and unwinding years of painstaking progress toward gender diversity.”

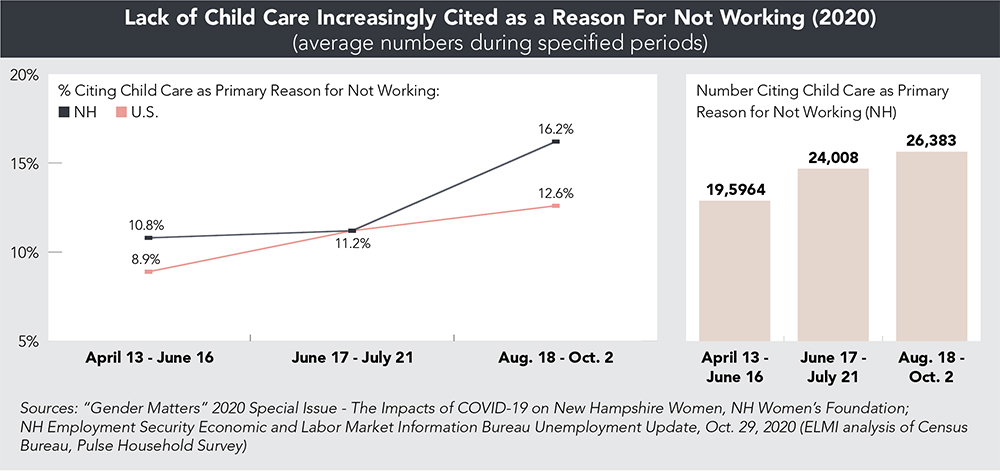

“Over the span of the pandemic and the onset of a new school year, the number of Granite State workers who are out of the labor force, citing child care as their primary reason for not working, had grown to 26,383 by October. Nearly all of these individuals were women,” reports the NH Women’s Foundation in a special COVID-19 study released in December 2020.

“Over the span of the pandemic and the onset of a new school year, the number of Granite State workers who are out of the labor force, citing child care as their primary reason for not working, had grown to 26,383 by October. Nearly all of these individuals were women,” reports the NH Women’s Foundation in a special COVID-19 study released in December 2020.

The Center for American Progress report estimated 4.5 million child care slots could be lost permanently due to the pandemic while a survey in December by Procare Solutions, which provides tech tools for the child care industry, showed about 25% of all child care providers closed because of the pandemic.

“Overall, there’s also the mental exhaustion. For many women, it has been added pressure of working a job or running a business, plus caring for children and being responsible for education,” Reber says, adding some were also caring for aging parents either affected by COVID or without access to adult daycare.

Reber points to President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion recovery plan as a possible solution as it includes funds for both the child care industry and for parents paying for child care. New Hampshire could receive $77.4 million to support child care. “It would be good if parents in any state can count on the same level of infrastructure when it comes to child care and adult dependent care,” Reber says.

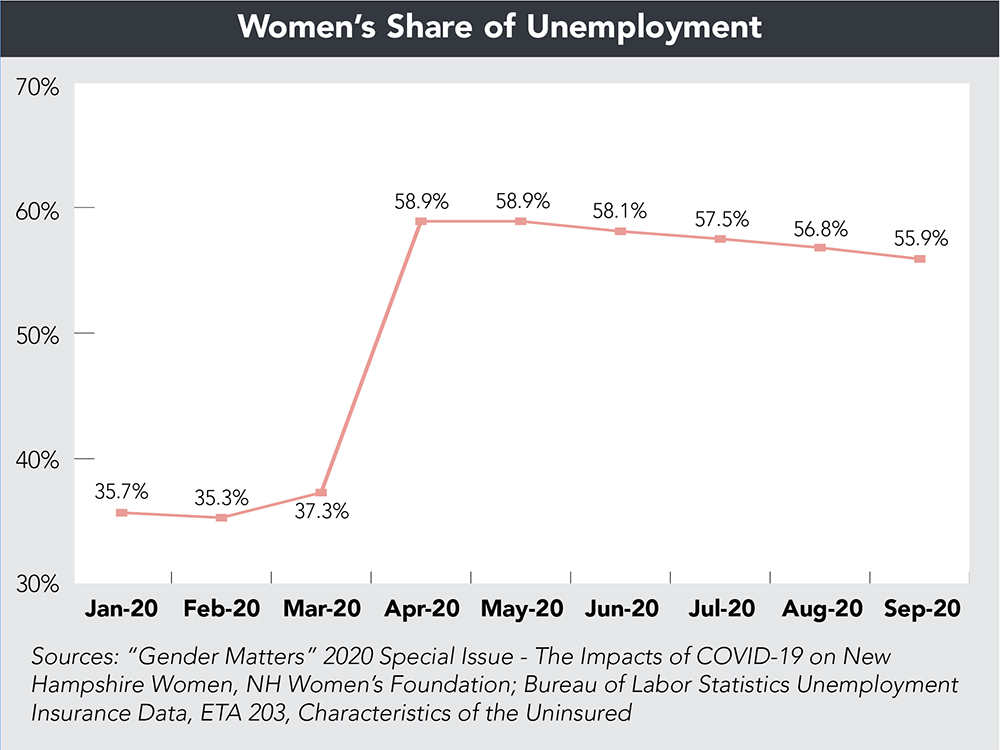

In February 2020, women were actually faring a bit better than men with an unemployment rate of 3.5% versus 4.25%, according to another 2020 Carsey School of Public Policy study. By April, though, the pandemic had flipped that trend with unemployment for women reaching 15.8%, while men were at 13.4%.

Women may achieve some parity as the economy recovers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics shows overall unemployment for women over 16 in March 2021 was 5.9% versus 6.2% for men ages 16 and older. And, NH’s recovery is happening quickly with overall unemployment hitting 3.2% in March—the fifth lowest in the country.

The Gender Pay Gap

In months, COVID-19 set back years of progress. According to the Brookings Institution, over the past 40 years, women accounted for 91% of income gains for middle-class families. About 2 million women have left the workforce during the pandemic to care for their families, and many are not returning, “The gender earnings gap is predicted to increase by 5 percentage points in this recession,” the White House reports.

In 2019, women earned 82 cents to every dollar earned by men, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, which is the narrowest gap ever achieved. And NH ranks 15th nationwide for having the highest gender pay gap with an 18% difference between men and women, per “The Gender Pay Gap Across the U.S. in 2021,” an analysis by Business.org. The average female salary in NH is $49,291 while the average male salary in NH is $60,406, according to that same report.

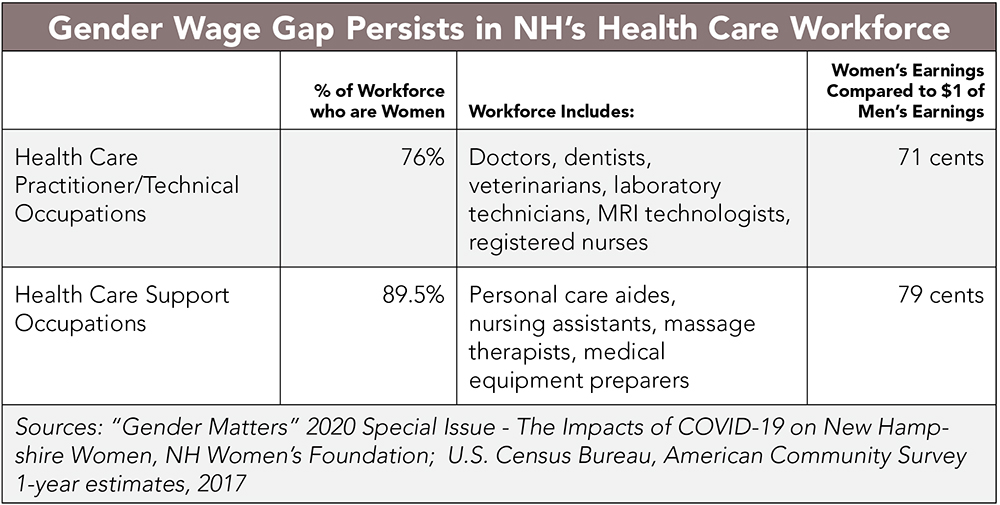

The pay gap exists across a number of sectors. Despite 87% of registered nurses being women, male nurses earned a median salary of $73,603 versus $68,509 earned by female nurses in 2019, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. And, while about 75% of cashiers, the lowest paid position in retail, are women, their median earnings, $22,032, are almost $2,600 less than their male counterparts. The gap is even more pronounced when moving higher up the economic ladder.

Women only make up 45% of first line retail sales supervisors, making median earnings of $36,432 versus $50,270 for men, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“During economic downturns and recessions, lost earnings due to the gender wage gap make women economically more vulnerable and add to financial hardship when women have less savings to cover emergencies or basic expenses,” states the NH Women’s Foundation in its COVID-19 report.

Reber says women returning to work face penalties for an employment gap. “It can make it harder to compete for jobs and command the same salary [than] if they had not left the workforce,” she says.

Access to Capital

Salaries aren’t the only challenge. Women running businesses also have less access to capital to grow their companies. And women-owned businesses accessed federal COVID-19 relief funds at a lower rate than their male counterparts, Reber says.

“Pre-pandemic, women have always had less access to capital. It was hovering around 4% of angel investing going to women,” says Reber, adding part of the reason for that is women tend to be more conservative and risk adverse when it comes to borrowing money. However, she notes, while women who are solo and “micropreneurs” contribute to the financial stability of their communities, investors tend to place a higher value on businesses with a higher growth potential, which often excludes the types of businesses women typically own.

A nationwide study released by Builders + Backers and Her Corner in April of this year examined how women-owned businesses fared in pursuing Paycheck Protection loans. It found while women business owners were not discriminated against during the application process, they were “passed over in several significant ways throughout the process that left them unable to take full advantage of the PPP.”

The study found nearly a quarter of the women-owned businesses surveyed never got their foot in the door to apply, extrapolating that “nationally, 3 million women-owned businesses that needed funding critical to stay open likely never even had a shot at a PPP loan.”

The study also showed that women who relied heavily on large national banks were less likely to obtain a PPP loan. And women-owned businesses asked for less funding and received less money than national averages.

The Center for Women & Enterprise worked with the U.S. Small Business Administration, the NH Small Business Development Center and SCORE to put information about loan and grant programs in front of its members, Reber says.

She adds the center saw an increase in calls during the early part of the pandemic from panicked business owners. As the pandemic progressed, callers sought advice on how to launch a business. Reber says courses about financial fundamentals, such as QuickBooks workshops, that were once hard to fill now have waiting lists.

Addressing Inequities

There is some hope, though. Reber says the pandemic highlighted many inequities in society and created a greater push for social justice. “There are an increasing number of companies and organizations looking at the social impact of their businesses both internally and externally,” she says, which includes examining hiring and pay practices and addressing the gender pay gap. “I do think there is more conversation and awareness,” Reber says, adding greater transparency is good for fairness.

The World Economic Forum identified four focus areas to accelerate closing the pay gap post-pandemic: reskilling women for re-employment in high growth sectors; enhancing work quality and pay standards across low paid essential jobs; enhancing social safety nets, especially child care; and setting targets for women in leadership positions in government and business.

“The crisis also represents an opportunity. If companies make significant investments in building a more flexible and

empathetic workplace—and there are signs that this is starting to happen—they can retain the employees most affected by today’s crises and nurture a culture in which women have equal opportunity to achieve their potential over the long term,” states the McKinsey report.

The report also notes that “less than a third of companies have adjusted their performance review criteria to account for the challenges created by the pandemic, and only about half have updated employees on their plans for performance reviews or their productivity expectations during COVID-19. That means many employees—especially parents and caregivers—are facing the choice between falling short of pre-pandemic expectations that may now be unrealistic, or pushing themselves to keep up an unsustainable pace.”

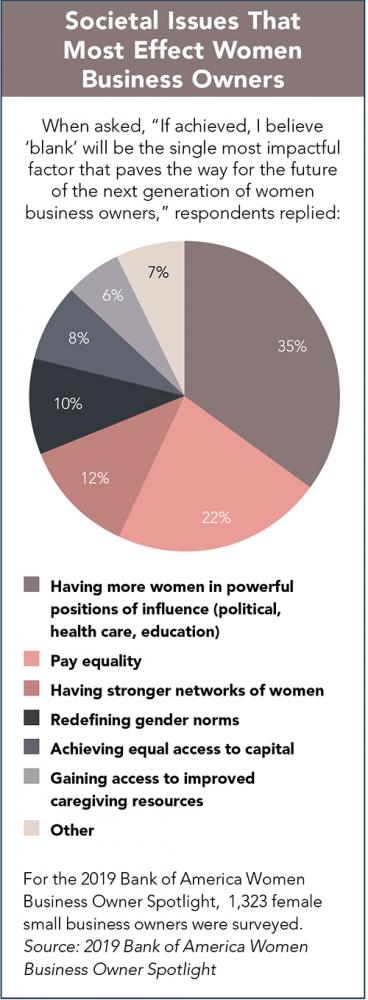

When Bank of America asked women business owners what factors would most influence the next generation of women business owners, they said having more women in powerful positions of influence (35%), pay equality (22%) and having stronger networks of women (12%). When asked what would be most helpful for women in business in the next five years, the top responses were: achieving work-life balance (95%), pay equality (92%) and improved access to capital (90%).

“Without intervention to address the disproportionate impact of COVID-19, women’s progress will continue to decline,” states the NH Women’s Foundation in its COVID-19 report. “Bold action now toward more equitable health, economic and caregiving systems will help reverse these declines in women’s health and financial security and more rapidly restore economic growth and family incomes.”

Reber says this is a societal issue that requires honest conversations about the systems and policies with inequity built into them. She adds companies need to uncover their own organizational and individual biases before developing new policies that address inequities.

Current Issue - April 2024

Current Issue - April 2024