It could have been a lot worse.

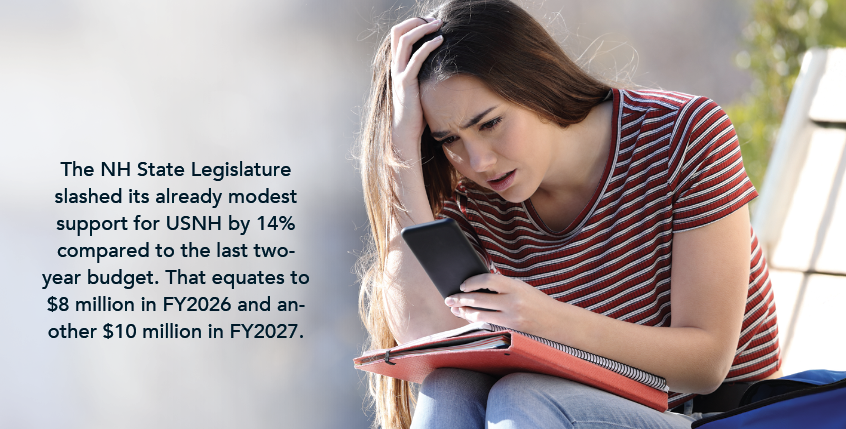

That’s how supporters of the University System of NH (USNH) view the recently concluded session of the state Legislature, which slashed its already modest support for USNH by 14% compared to the last two-year budget. That equates to $8 million in FY2026 and another $10 million in FY2027.

The House of Representatives, which got the first crack at the budget in early 2025, shocked university officials with a spending plan that reduced support for UNH, Plymouth State and Keene State by 30%.

“We had parents who said their child wanted to go to one of our institutions but decided to go elsewhere because of the press around those cuts,” says USNH Chancellor Catherine Provencher. “They worried that the programing is going to suffer, that supports for students are going to suffer.”

When the Senate got its turn, it passed a measure calling for a 10% reduction in USNH support. Finally, Gov. Kelly Ayotte proposed a 4% cut, which would have cut state funding from about $95 million a year to $91 million.

On June 26, with time running out on the 2025 session, the governor, Senate and House members on the Committee of Conference agreed to $87 million for year one and $77 million for year two—a 14% reduction.

Senators promised that if revenues come in higher than expected, an amendment will be submitted to increase year-two funding.

The fact that a 14% cut was greeted with relief shows the kind of environment university officials have been working in for well over a decade. And now, their woes are even greater as a combination of anticipated reduced federal funding and lower than anticipated fall enrollments increased the gap between revenues and expenses by $8.2 million.

Never Fully Recovered

Funding for USNH in fiscal years 2009 and 2010 was $100 million for each fiscal year. As the recession devastated state revenue, USNH funding was cut in half, to $50 million per year in the following biennium. The university system has been clawing its way back ever since.

“There were comments from House members when the House passed its 30% cut that the system managed to sustain a 50% cut in 2011,” says Provencher, explaining those deep cuts forced tuition hikes of 19.5% in year one and 13.5% in year two. That kind of reliance on tuition is no longer an option.

“We are increasing [tuition] 2.5% after being flat for six years,” says Provencher. “We’ve looked at price sensitivity, asking could we go up a little further? And the answer is ‘no.’ The students won’t come. There is so much competition. Our goal is to keep students here because they are more likely to stay and work here after they graduate.”

Additionally, the competition for students has become cut-throat. “Our surrounding states are doubling down,” says Provencher.

UMass Lowell is offering in-state Massachusetts tuition within a 50-mile radius of its campus, a geographic area that includes much of Southern NH. The University of Maine system is offering the equivalent home-state tuition to students from New England, New York and New Jersey. In other words, if you live in NH and go to UMaine Orono you will pay NH in-state tuition rates. If you live in southern NH and go to Lowell, you will pay in-state Massachusetts tuition, which is lower than the in-state NH rate.

Demographics Force Changes

Higher education throughout the country, but particularly in New England, is undergoing a transformation that will force many institutions to shrink or even disappear over the ensuing years because there are fewer college-age students and many are opting for trade schools, community colleges or direct entry into the workforce.

“You can see it in K-12 enrollment,” says Provencher. “There are fewer 18-year-olds. It’s demographics. Our enrollment has declined because of those demographics. In addition, the market competition in New England is intense because there is a college on every street corner and all are competing for a smaller pool of students.”

College enrollment nationally grew 3.2% in spring 2025 compared to spring 2024, but it remains below the spring 2020 level, according to research by The National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. At the same time, enrollment in vocational two-year colleges grew 11.7% in spring 2025 compared to the previous year, with overall enrollment 19.4% higher than in 2020.

University officials are clear-eyed about the consequences. Melinda Treadwell, president of Keene State College, says her campus had to cut expenses significantly for years and expects the trend to continue. Keene State faced significant budget shortfalls in the years following the COVID pandemic.

“I was hired to address a structural [budget] gap,” says Treadwell, a Keene State graduate (Class of 1990). Treadwell says the college turned around financially by examining its administrative cost structure and how the non-student facing experience can be made more efficient. “Can we do some things to reduce our compensation as a system? Can we use the buildings in new ways than what we have in the past to reduce our cost structure?” she says of the questions they asked.

Essential to Cut Costs

With student enrollment and state support down, and projected losses in federal funding, higher education will require significant restructuring in NH and elsewhere to remain sustainable.

“Last fall at our board retreat we did modeling out to 2030 and understand we need to take $50 million out of our cost structure by 2030,” says Provencher. “We’ve already reduced faculty head count, part-time and full-time staff head count, reduced contributions to retirement plans, reduced medical benefits and increased premiums. We’ve sold buildings, we’ve demolished buildings, we’ve eliminated expensive leased space.”

And that’s just the beginning of a significant reduction in the university system’s “footprint,” according to Provencher. “When enrollment drops 20% over 15 years, we have to reduce the footprint,” she says. “We need to continue to sell assets or downsize and get a revenue stream from that.”

Amid all of this downsizing, the university system is working to retain the programs and student experience that have historically drawn high school graduates from in-state and out-of-state to UNH and its sister campuses. The state’s economy literally depends on it.

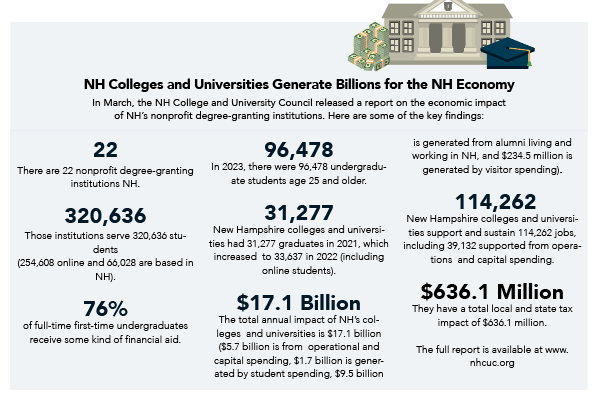

“New Hampshire’s higher education system is a cornerstone of the state’s economy, contributing $7.6 billion and supporting almost 52,000 jobs,” according to a report released in May by the NH College and University Council (See sidebar). According to Mica Stark, president and CEO of the council, the numbers are based on operational spending by the institutions, student spending and visitor spending.

That impact, along with the critical role NH’s colleges and universities play in the workforce pipeline, has attracted increased support from the business community. “We now have a broad coalition with members of the business community advocating for higher levels of state funding for the university and community college system, and the only existing state-funded scholarship program,”

says Stark.

That coalition has an easier sell when it comes to the community college system, with the House, Senate and governor all proposing increases to community college state funding ranging from 9% to 12%.

“Ultimately only policymakers can answer why the community college system allocations have gone up while the university system allocations are coming down in this budget cycle,” says Nicole Heller, a senior policy analyst at the NH Fiscal Policy Institute. “But I can speculate generally that there is a perception that community colleges more directly impact workforce outcomes related to trades and upscaled workforces as well as being a more affordable way for students to start their college careers, even in high school through dual enrollment.”

The increase in funding for the community college system is slight—$500,000 extra for the dual enrollment program. “The funding in the budget bill that passed today is roughly comparable to the prior biennium, with the primary exception that the budget passed today increases funds to CCSNH for the dual and concurrent enrollment program, raising the funding from $2.5 million annually to $3 million annually. This is the program that enables New Hampshire high school students to take courses for dual high school and college credit. More than 10,000 high school students take advantage of this program each year, getting a significant head start on college coursework, saving money on college tuition, and gaining career preparation. (In fact, a number of students this year earned a college associate degree at the same time that they graduated from high school thanks to this program),” states Shannon Reid, executive director of government affairs and communications for the Community College System of NH, in an email.

“While flat funding does come with challenges, CCSNH nonetheless recognizes the many competing and compelling needs before budget-writers this year, and we appreciate the level of support the Governor and Legislature were able to include for the community colleges and the students, industries and communities we serve, “ she states.

A Variety of Needs

Four of the 10 occupations with the largest projected 10-year growth and three of the top five are in fields that require college degrees, according to a workforce assessment published by the NH Department of Business and Economic Affairs, last updated in 2023.

“A robust workforce has a variety of different training needs,” says Heller. “Some need four-year degrees, some post-secondary training. In any state there needs to be a variety of training levels available to make sure our workforce is knowledgeable in the occupations most in demand.”

Keeping that variety of programs in place despite shrinking resources is the challenge facing higher education across the country. Funding is also unpredictable at the federal level with changes at the National Institutes of Health and other major grant sources.

President Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill” includes reductions in Pell Grants for low-income students, while NH lawmakers froze funding for the UNIQUE program that provides state-funded higher education grants for students who demonstrate exceptional financial need.

“The challenge for the Granite State is our state level of contributions to higher education is the lowest in the country,” says Heller, “so financial constraints are more likely to fall on students and families.”

_Alex-and-Jason-in-front-of-map-sm.jpg)