Alexx Monastiero, a land development specialist with the Gove Group in Stratham, is among the many stakeholders in the housing industry carefully tracking the progress of zoning-related bills at the State House.

The past session saw an explosion of legislation designed to address a severe housing shortage in the state. Most bills were aimed at narrowing the ability of municipalities to restrict growth by what some call unreasonable zoning and building codes, otherwise known as “snob zoning.”

“None of these bills are a silver bullet,” says Monastiero, “but that doesn’t mean we should do nothing. All of these bills in their own right will contribute in some way to increasing opportunities for housing solutions.”

There is a critical need to find those solutions, according to housing advocates across the spectrum, because the state’s financial future is at stake. Without affordable housing, NH will not attract and retain a young to middle-aged workforce, resulting in an aging population on fixed incomes, fewer working families and a shrinking economy.

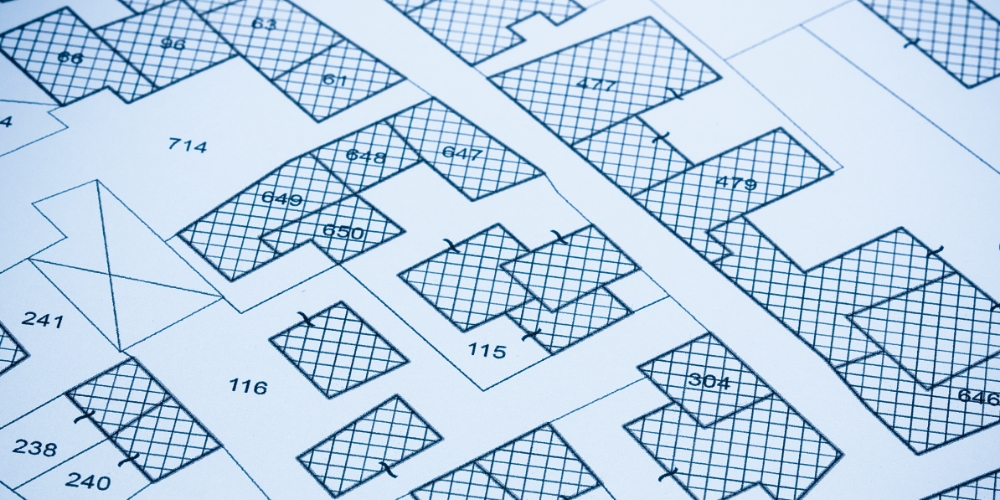

The problem is graphically illustrated on the New Hampshire Zoning Atlas, a project spearheaded by St. Anselm College, which uses the color purple to designate areas of the state where single-family homes on small lots of less than 1 acre are prohibited. The state is awash in purple.

“Looking closer at the data, it is hard [in NH] to find land to build small homes or starter homes in an economically viable way. Most communities have prohibited single-family homes on small lots (less than 1 acre, less than 200 feet of road frontage). Only 15.7% of the state’s buildable area allows for (small lot) development,” according to the narrative with the map.

“The state is in a housing crisis, and if the state does not act and put some guardrails for the towns to work within, then it’s going to be too late. People are not going to be able to stay in New Hampshire. They’re not going to be able to buy a home in New Hampshire,” says Monastiero.

A 2016 graduate of UNH, she and her husband bought what she called an affordable house in Rochester in 2018. “People are not going to have that opportunity again, and it’s going to be too late, and we’re going to have to play catch up,” she says. “All of the young people will have moved out of the state. All of the people who are 40 and older got to buy the last home in their town, and now they get to say no more in my town, nobody else gets to build an affordable house here, and then there won’t be any workforce.”

A Different Perspective

The NH Municipal Association (NHMA), which represents the 234 cities and towns in the state, sees the situation differently, as do the many planning board, zoning board and select board members who testified against the legislation.

In a recent newsletter to members, NHMA Executive Director Margaret Byrnes wrote that the Legislature is taking a “blame local government” approach to the housing shortage.

“As a result, there are dozens of zoning mandate bills, some of which conflict with one another and many of which are poorly drafted, vague, and conflicting with current statutes and none of which actually incentivize or require the development of affordable housing, despite them being promoted as housing bills.”

Bills that passed both the House and Senate to address everything from parking space requirements to attached dwelling units are misdirected, according to

the NHMA.

“We don’t think inventory is a problem,” says Byrnes. “We see there are developments, apartments, condos and huge homes being built to be sold at the rate the market will support and that rate is often over what the average person who is looking to buy can afford.”

“We see developers building what maximizes profit, as is their prerogative to do. But blaming local zoning is an easy narrative that doesn’t cost the state any money and doesn’t require us to confront the other factors driving affordability and housing stock. Instead of problem solving, it’s problem shifting,” according to Byrnes.

No Financial Support

Housing advocates and the municipal association agree on one thing: The state is not spending enough money to encourage affordable housing. They point to the Housing Champions program, which offered incentives to communities that are receptive to housing, like funding for utilities and other infrastructure. That program was defunded as lawmakers tried to balance the budget.

The bill that housing advocates believe would have the most impact is SB 84, regulating lot sizes, which was retained in committee and could come up again next session. It would still allow for 1-acre minimum lot sizes, but not the 2-, 3-, or even 10-acre minimums some communities maintain for certain rural zones.

“There’s no question that if we are going to resolve the current housing shortage, we are going to have to confront this issue of large lot requirements, which are a significant contributor to the unaffordability of housing in New Hampshire,” says Bob Quinn, CEO of the NH Association of Realtors.

Large lot sizes and high land prices aren’t the only forces constraining inventory. The Great Recession took a huge toll on the homebuilding industry as companies went out of business and trained workers went into other industries. The sale of existing houses has plummeted because aging boomers have no place to move and are sitting on low-interest mortgages.

New Building Collapsed

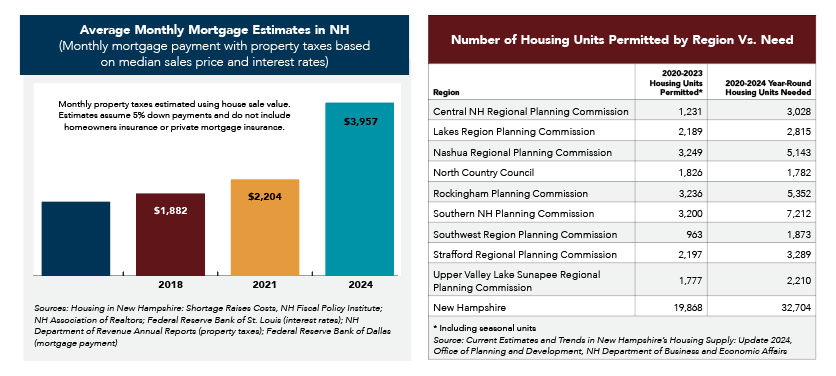

Twenty years ago, municipalities in NH collectively issued more than 9,000 residential building permits. That number started to dip in 2006, bottomed out in the Great Recession at 2,000 permits, and never fully recovered. The number of permits issued in 2023 was below 5,000.

In 2005 the median priced home was about $260,000 while median family income was about $58,000. Today the median home is $540,000 and median household income is about $100,000.

The gap between earnings and housing costs is the largest it’s been since the NH Board of Realtors began measuring affordability in 2005. The state’s median household income is just 56% of what is necessary to qualify for the median-priced home under today’s interest rates.

The only way to move the needle in the other direction, according to the broad coalition of housing advocates represented by Housing Action, is to increase inventory across the state. Quinn points to research by the NH Department of Business and Economic Affairs showing that one-third of all residential permits issued annually are consolidated in eight to 10 communities.

“The only way that we are going to resolve the housing crisis in New Hampshire is to have every community contribute,” he says.

No Agreement on Solutions

The public is ambivalent about solutions. Polling shows that when questioned on each housing bill separately, respondents show majority support. But when asked generally whether the state should restrict local zoning options, the majority response usually favors local control.

“Change is hard and when you start to get into some of the more technical issues, there’s an increased likelihood of misunderstanding or a reluctance to act at all,” says Nick Taylor, director of Housing Action, a coalition of more than 120 nonprofits, banks, community organizations, developers and other stakeholders coalesced around the issue.

“So often what we hear is a lot of concern around water, sewer and septic capacity. But none of these bills would override DES [Department of Environmental Services] standards. None would require a town to issue a permit if they don’t have the water and sewer to deal with it.”

The infrastructure argument is often a straw man for the real concern, valid or not, that increased density will decrease property values.

“We hear it all the time at the Statehouse, the belief that new housing might impact my property values; it may create a situation where kids come into the town and they need schools and we have to educate them and my taxes will go up,” says Quinn, who is also the director of government affairs for the realtors.

“On the House floor we’ve heard reps argue that multi-family creates more crime, more drugs. It’s this fear of the unknown. But none of those things are true. All have been explored thoroughly and found to have no validity, yet they persist even after you present people with this data and evidence.”

Disproportionate Burden

Byrnes maintains there’s nothing inherently wrong with restricting higher density housing to the state’s population centers.

“Developers want to build in areas that are hubs for business and employees, with public water, sewer and other key infrastructure like easy access to highways and sufficient parking,” she says, arguing it simply makes sense for the bigger, more developed places to take on the lion’s share of new housing. Accepting the status quo will never lead to meaningful solutions, says Matt Mayberry, CEO of the NH Home Builders Association. “It’s a statewide problem, not a regional problem, not a municipal problem,” he says. “It’s not fair to expect Manchester to provide solutions while Bedford pulls up the drawbridge and says we don’t want those people in our town; let Nashua, let Manchester deal with it.”

_Alex-and-Jason-in-front-of-map-sm.jpg)