Hate crimes are on the rise, critical race theory has become a culture war touchstone and NH’s lack of diversity may cost the state its first-in-the nation primary status. All of it underscores not only the need for, and the challenges facing, diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) training, but the importance of understanding what effective DEI training is about.

One thing is clear, though. More companies and institutions are recognizing the importance of having diverse and equitable workplaces and that they may not have the expertise to effectively address such complicated and fraught issues in-house. Increasingly, diversity officers are joining leadership teams at major corporations, colleges and universities, and many businesses and organizations are hiring DEI experts to help them take a hard look at their own cultures. The global diversity and inclusion market reached $7.5 billion in 2020 and is expected to reach $17.2 billion by 2027, according to a 2022 report by Research and Markets.

And as times have changed, so are people’s understanding of diversity, equity and inclusion. Rebecca Sanborn, whose firm, Sanborn Diversity Training Solutions in Derry, focuses on DEI training and support, points to the cultural awareness that shifted since the murder of George Floyd and the MeToo movement. “Things have happened that have made people sit up and say there are things in society that people need to deal with,” she says. And the economic component to DEI should not be overlooked. “Diverse companies are more financially successful and more dynamic when they allow all voices to be heard. We need to listen to other voices,” Sanborn says.

While NH is one of the least racially diverse states in the country, with 92.8% of people identifying as white, according to 2022 U.S. Census Bureau statistics, in places like Hillsborough County’s census tract 15, the center of Manchester, the white population is 37%.

James McKim, president of the Manchester NAACP and managing partner of Organizational Ignition, says making global statements that NH is a “white state” ignores “hyper local realities” and he emphasizes that diversity is a broad concept. “We’re talking about race and gender, age, ability, a whole host of personality characteristics that make up this concept of diversity,” he says. “We have tons of diversity in that sense across the state.”

Manchester NAACP president and Organizational Ignition Managing Partner James McKim conducts a DEI training seminar. (Coutesy of James McKim)

Manchester NAACP president and Organizational Ignition Managing Partner James McKim conducts a DEI training seminar. (Coutesy of James McKim)

The benefit to DEI training, McKim says, is it engages people in understanding diversity in all its forms and helps to create workplaces and communities that draw people in. “It’s not about just trying to get Black people in the state. When we have organizations and societies that value an individual for what they bring, that’s what is attractive to people,” he says.

And it’s a balancing act, he says. “We all exhibit the paradox of diversity. We all think we’re different, and on the other hand, we believe we’re just like everybody else. Our organizations and leaders need to understand this paradox and walk that fine line,” McKim says.

More Than the Bottom Line

McKim has been working for more than 30 years to help small and large organizations be more efficient. His experience, which includes serving as chief of staff of the global technical training division for Hewlett Packard Enterprise, which he left in late 2018 to do strategic consultancy work, is being applied today in the DEI training and support he provides for organizations, including the NH Judicial Branch.

McKim, who took office as NAACP president in February 2020, says when he started his consulting practice, he planned to write a book about the benefits of diversity for individuals. But then, he says, the “terrible summer of 2020 happened,” and his intentions shifted. Many of these types of books at the time, he explains, were being written from a social justice perspective but not about diversity from an organizational performance perspective. “And this is what gave me the idea to write a book and start working

with organizations.”

McKim’s book, “The Diversity Factor: Igniting Superior Organizational Performance,” was published in 2022. It defines various terms such as diversity, equity, inclusion, implicit bias, neurodiversity and gender, and explores the ways in which DEI affects systems within a workplace.

DEI training and support for companies and organizations, McKim says, is about more than simply checking a box, and when it comes to achieving an organization’s mission, having a diverse, equitable and inclusive workplace is about more than just financial viability. While this is something many nonprofits already realize, he says, “for-profit companies should also be aware that a long-term commitment to DEI is crucial for organizational growth.”

McKim cites an organizational assessment model created by management consultants Universalia that views corporate performance as the balance between efficiency, effectiveness, relevance and financial viability. McKim works with organizations to focus on these perspectives. “If you think about organizational performance from those four perspectives, you have a more wholistic view of the performance of an organization than just the bottom line,” he says, citing research from various management consultancy firms such as McKinsey. “Organizations that embrace DEI are 27% better at value creation than their peers. In terms of efficiency, organizations embracing DEI are 87% better at making decisions, 70% more likely to get into different markets and do well, and 35% more likely to outpace their peers in earnings before interest and taxes.”

A Strategic DEI Plan for NH Courts

One of the organizations that McKim is assisting in this way is the NH Judicial Branch. The branch’s plan to address diversity and inclusion issues started when Chief Justice Gordon MacDonald decided the courts needed to look closely at the issue, says NH Superior Court Judge David Ruoff. “Other states had been looking at how the court system is dealing with issues like this, and we had nothing,” Ruoff says, adding that then-newly appointed Chief Justice MacDonald asked him and retired Judge Susan Carbon in 2021 to set up a steering committee with a plan the Supreme Court could implement.

One of first things Ruoff says the committee looked at was the lack of data for measuring diversity and inclusion. “The court system was not set up to do self-reflection like this, to look at how different results might be compared across different demographic groups.”

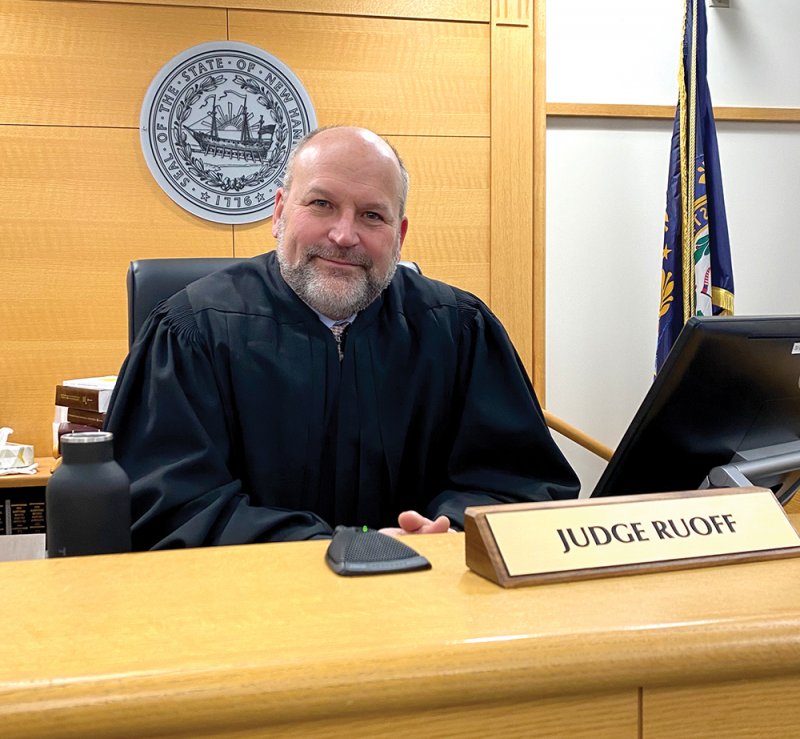

NH Superior Court Judge David Ruoff. (Courtesy of the NH Judicial Branch)

NH Superior Court Judge David Ruoff. (Courtesy of the NH Judicial Branch)

Ruoff says the goal of the Diversity and Inclusion Initiative is not to create more diversity within the judiciary itself because NH judges are appointed by the governor and are typically chosen from the NH Bar. To date, NH has had only one Black judge, Judge Ivorey Cobb (pictured), who was appointed in 1964. “In order for the judiciary itself to get more diverse, we need the bar to become more diverse. That’s the feeder program,” he says.

The strategic plan, which was revised and adopted by the state Supreme Court in July 2022, addresses staff trainings, self-evaluations, increasing diversity, addressing institutional racism and cultural bias, engaging in public outreach, and engaging in internal and external communications. Ruoff says the plan also includes a group in charge of data collection both internally and externally, as well as a training and retention group.

“We have a hard time retaining our people for a number of reasons, and diversity and inclusion training is a small part of fixing this. We’re trying to make sure our system runs fairly and that it treats all people fairly, no matter where they come from or what color their skin is. That’s our constitutional obligation. And we need to start measuring that.”

Ruoff says diversity and inclusion training has been an “education in itself” in terms of looking at what kind of training works. As a drug-court judge, he says he is a big supporter of evidence-based training methods and that this approach is one of the criteria used to vet those who provide trainings for the courts.

“We need to know that the training isn’t going to tell them they’ve been wrong or bad,” he says. “There are not a lot of minorities that work in the court system; most of the people that are minorities are defendants in criminal cases. We employ many people that might be alienated by the wrong way of going about this.”

While working with Gov. Chris Sununu’s Commission on Law Enforcement Accountability, Community and Transparency (LEACT), McKim says he dealt with reports of discrimination “all the time.” Working on the Court’s DEI initiative, he has been able to offer advice.

“We don’t capture enough data about the demographics for people who go through the court system,” he says. “Judge Ruoff pointed out that people inside the court system don’t truly understand the biases they hold and how that impacts the services they provide.”

McKim says the judicial branch needs to know what people’s interactions are like when they deal with the court. “Any organization should examine how it interacts with its customers. Is it being equitable, is it being inclusive, is it being standoffish? Is it being rude?”

And trainings are only part of solution, McKim says. “The whole culture needs to be set up. It’s about change.” Organizations, he says, whether the court system or a large company, should have strategic goals and objectives and must ask themselves if management is ready to lead this change. “No training works unless you have the environment for that training to be successful and utilized.”

Ruoff says the judicial branch is practicing a “train the trainers” approach, working with experts from the National Center for State Courts, so that leaders can learn how to speak to people without alienating them. “They have specialists in evidence-based data collection and have been very, very helpful,” he says.

A Commitment to Changing Behavior

NFI North, an accredited multi-service nonprofit that employs over 400 people across NH and Maine, is another NH organization dedicated to making systemic changes in the area of DEI, McKim says. The agency, which provides a range of supports to clients, including specialized education, counseling, supported employment, care management, foster care and more, initially hired McKim to provide an assessment for their organization, says Paul Dann, NFI North’s executive director.

NFI North employees attending virtual DEI training. (Courtesy photo)

NFI North employees attending virtual DEI training. (Courtesy photo)

Since then, NFI has added a “B” for Belonging to its definition of DEI. “We want to be the best organization for employees and the people we serve, so we asked [McKim] to come help us take a look to see where we are,” says Dann. “As part of our core curriculum, we’ve always had a full day of training in cultural foundations and strategies to be accepting and inclusive but always want to do more.”

McKim did a brief training and helped NFI North “begin to think about how to be more inclusive, to create more equity and belonging,” Dann says, adding that following McKim’s work, NFI North is moving ahead with a DEI and Belonging committee that represents a cross section of the people it serves as well as management and non-management staff leadership trainings. “One thing we realized is that the more we’re able to be welcoming of all people, the better we are organizationally,” Dann says.

Dann says bringing in as many people as possible is crucial and that DEIB is one of the foundational pieces to NFI North’s strategic plan. “I think you’d find we’re living and breathing DEIB as a philosophic approach. It’s a normative community approach. We believe people are social, and everyone wants to belong in a positive environment that’s meaningful,” he says.

McKim says that in the learning and development world, there are different evaluation levels regarding the effectiveness of DEI training and that NFI North scores high. Level 1 asks: “did the person taking training learn something? Did they pass the test? Did they learn what trainers wanted them to learn?” A higher level of evaluation, he says, is about behavioral change.

“We’re doing this work to change behavior,” McKim says. “We need to evaluate whether the individual changed behavior in doing their work.”

And measuring success when it comes to DEI trainings depends on how success is being defined, McKim says. “We know that 80% is going to be forgotten in two weeks if the work isn’t continued. If people expect training to be the answer, it’s not. It’s only part of the solution.”

And as Judge Ruoff points out in his work on the committee, McKim says, “shame and blame” does not work. “An effective training draws people in rather than calling them out. It creates allies. It’s important to build empathy.”

Attorney Terri Pastori of Pastori/Krans cited practical reasons for employers to provide DEI training. Claims of discrimination in the workplace can be avoided with proper training and support for employees and managers, she says, adding that unconscious bias and microaggressions could create legal responsibility for employers. An unconscious bias situation where women or people of color aren’t getting certain positions, she explains, increases the chances of a claim that they were subjected to discrimination or harassment.

“When behavior is allowed to occur or fester, that can increase exposure for an employer,” Pastori says. “In that regard, I’m a big believer in DEI training so they can spot issues.”

This begins by identifying behavior that isn’t consistent with company culture or the law. “Cultural expectations can go above and beyond legal expectations. There’s a business case to be made for having people from all backgrounds in a diverse workplace. You build a better company that way.”

When cases do arise, one problem in NH, Pastori says, is that the state doesn’t adequately fund the Human Rights Commission. “The idea is to have a less formal agency than the court system for employees to file pro se and raise complaints—to have an investigation conducted in a reasonably prompt manner. If we don’t fund the commission, we’re not going to have enough investigators to investigate charges and have them resolved informally.”

A Focus on LGBTQ Issues

Empathy is something Sanborn, a former lawyer, of Sanborn Diversity Training Solutions, focuses on in the DEI training and support she provides. While practicing law, Sanborn focused on family law, estate planning and business law. What she enjoyed the most, she says, was helping people and “putting something positive into the world.”

Sanborn (pictured) does this today by offering DEI training for businesses and nonprofits around LGBTQ matters. “I provide what I like to call LGBTQ cultural competency training. Things like ‘what does it mean to be transgender, non-binary, queer?’”

Sanborn (pictured) does this today by offering DEI training for businesses and nonprofits around LGBTQ matters. “I provide what I like to call LGBTQ cultural competency training. Things like ‘what does it mean to be transgender, non-binary, queer?’”

Getting at the meaning of these terms, Sanborn says, is largely about empathy building. “We talk about best practices for interacting with the LGBTQ community from the point of view of employees and coworkers and the public-facing side interacting with customers.”

Sanborn, who refers to herself as a proud bisexual woman, started her business about two years ago and says that while practicing law, there came a point where she realized it was time for a career change. “I’ve always been drawn to teaching. Even as an attorney I felt like I was educating my clients,” she says. “As a kid I was fascinated by the civil rights movement. These things fed my soul. So, I settled on becoming a DEI professional and decided I wanted to do the training. Then I narrowed it down further to the LGBTQ community.”

Sanborn has both a Diversity and Inclusion certificate from Cornell University and is also certified in advanced employee relations. Her curriculum, which has evolved, she says, is tailored to various organizations such as nonprofits and health care organizations. She recently formed a partnership with Franklin Pierce University with the hopes of training faculty and possibly students.

“LGBTQ students face a lot of barriers,” Sanborn says, explaining that college-age students are often dealing with acclimating to the college environment and figuring out their identity. “They’re trying to figure out whether it’s safe to come out, and there are more instances of anxiety and depression.”

This anxiety and depression, she says, is related to minority stress, which she describes as the stress that goes over and above daily stress everyone deals with.

“[Minority stress] affects historically marginalized groups,”she says, “and it’s the result of prejudice and discrimination in society particularly due to microaggressions. Being in a constant state of stress can lead to health problems such as high blood pressure as well as mental health issues like anxiety and depression.”

Training Students for a Diverse World

Dr. Nadine Petty, chief diversity officer and associate vice president for the Division of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at the University of NH, has worked in education for 22 years—16 in a higher education setting. Having spent her formative years in Jamaica, Petty brings an international lens to her work.

UNH’s mission, Petty (pictured) says, is to prepare students for an increasingly global society. “Many of our students, particularly if they choose to leave New Hampshire and go to places that are more diverse, are going to have to work with people who are not like them, who don’t have the same backgrounds,” she says. “If they’re ill prepared for that, we’re not setting them up for success. We have to, as humans, be able to work with people who have different opinions from us and to do so in productive ways.”

UNH’s mission, Petty (pictured) says, is to prepare students for an increasingly global society. “Many of our students, particularly if they choose to leave New Hampshire and go to places that are more diverse, are going to have to work with people who are not like them, who don’t have the same backgrounds,” she says. “If they’re ill prepared for that, we’re not setting them up for success. We have to, as humans, be able to work with people who have different opinions from us and to do so in productive ways.”

Petty, like many other professionals today, says she fell into DEI through the various roles she played throughout her time in education that exposed her to gaps in equity and inclusion for underrepresented people.

“I don’t think most people say I want to be a chief diversity officer when they’re asked what they want to be when they grow up,” she says, explaining that during her time with TRIO Student Support Services and various diversity centers, she developed “a keen awareness of where higher education and education needed to do better. I learned that I wanted to affect underrepresented populations. That’s why I’m here.”

Petty says higher education could do better for its neurodiverse population— students with disabilities such as ADHD, Asperger’s and autism. She recently convened a task force to provide recommendations for a center for neurodiversity at UNH that would represent neurodiverse students.

“I saw this as an opportunity for us,” Petty says, explaining there are also faculty and staff who are neurodivergent and would benefit from being represented.

Another initiative for the spring of 2024 includes a partnership between Petty’s office and the office of admissions at UNH that would create a pilot program addressing accessibility.

“Our data shows us that underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities, first generation students and our low-income students do not visit campus at the same rate as their counterparts.”

These students, she says, may be accepted to the university, but they’re not choosing to attend UNH. “Would you choose to go to a school you never visited?” she says. “We’re trying to tear down some barriers by creating opportunities for these students and their families to come to campus and to see what we have to offer before they make a decision about what school they’re going to. For students of color, it’s not easy to choose a predominantly white institution if you’re not already used to the culture of New Hampshire.”

Petty agrees with McKim that evaluations are key when measuring the effectiveness of DEI trainings. “We ask the participants at the end of trainings for feedback, and we use this to get a sense of whether something is being impactful or not,” she says, adding that climate surveys and focus groups are also used. “This type of work is not ‘one-and-done,’ it’s a constant gathering of feedback and a constant trying to figure out how do we meet the needs of our community members to make sure that everyone, and it’s everyone with a capital E, is being heard.”

This goes beyond just talking about race and ethnicity or gender, “which is where people’s minds tend to go,” she says. “And it can’t be forced.”

We Don’t Like to Change

A concept McKim uses in his DEI trainings is change management. “Change must be managed, but we don’t like to change as humans,” he says. “Now multiply that by the number of people in an organization and it becomes very difficult.”

While policies and procedures can be changed, McKim asks, “How do you make sure the behavior changes in a positive way? That’s what change management is all about.”

Change, McKim says, needs to be driven by executives and “many executives don’t know how to manage change from the inside.” To maintain an organization’s goals and objectives after a training, people need to be reminded of what has been learned, he says, or else “people will forget.”

Pastori agrees that an employer’s policies must be supported with a genuine commitment to change. “If you don’t walk the walk and talk the talk, it’s useless. It must start from the top down. Policies and opportunities for awareness need to be in place so the mission is embraced on a regular basis,” she says.