Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of stories about how zoning affects NH’s communities and reinforces inequities. They are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. More stories in this series can be found online at BusinessNHmagazine.com and collaborativenh.org. A maze of invisible walls has divided Manchester since the 1920s, dictating what can be built where and, indirectly, where the city’s poorest residents can live. These walls, created by land use zoning laws, have helped segregate the city by income and more recently by race. Experts say that even though this kind of zoning is common, it is slowing efforts to fix some of the city’s most complex issues, including the housing shortage, persistent crime hotspots, and economic and racial segregation.

A maze of invisible walls has divided Manchester since the 1920s, dictating what can be built where and, indirectly, where the city’s poorest residents can live. These walls, created by land use zoning laws, have helped segregate the city by income and more recently by race. Experts say that even though this kind of zoning is common, it is slowing efforts to fix some of the city’s most complex issues, including the housing shortage, persistent crime hotspots, and economic and racial segregation.

Anthony Harris, 39, (pictured) is one of many Manchester residents whose path to finding housing has been redirected by these walls.

Two years ago, Harris and his girlfriend, Shaquan’DA Allen, unexpectedly found themselves on the hunt for a new apartment. “We were homeless,” he says, “and it was hard. Even though we had money, we didn’t have enough to get a place.”

After living out of their car for four or five months, Harris and Allen started saving to get their own apartment. Even though she ran her own hair salon on Granite Street, money was tight. It took a while to scrape the money together for first and last month’s rent on a two- or three-bedroom apartment. But when they thought they finally had enough, Allen started looking through the online listings.

Right away, the couple ran into problems. “So my Queen is sending me all of these apartments,” Harris says, referring to his girlfriend. Even though some of the listings looked promising, scrolling down to the details raised red flags. “I’m like, ‘Hey, look at the rent!’”

In the areas where they preferred to live, which was anywhere outside center city, Harris says that typical prices were more than $2,000 per month for a two- or three-bedroom apartment. This was far above their budget of $1,000 per month.

Even after starting the search again— this time just for one-bedrooms—they couldn’t make it work. The most affordable listing they saw was for $1,600 in some old mill buildings on the west side.

Harris and Allen looked all over. “When I say ‘all over’ I really mean it,” he says. But having found nothing they could afford, Allen and Harris started looking in the part of the city where they preferred not to live: center city, an area that in recent years has had relatively high rates of poverty and crime, and its neighborhoods are sometimes referred to as the tree streets. As a previously-incarcerated person, Harris says he preferred not to live there because he wanted to leave that life behind.

But everywhere the couple looked outside center city, they struck out. “I was even telling my Queen we can stretch it to $1,250, but then we got to sacrifice something to do it,” he says. “And it just still wasn’t good enough.”

Ultimately, the couple realized they didn’t have many choices. The best deal they could find was $650 per month to split a two-bedroom apartment with a roommate in center city, so that’s where they ended up.

“We couldn’t afford to go anywhere else,” Harris says, standing in his apartment near Pulaski Park, where he often sees the homeless sleep. “It’s like we’re forced to be here and just be grateful that you know, we do have a place when so many of us don’t.”

What Harris and Allen don’t understand, however, is why their choices were so limited in the first place, and why most of the affordable options were concentrated in center city.

With the housing crisis in Manchester and around the state receiving more attention in recent years, over the last six months the Granite State News Collaborative has looked at the history of housing policy in Manchester, NH’s largest city, to help answer that question.

Conversations with historians and housing experts, and an analysis of historical zoning data, show that the roots of today’s affordable housing shortage can be traced all the way back to the mid-1800s to discriminatory housing policies during the reign of the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company, and to exclusionary land use zoning laws since the 1930s.

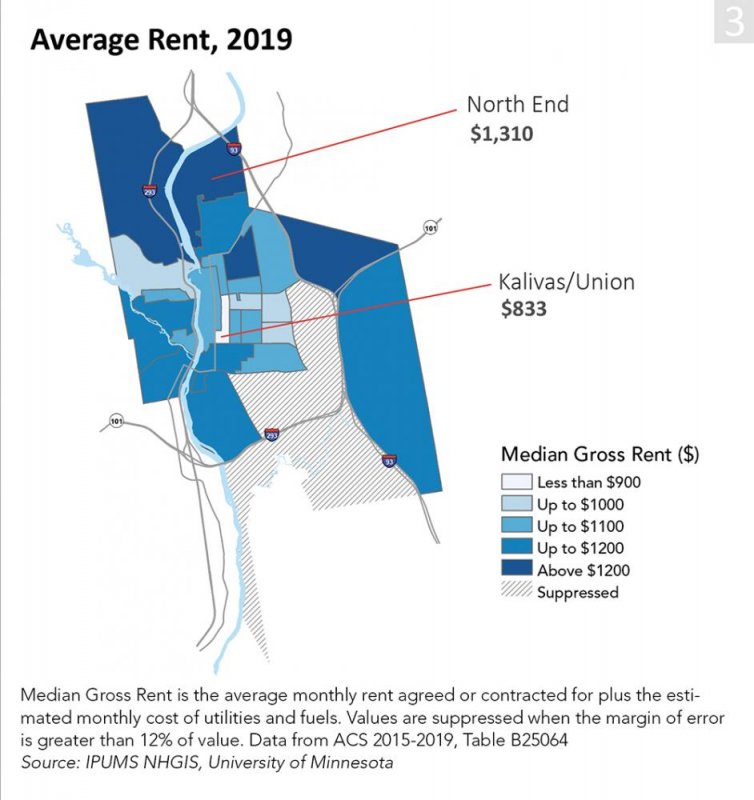

Zoning didn’t create the concentrations of poverty we see in the city today, but it has maintained them, keeping the city’s poor in a handful of center city neighborhoods by slowing the construction of multifamily housing elsewhere. This has kept housing and rental prices higher the farther away from City Hall you go, creating a series of invisible walls that have kept many of the city’s most disadvantaged residents from leaving the urban core.

The Manchester City Government is now seeking public comments to help it rewrite its zoning laws, which will be updated at the end of the year. A better understanding of Manchester’s housing history may help planners address some of the city’s thorniest housing problems and may help planners design more equitable solutions for the future.

Pockets of Poverty and Wealth

“The high rental costs have limited the housing options available to people at nearly every income level in the city,” observed an April 2021 report by Mayor Joyce Craig’s Affordable Housing Taskforce. The high housing prices have hurt not just low-income residents, the report said, but also young professionals, senior citizens, families, and middle-class residents — and it has only been exacerbated by the pandemic.

The statistics paint a gloomy picture for any aspiring homeowner or renter. In the decade up to 2020, median sale prices for all homes in Manchester increased by 42%, up from $190,000 to $271,000, according to online data from the NH Housing Finance Authority (NH Housing). In the decade up to 2021, the median rent (including utilities) for a two-bedroom apartment in Manchester increased by 58%, up from $976 to $1,546 per month, according to a July 2021 report by NH Housing.

The same report estimated that for the median apartment to be affordable, meaning that rent and utilities cost less than 30% of the occupants’ combined monthly income, the renters would need to earn nearly $62,000 per year. This is roughly $12,000 more than the typical household of renters earns in Hillsborough County, as estimated by the NH Housing report.

Stories like Harris’s highlight one aspect of the housing crisis that was not discussed in the Taskforce’s report—even though it was mentioned in other City reports published in 2004, 2013, and 2014—that would-be renters in some neighborhoods are facing even wider earnings gaps.

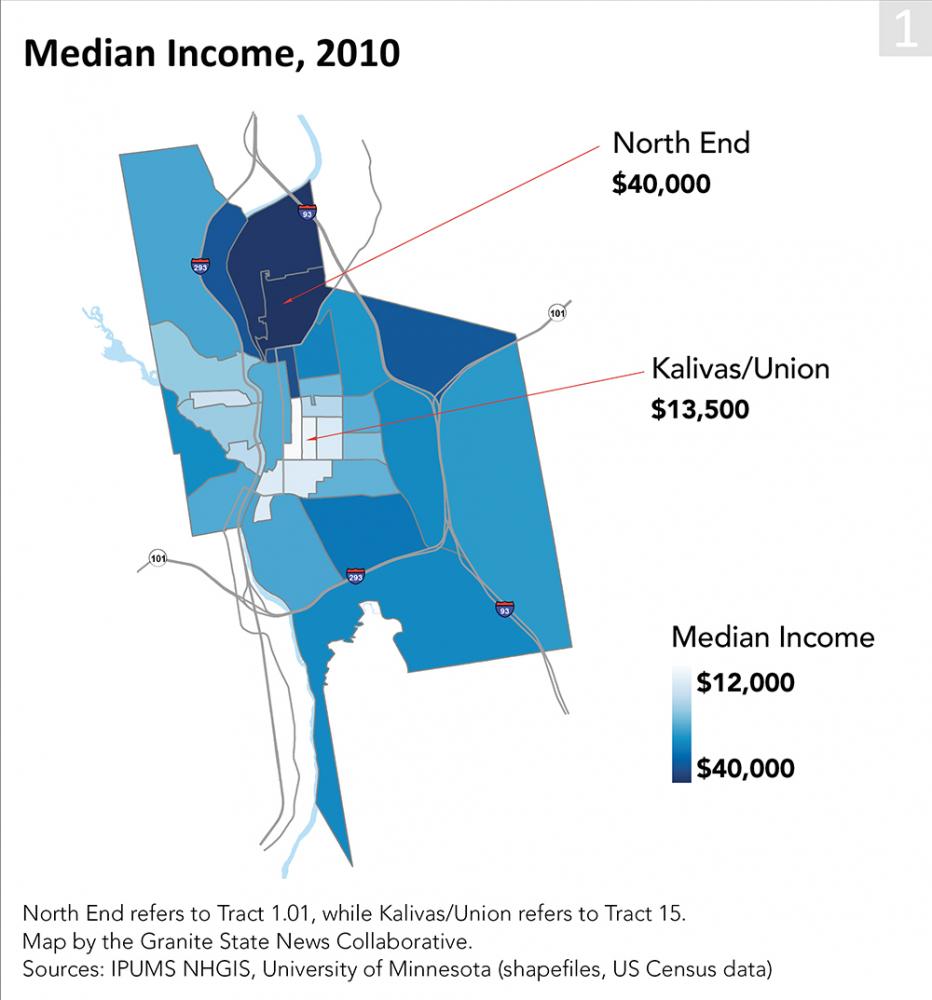

According to 2018 U.S. Census Bureau estimates, the typical household living a few blocks east of Harris (in census tract 13) earned just $46,000, roughly $16,000 short of the income necessary for the typical two-bedroom apartment to be affordable. A few blocks south, the numbers are even more grim. The typical resident living in tract 15 made just $33,000.

In the neighborhood extending south from Harris’s apartment, which includes tract 14, residents earn $23,000. Tract 14 is home to the city’s lowest households incomes and lowest rents, on average.

But the issues in these neighborhoods go far beyond the rental market. According to a NH Department of Health and Human Services analysis of census data, the residents of tract 14 were the most vulnerable in the state, meaning that they were the most likely of any community to need extra help in case of a public health disaster.

“Overdose deaths, lifetime poverty risk and communicable disease rates are also concentrated in Manchester’s most impoverished neighborhoods,” notes a 2019 City Health Department report assessing the health needs of greater Manchester.

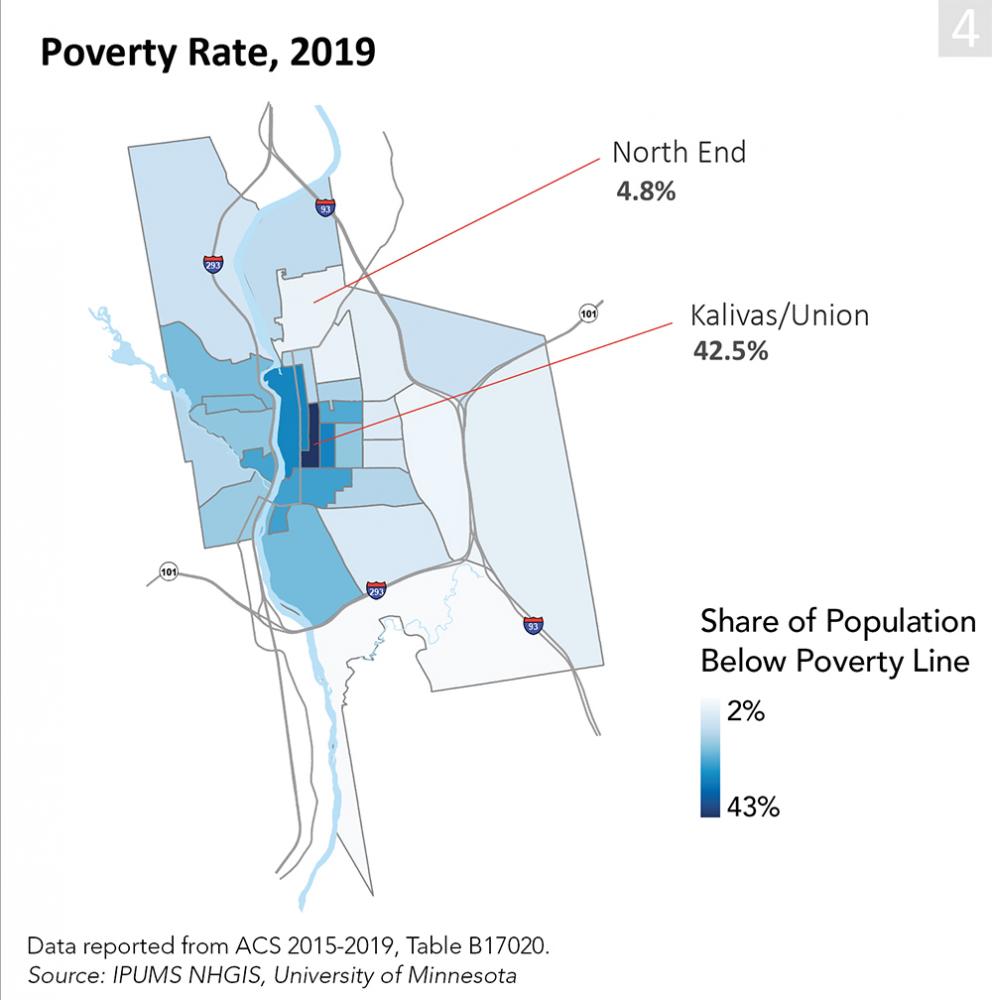

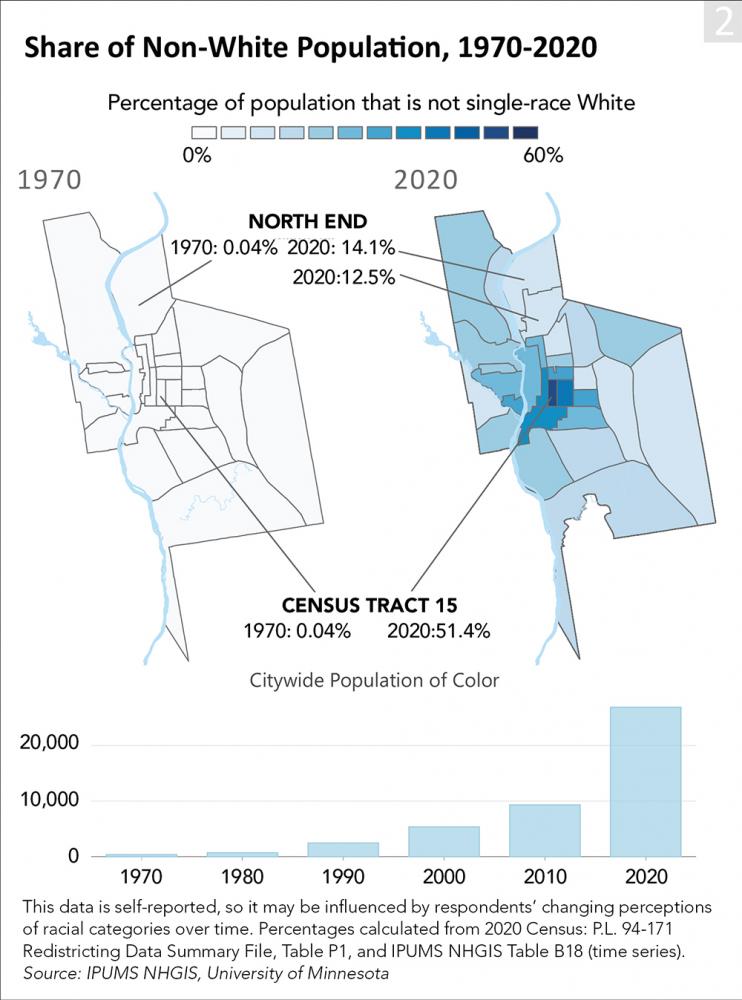

In the last thirty years, these inequalities have also taken on distinctive racial overtones. Tract 14, for example, is nearly 40% non-white, according to the 2020 census. Right next door, tract 15 was the only majority non-white census tract in the city or state.

By contrast, the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods are expensive to live in and overwhelmingly white. In one part of the North End, an elite enclave since the late 1800s, the poverty rate is eight times lower than in tract 15, median incomes are three times higher, rents are 50% higher and the population is 87% white.

Why did these two parts of the city develop so differently? There are no easy answers to this question, nor are there easy solutions. “I think city planning, especially for people who want diverse cities, is extraordinarily challenging,” says Elliott Berry, co-director of the Housing Justice Project at NH Legal Assistance (NHLA). “Unfortunately, sincere efforts to create diverse spaces [have] sometimes spurred wealthier residents to flee to suburbia.”

He adds, “It’s not easy for planners to find the sweet spot.”

Historians and housing experts suggest that the causes of center city’s challenges, while multi-faceted, can be reduced to two issues: the inequalities created by the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company’s discriminatory housing policies in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and the barriers to undoing those inequalities that have been erected by local land use zoning laws since the 1920s.

Created by Amoskeag

“What’s a ‘company town’?” asks America’s Library, an educational program from the Library of Congress. “In case you’re not sure, the story of the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company in Manchester, New Hampshire, is a good example.”

Company town, planned city, manufacturing utopia—these are some of the buzzwords that come up when reading about Manchester under the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company, the mammoth textile producer that reigned over Manchester until the company’s collapse in 1935. That lofty language reflects the company founders’ sky-high aspirations—driven, as one historian has written, by a desire to improve upon “the grimy industrial cities of Europe, where a permanent underclass toiled in the mills”—and hints at the reach of the company’s power.

So why didn’t things turn out as perfectly as planned? When Robert B. Perreault, a local writer and historian, is asked to speculate as to why the city’s inequalities developed in the way they did, he begins his story in the late 1840s, when Manchester was freshly incorporated, but already tightly controlled by Amoskeag. “Since Amoskeag owned much of the land on both banks of the Merrimack River,” Perreault says, “the company could indeed dictate how the land would be used, for example, where the downtown business district would be, and even what kind of building and business blocks would go where.”

The company’s holdings were vast. By 1838, Amoskeag already owned most of the still-unincorporated city, totaling some 26,000 acres of land—more than all of Manchester today—including 15,000 acres on the east side alone.

Amoskeag’s leadership wanted to use that monopoly power to design the city from the ground up, as had been done in other industrial cities like Lowell, Mass-achusetts. This included laying down a street grid and constructing worker housing, most of which was built between Elm, Canal, Hollis and Pleasant streets.

According to Aurore Eaton, a local historian, the company houses offered comfortable living. “Those who lived there had a sense of security and a certain ease of living,” she wrote in her 2015 history, The Amoskeag Manufacturing Company. For employees lucky enough to get an apartment, “the workplace was a short walk away, and there was quick access to many of the necessities of life,” including entertainment in the downtown and the railroad station just down the street.

Amoskeag Manufacturing Company worker housing in 1895. Courtesy of the Manchester Historic Association.

The kicker was that not all employees were allowed to live there. “The company rented flats to its overseers, second hands and skilled workers,” Perreault says, many of whom were American, though the invitation was extended to any skilled workers that the company hired, regardless of their nationality. (Amoskeag recruited heavily from Scotland and England, as well as Germany and Sweden.)

Meanwhile, Perreault says, “unskilled immigrants weren’t even included on the waiting lists.... That is how various ethnic neighborhoods came about, as these unskilled immigrants sought housing elsewhere.” Like their more privileged coworkers, the unskilled immigrants looked for housing that was within walking distance of both the mills and the train station. The natural barrier of the river, which closed off much of the west side, left them with only a few neighborhoods from which to choose.

And so, “when the first very large ethnic group of unskilled workers to arrive in Manchester, the Irish, got off the train,” Perreault says, “the closest residential neighborhood with a lot of multifamily affordable housing was census tract 15.”

Thus began the pattern of poverty in center city. “When the French Canadians began arriving in greater numbers after the Civil War,” Perreault continues, “they, too, got off the train and headed for the same neighborhood.”

But with each generation of new arrivals, as the Amoskeag Company scoured North America and Europe for cheaper labor, the previous generation of workers needed a place to go. According to historians Scott and Stephanie Roper, who wrote a book about Manchester’s labor movement in the early 1900s, the company dealt with this issue by drawing on its immense land holdings. When workers needed a place to go, the company would open up a new part of the city and would encourage the immigrant community to move together, maintaining the informal ethnic enclaves and clearing the way for new arrivals.

After the west side opened for development in the early 1880s, for example, French Canadians began to move there en masse. “Amoskeag had a policy of selling plots of land in this new neighborhood to loyal, longtime mill workers whereby they could become homeowners via an affordable plan set up by the company itself,” Perreault says. “Much of the Franco-American West Side neighborhood was developed this way.”

Child laborers from the Amoskeag Mills in 1909. One child, far left, lived in worker housing, while the rest, all with French names, lived on the west side of the river. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Perreault says that versions of this story repeated itself for each new group of arrivals, including from Poland, Greece, Russia and elsewhere in eastern Europe. Each ethnic group found affordable housing in center city, then quickly swelled in numbers in just a few years. Once the ethnic community had grown wealthier, they moved to a new neighborhood, and the cycle began anew.

But the company’s strategy of keeping the ethnic groups intact and separated from one another also reveals a strikingly utilitarian aspect of Amoskeag’s community.

According to the Ropers, the company’s housing policy was motivated by strong opposition to workers’ rights. By keeping the poorest workers divided, then providing extravagantly for the better-off workers as needed, the company kept many workers in their thrall, thereby slowing the development of the local labor movement.

From the company’s perspective, this strategy worked. Unions couldn’t get a foothold in Manchester until 1918, and there wasn’t a single major strike at the Manchester mills until 1922.

But the policy of ethnic segregation had some nasty side effects even at the time. The workers were so divided that they sometimes came to blows, especially in public spaces like the city parks. In 1854, native-born Americans clashed with the first wave of immigrants, the Irish, earning Manchester a mention in the New York Times for a riot that ended with the destruction of tenements on Elm Street and an attack on a Catholic Church, all occurring in “the Irish portion” of the city.

Tenement housing in Manchester in 1936. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Fifty years later, the now-settled Irish clashed with the newly-arrived Greeks after a wayward hit from an Irish baseball game struck a Greek man in the face, breaking his tooth and triggering a 2,000-person riot.

These divisive policies also appear to have done a number on public health in the ethnic neighborhoods. One 1917 U.S. Department of Labor study of infant mortality rates in Manchester found that the poverty and sub-standard housing were strongly correlated with higher death rates. Mothers renting in the city’s most affordable housing developments had the highest infant mortality rates overall, at 211.4 deaths out of every 1,000 live births – far above the city average (165.0) and even double the rate in New York, the author noted with alarm.

Given the severity of the problem, the author warned that even though these issues were at that time confined to only a handful of areas, they threatened to spread across the city “unless controlled by adequate restriction”—an explicit call for the barriers between the poor and wealthy communities to be further strengthened.

By the time the Amoskeag company was on its way out in the 1920s, under pressure from new competition in the textile market from the American South, the city’s neighborhoods were sharply delineated by ethnicity and economic class, but the corporate hand that had built those walls was rapidly weakening.

The Amoskeag Company’s dissolution in 1935 could have been an opportunity for these walls to come down and the city to integrate. But the last 90 years of local zoning policy has helped prevent that from happening.

Preserved by Zoning

“Zoning is an expression of what the citizens want their community to look like,” the planning team from Manchester’s Planning and Community Development Department states in emailed comments to the Collaborative.

Does the community want to be one of stately houses on sprawling lots? Does it want to have a bustling downtown, full of small businesses and apartments?

“As the citizens’ desires change over time, so should zoning ordinances,” the planners write, which is why a city’s zoning “will always be a product of its time.”

Manchester’s zoning laws have mostly maintained the status quo established by the Amoskeag Company, continuing the pattern of center city poverty and North End wealth that has existed since the late 1800s. “Zoning is a reinforcing phenomenon,” says Berry from NHLA.

As the city prepares to update its zoning laws, following the adoption last August of the new Master Plan, a better understanding of the city’s zoning history may help residents and planners design a more equitable city for future generations.

One key to the success of this project is a clear-eyed understanding of the politics behind the zoning debates.

According to the work of William Fischel, a retired Dartmouth economist and national expert on zoning, one of the major causes of zoning drama can be understood as simple economics.

“The dominance of homeowners and their touchiness about their main asset explain why nearly every suburban zoning ordinance puts the single-family, owner-occupied home at the pinnacle of uses to be protected,” Fischel wrote in a 2004 history of American zoning.

“For most of them, home is by far their largest financial asset and, unlike owners of corporate stock, homeowners cannot diversify their holdings among several communities,” he explained.

“Fear of a capital loss to their major asset and desire to increase its value motivate owners of homes to become ‘home-voters,’” he wrote, advancing their own interests each time they participate in local elections and public hearings.

According to Fischel, the fear- and finance-driven behaviors of this powerful group, catalyzed by a series of perceived threats to home values over the last century, help explain why zoning laws have gradually tilted to protect the investments of existing homeowners over the last century. Zoning laws do this by reducing the number of homes that can be built in a given area, typically through the use of single-family zoning. Doing so increases competition for existing homes and apartments, which in turn increases prices, making the path to owning or renting harder for any newcomers.

The additional observation that white Americans own homes at significantly higher rates than Black Americans, on average, has given the current debate around zoning an especially volatile political charge.

In 1916, the first comprehensive zoning law in America was established in New York City. And so began what Fischel called “the land-use revolution.”

Over the next few years, community-wide zoning laws spread around the country, expanding and formalizing the systems of private deed restrictions or limited-area zoning laws that communities had experimented with in the preceding decades.

Zoning’s adoption was lightning fast. Between 1916 and 1936, Fischel wrote, the number of cities with comprehensive zoning laws increased from eight to more than 1,300. The City of Manchester entered the fray in 1927 after the Manchester Planning Board successfully lobbied the legislature in 1925 to allow towns around the state to write their own zoning laws.

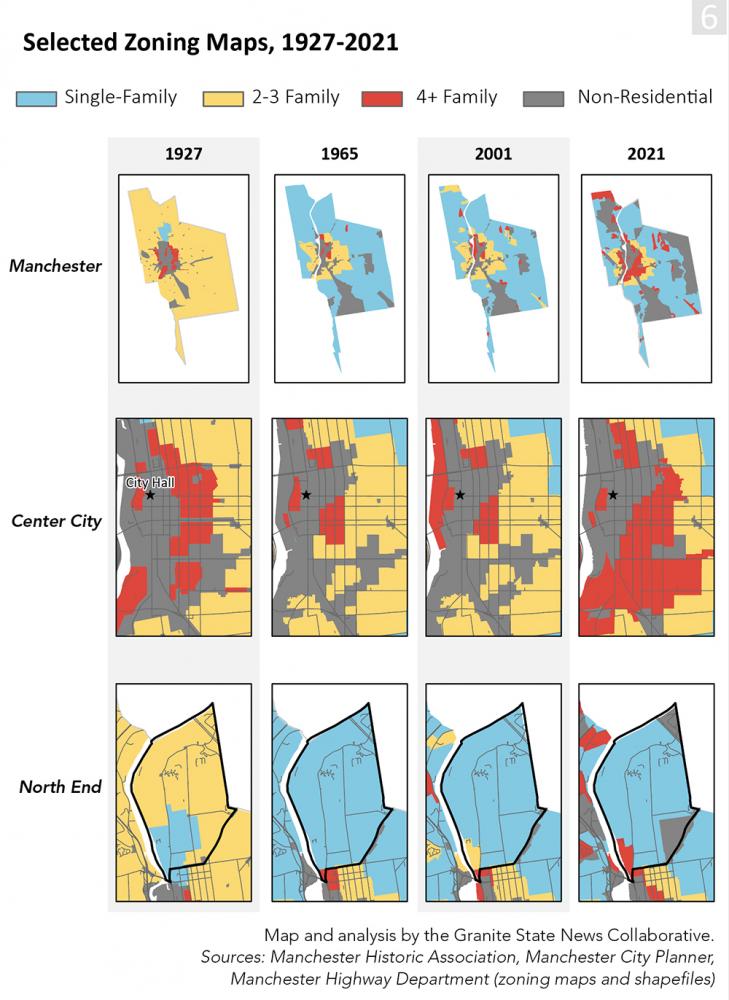

When the new ordinance was passed, Manchester’s residents were presented with a three-tiered vision for their city’s future. At the top of the pyramid was the roughly 2% of the city that was restricted for single-family residences—the most expensive type of housing. All of the land reserved for single-family was in the North End.

In the second tier was the more than 80% of the city that also allowed two-family homes, covering most of the area outside the urban core. Two-family homes were a staple of the immigrant community in mill towns across the Northeast.

Finally, there was the 2% of the city that also allowed multifamily, almost all of which was located near the mills on either side of the river. In contrast to the Amoskeag policy, which had erected one wall by preventing unskilled immigrants from living too close to the mills, the new zoning law restricted the movement of this demographic group on two sides by preventing its spread into the suburbs as well.

With the establishment of this new law, zoning helped ensure that the poverty concentrated in center city would not spread outward, while the North End would continue as a enclave of the city’s economic elite. In Manchester, as was true around the country, the full effects of zoning would take some time to play out. By the early 1960s, all over the country, the arrival of the interstate system meant that newly-accessible suburbs offered exciting possibilities for center city residents. More jobs became accessible, as did affordable housing far from the urban core.

But these opportunities also threatened to upend the status quo in cities, Fischel wrote, and those who worried about a mass exodus of residents to the suburbs. This triggered a new wave of revisions to many cities’ zoning laws.

In NH, this trend appeared in the form of growth management zoning. Under this framework, NH towns used zoning to help address rapid population growth between 1960 and 1990. The towns feared that residential development would increase school enrollments, requiring expenditures far in excess of the property tax revenue generated by the additional housing.

To prevent that development, many towns introduced zoning policies that were designed to slow or stall population growth by making it difficult for new units to be built at all – often through the widespread use of single-family zoning with minimum lot sizes.

Between 1927 and 1965, single-family zoning’s coverage expanded from two to 70% of the city, making it by far the dominant form of housing within city limits. This meant that without permission from the zoning board, it would be impossible to build more of the two-family structures that had been so popular at the beginning of the century. Meanwhile, the amount of land reserved for two- and three-family homes plummeted, dropping from 80% to 10%. Multifamily housing was left with the smallest amount of land of all, at just 1% – nearly all of it in center city.

Since 1965, the story of Manchester’s zoning has been one of gradually opening up more parts of the city for multifamily development – though the trend of high-density housing in center city and low-density housing elsewhere has largely endured.

This has become especially noticeable in recent years as the racial makeup of center city neighborhoods has dramatically transformed.

Between 1965 and 2000, relatively little on the zoning maps changed. According to one map from late 2000, the zoning law’s focus on single-family had lessened slightly since 1965, dropping from 70 to 67% of the city’s area. Medium-density housing, including two- and three-family homes, increased slightly from 10% to 13%. Meanwhile, multifamily accounted for only 3%, increasing just two points over four decades.

Changes in the last twenty years have been much easier to see. According to an updated zoning map provided by the City Planner’s office in late 2021, the area reserved for single-family zone had fallen from 67% to 54%. Medium-density dropped from 13% to roughly 7%. Meanwhile, multifamily grew from from 3% to nearly 10% – the greatest share of land allocated to multifamily in the city’s zoning history – and spread to several new neighborhoods outside of center city.

These changes echo the clear but limited progress that many communities in the state have made toward providing more affordable housing in the last thirty years, spurred into action by a NH Supreme Court opinion in the early 1990s and a follow-on piece of legislation approved in the late 2000s.

In 1991, the NH Supreme Court ruled in the case of Britton v. Chester that all towns that handle their own zoning must allow “realistic opportunities” for the development of housing that is affordable to low- and moderate-income families. They must, the court said, because it is their responsibility to share the burden of population growth, rather than putting up obstacles to keep outsiders from coming in.

“The zoning ordinance evolved as an innovative means to counter the problems of uncontrolled growth,” the court wrote. “It was never conceived to be a device to facilitate the use of governmental power to prevent access to a municipality by outsiders of any disadvantaged social or economic group.”

The court likened these actions to the construction of physical barriers, like the walls of a medieval fortress, warning that towns “may not refuse to confront the future by building a moat around themselves and pulling up the drawbridge.”

Housing advocates hoped that the Britton decision would lead to rapid improvements in New Hampshire’s housing market, very little changed over the next decade and a half. Towns continued to embrace ordinances that made it difficult, if not impossible, to build multifamily housing.

In 2008, after years of debate, the NH Legislature passed the Workforce Housing Law (RSA 674:58-61), which required municipalities to comply with the Britton decision by providing “reasonable and realistic opportunities for the development of workforce housing, including rental multifamily housing.”

Unfortunately for some of the New Hampshire’s newest residents, those changes have come rather slowly, according to a 10-year retrospective on the Workforce Housing Law by NH Housing.

Especially in light of the housing crisis, the authors wrote, “it is surprising to discover how little progress has been made by some municipalities to address the requirements of the workforce housing law since the legislation was enacted over 10 years ago.”

This has become especially noticeable in the last 30 years, as Manchester’s center city has become increasingly poor and non-white, leading to the situation we see today.

“This map of 100 years of zoning boundaries in Manchester shows that there has been a consistent policy of keeping multifamily contained,” says Elliott Berry from the NHLA. “For a multiplicity of reasons, including neighborhood resistance to change, expanding opportunities for lower wage workers and other low income people to live in more desirable environments has proven to be very difficult.”

City government, he says, can continue to help change this situation for the better.

“Zoning isn’t the full answer,” he adds, “but without changes to zoning, it’s impossible to make headway with any of the other issues.”

The City is in the process of drafting the new zoning code, and the planning team wants citizens to get involved. According to the City’s planning team, residents can learn more and provide comments at www.manchesternh.gov/landusecode, and they can participate in person at a two-day public outreach event, titled Code-A-Palooza, which will be taking place this upcoming March.

“We encourage any members of the public interested in learning more about the City’s zoning to attend this event and help us work towards a new host of regulations that work better for everyone!” the planning team said.

For would-be renters like Harris and Allen, changes to the zoning regulations couldn’t come soon enough. Last July, the couple was sitting at home watching a movie when someone fired a shotgun right in front of their apartment.

“It made my Queen jump out of bed,” Harris says, referring to his girlfriend. “For a second, she was scared,” fearing that stray rounds might come into the house. Harris initially didn’t think the shooting was worth worrying about. “Ah, it’s Fourth of July, they’re just playing,” he thought. “But then we find out. Nah, it was actually shooting at somebody.”

That was all he needed to know. “And I was, ‘Oh, we got to go.’”

He and Allen are currently saving up to find an apartment in another part of the city.

With rents still sky high, however, leaving center city remains out of reach.

Bill Wilkinson contributed research to this report.