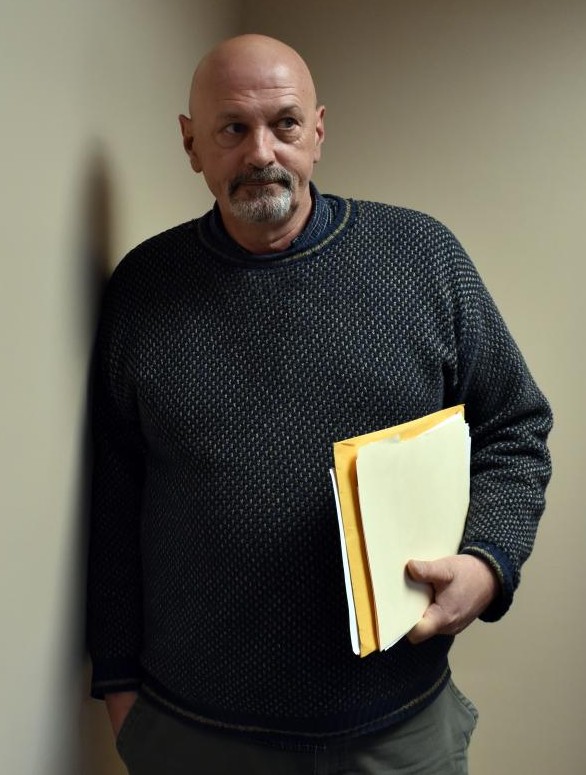

Editor's note: Laconia Daily Sun Managing Editor Roger Carroll, 59, experienced firsthand how the state's mental health system works, and doesn’t work, when he went through a personal crisis and sought help in November 2018. He wrote about his experiences in three parts in the Laconia Daily Sun to shed light on that system and help remove the stigma surrounding mental health. All three parts are presented here in one story. This story was produced by The Granite State News Collaborative as part of its Granite Solutions reporting project. For more information visit www.collaborativenh.org .

It was the week before Thanksgiving and my world had changed from that of a working journalist with the freedom to come and go as I pleased to being held in a locked psychiatric facility where staff checked on me every 15 minutes to make sure I was OK.

“Are you here voluntarily?” one of the other patients asked warily.

I was, but I wasn't free to leave.

Another patient, a young man in his 20s, seemed to assume I was there because of a drug problem.

“I don't do drugs,” I told him.

“But you realized you weren't right in the head, so you reached out for help?”

I nodded.

“Right on,” he said, extending his hand across the table in the dayroom. “Good for you.”

I shook his hand and felt a tiny bit of my humanity returning, as if I were receiving a transfusion.

We were both in blue paper hospital scrubs, the kind designed to not bear the weight of a person who might try to turn an article of clothing into a makeshift noose. Our rooms had no electrical outlets and any metal handles that might be fashioned into a cutting device had been removed. The chairs in the dayroom must've weighed 60 pounds, presenting an obstacle to anyone who might be inclined to pick them up and use them as a weapon or toss them through the windows, which appeared to be some type of reinforced glass.

I was in the Designated Receiving Facility at Franklin Regional Hospital, one of a handful of such inpatient facilities in the state where patients go to be treated for mental illness.

I was there for four full days and parts of two others.

My journey started with a regularly scheduled Tuesday visit to my therapist at Lakes Region General Hospital. About halfway through the session, she escorted me down a series of hallways to the emergency department.

“I think you need more help than I can give you,” she said as we prepared to leave her office.

She was worried because of something I had done, but I also fit a certain profile.

According to my therapist's notes, I had “multiple risk factors that include his age, his level of depression, feelings of hopelessness and helplessness, feeling trapped, known to be impulsive.”

In the emergency department, I was ushered into a small office with a triage nurse.

“Have you had thoughts of hurting yourself?” she asked after she had checked my vital signs and made some standard health inquiries.

I'd been thinking about it off and on for months. I had checked out guns online and identified a weapon that was big enough to do the job and within my budget. The day before my appointment I had gone looking for the location of a gun shop. I found it, and that morning I pulled into the parking lot, though I didn't go inside.

Instead, I went to my appointment and told my therapist where I had been. I was scared.

I was no stranger to therapy.

I had my first session when I was about 11. My mother thought there was something wrong with me because I had been acting out in school. By then, I had endured years of physical abuse at the hands of my stepfather and mother, who each battled alcoholism and struggled to raise seven kids. I was also sexually abused repeatedly by a teacher at my elementary school.

Yeah, there was something wrong with me.

I told none of that to my first therapist, but I was perpetually angry and it manifested itself in various clashes with authority figures over the years.

I argued every call on the basketball court as if the referees had it out for me personally. In eighth grade, I hit a teacher. In 10 th grade, I picked up a plastic chair and struck a staff member “about the head and shoulders,” as it said in the successful court petition to have me declared a juvenile delinquent.

By then my mother had lost custody of her children and I was in foster care. I started weekly sessions with a psychiatrist and took an antidepressant through my high school years.

I graduated from high school — probably to the astonishment of some of my teachers — and went to college. Turned out, I wasn't as bad a student as they all thought back home. I received my bachelor's degree and happened into journalism, starting in radio before moving to newspapers.

Externally, at least, I appeared fairly well adjusted. Professionally successful, I married and became a father to a beautiful, smart, funny little girl.

She brought us joy, but something seemed to be missing. For instance, it didn't seem like a huge deal at the time, but when my wife and I attended an uproariously funny movie, "Ruthless People," and people all around me were in hysterics, I walked out of the theater with the realization that I had not laughed even once.

I was devastated when that marriage fell apart after just three years. I considered committing suicide and, even worse, homicide—thoughts I shared with my estranged wife—though I never made a plan or took steps in either of those directions.

But for a couple of months while living alone I was often paralyzed by depression and an emotional pain so debilitating that there were days I never got out of bed. When I did make it down the stairs, I languished for hours on the end of my ratty little secondhand couch, wallowing in self-loathing.

Fortunately, I connected with a forensic psychologist and for nearly three years drove an hour each way from Lebanon to Concord for my weekly appointment. The worst part was that my pickup had no radio, so all I had to listen to was whatever was playing in my head. That wasn't always pretty. And for the second time in my life, I started taking an antidepressant.

The key to picking up the pieces, I discovered, was my relationship with my daughter. With my marriage over, I needed a new identity and I found it. Being Whitney's dad was not only what I was, it became how I defined myself and allowed me to keep going. I felt like she had saved my life.

I told her that story on the Saturday before I was admitted to the hospital last month, when I went to say goodbye.

When I informed the triage nurse that I had formulated a plan to take my life, I was taken to a room down the hall in the emergency room. The sign outside said it was under audio and video surveillance. It had a reclining chair, a TV enclosed in wood and plastic, and nothing else.

Pretty spartan, I thought, and I took out my phone to take a video of my surroundings.

A nice man came in — a nurse practitioner, I found out later — and asked me questions about my state of mind. I teared up when I described what I was feeling and told him about my flirtation with the gun shop.

A few minutes later a burly man in hospital scrubs came in and introduced himself as Joe. He told me he was going to stay with me and asked a series of questions nearly identical to those I had already answered. As much as I wanted to hurt myself, I told him, I was not a threat to anyone else, answering a question he had not yet asked.

Joe parked himself outside my room and for the first time in my life, I felt like I was not free to go.

I was given ill-fitting paper hospital scrubs and told to change. Security took my phone, but I was allowed to use one of the hospital's cordless phones. I called my current wife, explained where I was and why, and promised to call her back when I knew more. I can't say she was surprised.

I was waiting for a bed to open up at something called “the Annex,” which is technically part of the Lakes Region General Hospital emergency department. It's a six-bed facility where people are parked until doctors can make arrangements for patients to enter a facility and get treatment.

There is a bottleneck for people trying to access mental health treatment in New Hampshire, and hospital emergency departments are where the system backs up.

According to a July 2017 report by the state NH Department of Health and Human Services, the number of people sitting in emergency departments like the Annex while waiting for a bed to open up at an inpatient psychiatric facility averaged between 32 and 46 on any given day in the previous two years.

And there were days when that number spiked.

“The number of NH residents waiting in hospital EDs for admission to inpatient psychiatric treatment has more than tripled since 2014, exceeding 70 across the state on several days in the past year,” says the state's 10-year strategic mental health plan, which was released last month, the day after I got out of the hospital.

The reasons for that vary, according to the DHHS report, but some of the factors include a shortage of psychiatric beds and a shortage of step-down treatment sites like short-term residential facilities.

According to DHHS, the state has five Designated Receiving Facilities: New Hampshire Hospital in Concord is the largest, with 168 beds (24 of those reserved for children). The others contain only 52 beds total: Cypress Center in Manchester (16); Elliot Hospital in Manchester (14); Portsmouth Regional Hospital (12); and Franklin Regional Hospital (10).

A shortage of beds is only part of the problem. A shortage of nurses also plays a role in determining whether a bed is available. As one mental health provider explained to me, even when beds might be unfilled, if there aren't sufficient nursing staff to meet the staff-to-patient ratios deemed necessary to provide adequate care, those empty beds might stay empty on any given day.

The Annex

After a few hours sitting in the room Joe was guarding in the emergency department, I was escorted to the Annex, which had all the charm of one of those park-and-ride lots off the interstate. I had a room to myself that featured a curtain where a door might have hung, and a bed. There was a wall-mounted television and a small sink that was prison-issue stainless steel. There was no window and no bathroom. The latter was down the hall, past the nurses' station where a security guard was perched outside in case of trouble.

Not much happens at park-and-rides, and the same could be said of the Annex while I was there.

One of the nurses talked to me for about 10 minutes when I first arrived in what seemed like an attempt to take my emotional temperature. When he departed, I sat on the edge of the bed, buried my face in my hands and cried—deep, body-wracking, convulsive sobs.

As if on cue, another nurse showed up with a box of tissues and it was then that I noticed the small video camera mounted near the ceiling, next to the television box. I was under 24-hour surveillance.

How did it ever come to this, I asked myself.

The time I spent in the Annex — about 27 hours — is a mind-numbing blur of naps, meals and bad daytime TV shows, with a couple of visits from my wife as the only highlights. I had a two-minute conversation with my therapist on the second day, but no treatment took place there.

Toward the end of the first day I was informed that they had arranged a bed for me in a psychiatric facility at Hampstead Hospital, a short distance from Manchester, but they wanted to interview me first.

I spoke on the phone with an admissions person and she gave me an overview of what I could expect. I would be under the care of a team of mental health professionals, she said, and they anticipated I would be there for about five days.

That all sounded fine, but I balked when they told me I would have to be transported to the facility in an ambulance. I didn't see that coming and grew agitated, arguing that I was perfectly capable of driving myself.

My resistance to a long ambulance ride, I discovered later, was interpreted as refusal, and the arrangement was abandoned and another placement sought.

My wife Janis arrived at the Annex after she got off work. She was ushered through a security check and allowed in. She brought me a meatloaf sandwich, chips, a bag of Pepperidge Farm cookies and a bottle of tonic water. She also brought a book I had been reading. She stayed for about 90 minutes and we filled each other in on our days, which felt a little weird since mine had been so surreal.

I was sorry to see her go, grateful for the support and aware that not everyone is so lucky to have the kind of support system I do.

She was back the next morning around 8, an angel bearing a large cup of coffee.

This time, though, the nursing staff refused to allow her to bring anything into the room.

It's against the rules, we were told.

I understood the reasons behind a rule like that—some unscrupulous types might try to smuggle in more than coffee. I was annoyed, however, that nobody had mentioned that when I first arrived, and I told the nurse that Janis had been allowed to bring me food and drink the night before. The nurse attributed that to the night staff not following the guidelines, and said there would be no coffee this morning.

I tried to argue with her, but she rooted through a file cabinet in the office and returned with a set of guidelines.

“Do you want to read them?” she said sternly, thrusting out a sheet of paper.

“No,” I said, my voice rising a little. “I want this place to be consistent.”

She didn't budge, and after venting a little more, Janis and I went to my room. She was almost as annoyed as I was, but we put it behind us and talked about happier things for a half hour. She then headed off to work in Laconia and I went back to the mundane existence of life in the Annex.

Other than the visits from Janis, the only non-staff interaction I had at the Annex occurred when I took a seat in the dayroom and watched The Weather Channel's coverage of the storm that was dropping snow on New England. Watching TV from a different location actually felt like a change of scenery. Plus, it felt good to sit upright for a few minutes.

A woman who seemed to be in her 30s came out of the bathroom and stopped to look at the television.

“I used to live in Massachusetts,” she said when she noticed the reporter was broadcasting from there.

She wore the same kind of paper scrubs I did and looked tired, her thick blondish hair pointing in every direction. Nobody looks good at the Annex, apparently.

“Annie,” (not her real name) the nurse called out from the station nearby. “You know you're not supposed to talk with other patients.”

It was not her first stay at the Annex, I learned later when I met up with her in Franklin.

My case, in nonmedical terms, was “a can of corn”—an old-fashioned baseball term for a lazy fly ball that is easily caught by an outfielder.

The technical diagnosis, according to my psychiatrist's notes, was “adjustment disorder with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct.”

The nurse practitioner who examined me recorded “Depression F32.9” in my records, meaning it was a single episode of major depressive disorder, unspecified.

That, in a way, was good news.

Designated Receiving Facility

The fact that mine was a straightforward case of depression meant that, rather than languishing in the Annex at Lakes Region General Hospital for days, I was an easy “yes” for mental health facilities with open beds. My case wasn't complicated by addiction and I had no history of violence (my juvenile transgressions weren't part of any record). If those had been factors in my case, that could have narrowed the options available to me, I was told by a practitioner, since not all facilities treat patients with addiction and some lack the security features needed to deal with patients who might be prone to violence.

In this case, the “yes” came from my insurer and from Dr. Raymond Suarez, who runs the Designated Receiving Facility at Franklin Regional Hospital, where I arrived by ambulance late on Wednesday.

The early notes from the nursing staff record that I stayed in my room a lot in the beginning and describe me as “standoffish” and a “gentleman.” They also state that I was prone to rapid mood changes, sometimes confrontational and had poor coping skills and a hard time concentrating on a single subject.

Those assessments are accurate, I think, and speak to the fact that there was little that escaped the notice of the nursing staff. For instance, when I was given permission to ditch my hospital scrubs, I was impatient when my regular clothes weren't ready, something mentioned more than once in my file.

My room had a desk and a chair and a real door with a window. While I lay in bed at night waiting to fall asleep, I noticed a shadow passing over the window at regular intervals. It was one of the nurses doing a well-being check.

There were five of us at the table for breakfast on my first full day on the unit, and we ate as the nurses made the rounds to hand out meds. The nurse assigned to me gave me the dosages I regularly take for high blood pressure and elevated cholesterol, then gave me another pill with a name I didn't recognize.

“I don't have a prescription for that,” I said.

He told me it was Lexapro, and Dr. Suarez had prescribed it for me.

I stood up quickly, an act his notes indicate he interpreted as a sign of aggression.

“I'm sorry,” I said, “I may be a little old-fashioned, but I think the doctor should actually see me before he writes a prescription.”

He told me I didn't have to take it, and I replied that I wouldn't. The notes also indicate that I apologized for my hostile attitude, though I don't remember that part.

The prescription was a bone of contention when I met with Dr. Suarez and the treatment team later that morning. The team included the nurse assigned to me, a nurse manager, and a couple of social workers.

To his credit, Dr. Suarez let me vent about the prescription. I repeated my objection to being given a script sight unseen, and argued that I should have at least been informed or consulted before it was written and given to me.

He said he had written it after reading my file, and felt it was the right medicine for me.

“Why are you angry?” he asked at one point.

His notes report that, “Patient's anger at the issues stem from a previous interaction with a psychiatric that he felt did not give him enough time prior to diagnosing him and giving him a medication.”

He was right. I told him about a psychiatrist who had once — wrongly — diagnosed me with bipolar disorder after meeting with me for just minutes.

I spent about 45 minutes with the treatment team and returned to the unit feeling better and agreeing to take the Lexapro.

Like the other patients, I had meetings like these every day I was there. I came to look forward to them. I felt supported and the sessions allowed me to get feedback on my progress.

“You're going to be OK,” Dr. Suarez assured me on Friday.

I was a can of corn.

Group

Daily life at the Franklin Designated Receiving Facility (DRF) revolved around a robust schedule of group therapy, or “group” as it was called. I was given a schedule of group sessions when I first arrived, along with a set of guidelines that said everyone was expected to participate.

The first group was a session about the importance of staying hydrated.

Others were more substantive: crisis prevention and management; four dimensions of recovery; coping with stress; the cycle of anger; recognizing protective factors in your life; building social support; battling depression and anxiety; negating negative self talk; boundaries and the end of hopeless/toxic relationships; building social support.

The goal, as I understood it, was to come up with a self-help plan for recovery.

I attended all of the groups, though not everyone did. Some patients slept instead—a lot.

And sometimes a scheduled group session wasn't held for some reason, in which case we stayed in our rooms, hung out with each other in the dayroom or used the time to shower. Several patients colored with markers for hours on end. They worked on sheets of black and white coloring paper that included inspirational sayings and images. One featured a dream-catcher with feathers and the words, “Only an open heart can catch a dream.”

Even those who barely participated in group sessions found coloring therapeutic, and a bulletin board within the unit was decorated with patient art.

Coloring wasn't my thing, but the groups were helpful exercises in self-reflection and offered the opportunity to receive support from other patients, who all seemed aware that everyone there had fairly tender sensibilities. A lot of encouragement and praise passed between us, though there were the inevitable conflicts, too. One patient seemed to take a particular dislike to another, and lashed out more than once, upsetting our delicate group balance.

That, however, was the exception, and I came to like and respect all of my fellow patients. I also made a conscious effort not to pry into the circumstances that brought us together, figuring they would share what they felt comfortable with.

It was impossible to tell who was there for what without being told. One woman, bright, creative and funny, was clearly struggling with a loss. Another said she had spent nine days in an emergency room after she tried to kill herself with a heroin overdose. She had hoped to be admitted again to New Hampshire Hospital, the state's largest psychiatric facility with 168 beds, but was sent to the 10-bed Franklin facility instead. She was not happy about it.

No secrets

I, on the other hand, was never happier during my stay than on Saturday, when I expected a visit from my daughter and her fiancé. Of greater importance to me was the fact that they were going to bring my granddaughters, ages 9 and 7.

A staff member had assured me earlier in the week that it would be OK for them to visit, but during a Saturday morning meeting with the psychiatric nurse practitioner, she said it was contrary to the rules to allow visitors under 18.

She posited several reasons why they shouldn't be allowed to visit. It might not be appropriate for the children, she said, and there were concerns about patient privacy.

I felt myself growing frustrated, but tried not to get angry. I countered that it should be left up to their mother to decide what was best for the girls; and as for privacy, who were they going to tell?

“They know where I am and they know why I'm here,” I said. “We don't have a lot of secrets in my family.”

It was important for the girls to see that Grampa was OK, I continued. And not only that, it was important that they see me in this environment, so they know that it's OK to ask for help when you struggle.

I felt like the very system that seeks to remove the stigma surrounding mental illness was perpetuating that stigma by treating mental health care as something to be hidden from children.

I had a vision of going to visit my mother when she was institutionalized at New Hampshire Hospital in the early 1970s, when we were only allowed to see her through a small window in an external door at the end of a hallway. We stood outside and waved to her, and some of my siblings cried.

The practitioner said she would consider my request and let me know.

Great, I thought as the meeting broke up, as long as the answer is yes.

In the end, it was. She consulted with Dr. Suarez, who gave the OK to let the girls visit.

As I walked up the hall toward the locked doors that led to the visiting room, I received words of kindness and encouragement. The other patients were happy for me and knew how much the girls meant to me.

I passed through the doors just as the security guard finished patting down my future son-in-law. The guard then turned to the two little girls with flowing long brown hair.

“Do you have anything in your pockets?” he asked with a smile.

They shook their heads, and he gave them permission to enter the visiting area. I was grateful the guard had the good sense and decency not to subject them to a pat-down.

Bad Meatloaf

The visit started out with hugs and small talk and, after a period of time, I asked the girls why I was there.

“Because you're sad,” Gracie said.

“That's right, sweetie,” I replied. “It's called depression and it happens sometimes. And when it does, it's OK to ask for help.”

I told them the doctor said I was going to be OK.

Then I joked that I was in the hospital because of a bad reaction to bad meatloaf.

They laughed, but there was a kernel of truth to it, too.

My meatloaf has always been their favorite, and they ask for it every time they come for a sleepover, which is about once a month. One of the joys of making it has been involving them in the preparation. They crack the eggs, add the bread crumbs and liberal amounts of ketchup (the secret ingredient) and spices. Then they dig their little hands into the ground beef and mix it all up before spreading it out in a cake pan and glazing it.

The plan when they visited me the previous Sunday in Laconia—the day after I had gone to say goodbye to their mother—was to make meatloaf, steamed broccoli and boxed macaroni and cheese.

Maddie, the 9-year-old, begged off, so Gracie and I flew solo in the kitchen.

“Is this enough ketchup?” she asked, holding the squirt bottle upside down.

“That's fine,” I said, barely looking at the mixing bowl.

The depression had hit the day before like a tsunami, washing away thoughts of all of the things that normally brought me joy and leaving me feeling isolated and hopeless.

I managed to get the meatloaf in the oven, but everything after that seemed overwhelming.

“Janis?” I called, and she came down the stairs and knew immediately that I was in a bad state.

She flew into action and we soon had broccoli and mac and cheese on the table.

The meatloaf, however, was easily the worst batch ever.

In other words, it was a reflection of my mindset. I had been there physically but not mentally, and two days later I was in the hospital.

Now the girls and I joked about the meatloaf, which they admitted was horrid. More importantly, for 45 minutes I was able to live completely in the moment in a way I hadn't done for weeks. I felt normalcy returning.

I hugged everyone goodbye and walked through the adjacent doors to the unit, where I saw the most uplifting sight.

Patients were in the hallway looking toward the external doors—like heads popping up in a prairie-dog village—hoping to catch a glimpse of my little treasures as they were leaving. It was further affirmation of just how lucky I was, a sensation I also experienced that night when I hugged Janis in the hallway as she was leaving. The other patients cooed and ooohed and aaahed.

Discharge

The group sessions and antidepressant worked and my outlook improved quickly. I was discharged Monday and returned the same day to my job, where I explained my situation to my boss and co-workers and was met with support. Everybody should be so fortunate.

I honestly don't know if I would have killed myself. Given more time, I believe I probably would have bought the gun. After that, I think, it would have been a coin flip.

Instead, I sought help. I hope others in distress do the same, because help is out there.

My discharge from the psychiatric unit was not the end of my journey.

As a friend of mine said recently, “introspection is the heaviest of lifting.” I still have work to do. I continue to see a therapist, and a psychiatric nurse has been added to the mix, but I believe I'll come out the other end in good shape.

I decided to write about the experience for the same reason I wrote in 2015 ( https://tinyurl.com/y9coenrk ) about being physically and sexually abused: Because not talking about a subject doesn't make it better.

The National Institutes of Health estimates that one in five Americans has a mental illness, but only about half seek treatment, many because they are afraid of being stigmatized.

With numbers like that, we all know someone afflicted with mental illness, so ask yourself who you'd rather live or work next to: someone who knows they are struggling and gets treatment, or someone who doesn't?

It's in everyone's interest to remove the stigma that exists around mental health care.

I also decided to write about it because I agree with a movement started by former New Hampshire Supreme Court Chief Justice John Broderick, who has said we should end the stigma and make symptoms of mental illness as well-known as the signs of a heart attack or stroke. Talking about it openly and honestly is the best way to do that, and I've tried to do that while also protecting the privacy of those I encountered along the way.

Click here to watch a video of Roger Carroll discussing his experience.

Where to Get Help

https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/dcbcs/bbh/

https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/dcbcs/bbh/centers.htm

https://www.dhhs.nh.gov/dcbcs/bdas/

Current Issue - April 2024

Current Issue - April 2024