"Let me be clear: I’ll veto any bill that imposes an income tax and threatens the #NHAdvantage. Not on my watch!” That was a tweet Gov. Chris Sununu sent out in March as the battle over the state budget began to heat up.

It is a battle cry that has been sounded by countless NH politicians over the years—a vow to never relinquish a tax environment that makes NH one of only two states in the country that don’t have a sales or income tax. (The other is Alaska, which banks on the oil industry.)

As much as the state motto, “Live Free or Die,” that unique tax structure is part of NH’s identity. As the governor points out, it is touted as the “NH Advantage” and tops the list of reasons companies move here. It is also why NH politicians generally steer clear of suggesting a broad-based tax if they want to win.

Some might even say that living in NH requires fealty to an antitax dogma. But labeling NH as a no-tax state is somewhat of a misnomer—as anyone who owns a home or business will tell you.

The NH Difference

This craggy corner of New England continually ranks high in quality of life and, based on average incomes, is one of the wealthiest states, with less than 8 percent of its approximately 1.3 million residents falling below the federal poverty line.

Despite its prosperity, or perhaps because of it, NH legislators are also well-honed penny-pinchers, who resist imposing any broad-based taxes.

The Concord mantra is spend conservatively; manage with less.

Such was the battle cry, or bombastic drawl, depending on your point of view, of the legendary Meldrim Thomson Jr., the Granite State governor from 1973 to 1979, who was a trenchant promoter of anti-tax tenets that continue to infiltrate GOP politics. Thomson passed away in 2001 at age 89, but even into his last decade, he opined to reject federal funds and encourage local control as a conservative columnist for the NH Union Leader.

“I have fought the holy cause of liberty against the sinister encroachments of the federal government,” he wrote in his 1979 book, Live Free or Die.

And while many question the wisdom behind these stake-in-the-ground polemics, no one seems to want to move the needle. “Politically, it’s considered a hot potato,” says Democratic state Rep. Susan Almy of Lebanon. “We haven’t been able to do anything for a long time.”

Almy says the last major tax reform pre-dated Thomson’s decrees. In 1970, Gov. Walter Peterson wanted to eliminate NH’s taxes on machines and inventory at manufacturing companies, the backbone of NH’s economy. He proposed taxing companies’ earnings, and when his bill passed, it became the business profits tax (BPT).

Peterson also proposed a 3 percent income tax, but didn’t garner enough supporters. By 1972, Thomson’s “Ax the Tax” campaign won over voters, who eventually ousted Peterson from the governor’s office.

In NH, the pledge to fight any broad-based taxes “is like a religion” and is integral to the state’s identity, says Lucy Dadayan, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute, a nonprofit research organization based in Washington, D.C., that provides analysis of complex social and economic issues.

Many argue that NH’s thorny self-reliance and Yankee ingenuity are what attract people to move here. They come for the landscape laden with trees and mountains, and housing that’s affordable, at least when compared to its close metropolitan neighbor of Boston. They like the antitax culture very much, thank you. And they don’t like meddlers.

Nonetheless, Dadayan says most economists argue that states need to have a diversified, progressive tax structure less reliant on a single source of revenue like property taxes. Because what happens when home values decline? Local policymakers must choose between offsetting a shrinking base with higher tax rates or decreasing budgets for essential services. Or, they investigate other methods of generating revenues, such as NH’s attempts to expand gambling.

While casinos have never been sanctioned here, supporters of expanded gambling haven’t lost hope, despite more than two decades of trying. In December 2017, NH legislation established KENO 603 to fund full-day kindergarten. KENO allows players to choose one to 12 numbers to play, wagering $1 to $25 per game. If their numbers match the 20 randomly selected ones displayed in the game, they win. Communities must vote to allow the game, so during the past year and a half, 66 communities approved it, and more than 160 establishments offer it statewide. Since it launched, KENO sales have totaled nearly $25 million, and as of March 2019, sales had already surpassed $16 million, according to the NH Lottery, which anticipates that the game could generate as much as $9 million in annual net profits.

More recently Gov. Sununu inched closer to legalizing gambling when in his 2019 budget address, he suggested that NH go “all in and get it done,” to allow sports game betting. Sununu said the betting would bring in more than $10 million in revenue for education.

Dadayan says while opposition to a sales or income tax has “become like gospel” for state officials, “perhaps it’s time to take the tough road and explore options for having a more broad-based, more diversified, and more progressive tax structure.”

Such a stance would run afoul of the Business and Industry Association (BIA), NH’s statewide chamber of commerce, which opposes an income or a sales tax as one of its legislative priorities. Jim Roche, president of the BIA, says while introducing a broad-based tax may provide temporary property tax relief, eventually politicians will burn through that additional revenue and taxes would again increase. “State and local officials have to live within their means like the rest of us do,” he says. “I would hate for New Hampshire to become another high-cost, overregulated state.”

Blasphemy in NH

Simply broaching the subject of an income tax is like drinking political poison. Just ask Jackie Cilley, a former state representative and senator from Barrington. In 2012, she refused to oppose any broad-based taxes and lost the NH Democratic Gubernatorial primary nomination to Maggie Hassan, who pledged not to introduce new taxes.

Cilley says not taking the pledge wasn’t her campaign’s biggest mistake. Her bigger regret is not clarifying a vision for NH: a state that raises the right amount of revenue in the right way to draw a young, educated and diverse workforce. The only way to achieve that, she says, is with more state support for public universities, K-12 education, good roads, well-staffed fire and police departments, and social services for the elderly, the poor, the disabled and veterans.

By not “putting out a welcoming mat for a variety of folks,” says Cilley, residents who can’t afford a public university or can’t obtain services for a disabled child move away. New Hampshire is then left with a terrain that is far grayer and poorer than its potential, she says.

Funding NH

In FY 2016, property taxes accounted for 15 percent of all tax revenue (which includes the locally raised and retained statewide education property tax), and 99 percent of tax revenue at the local level, according to the NH Fiscal Policy Institute (NHFPI). The two major business taxes, the BPT and the business enterprise tax (BET), composed 27 percent of the state’s revenue.

The BPT is a modified corporate income tax, and the BET requires most organizations to pay a small percentage of compensation, interest, and dividends paid or accrued. The two taxes complement and interact with each other, as the BET has a much lower rate but draws from a broader and less volatile base than the BPT.

Municipalities rely on statewide education property taxes to support local schools. In recent years, this tax accounted for about 10 percent of statewide property taxes, although its resources are declining. Begun in 2005 to collect $363 million a year, it has not been adjusted for inflation.

Since the state’s share is often insufficient, cities and towns need to make up the difference in property tax revenue to provide a constitutionally adequate education to their local schoolchildren. For lower income towns, this revenue is often 50 percent of the overall budget, leaving the remaining 50 percent to cover services such as police, fire, street cleaning and plowing.

In addition to state property and business taxes, the government relies on a range of more narrowly based taxes, fees and other revenue streams. While folks can shop in NH without paying a sales tax in stores, they do contribute to NH’s coffers when they eat at restaurants, stay at hotels, transfer real estate, fill up with gas, or register their automobiles.

Some of these fees, like the levies on communication services and tobacco, are declining, creating challenges to the revenue system, says NHFPI Executive Director AnnMarie French.

How big is NH’s reliance on property taxes? Consider this: Nationwide, 31.5 percent of state and local tax collections came from property taxes in 2016, more than any other source of tax revenue. That was the last year of available data, according to calculations from the Tax Foundation, an independent tax policy nonprofit. In contrast, that percentage is twice as high in NH, at 65.7 percent, and is a bigger slice of the pie than in any other state in the country.

Not surprisingly, the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy reports that NH’s property taxes siphon a larger share from individuals’ personal incomes than from any other state.

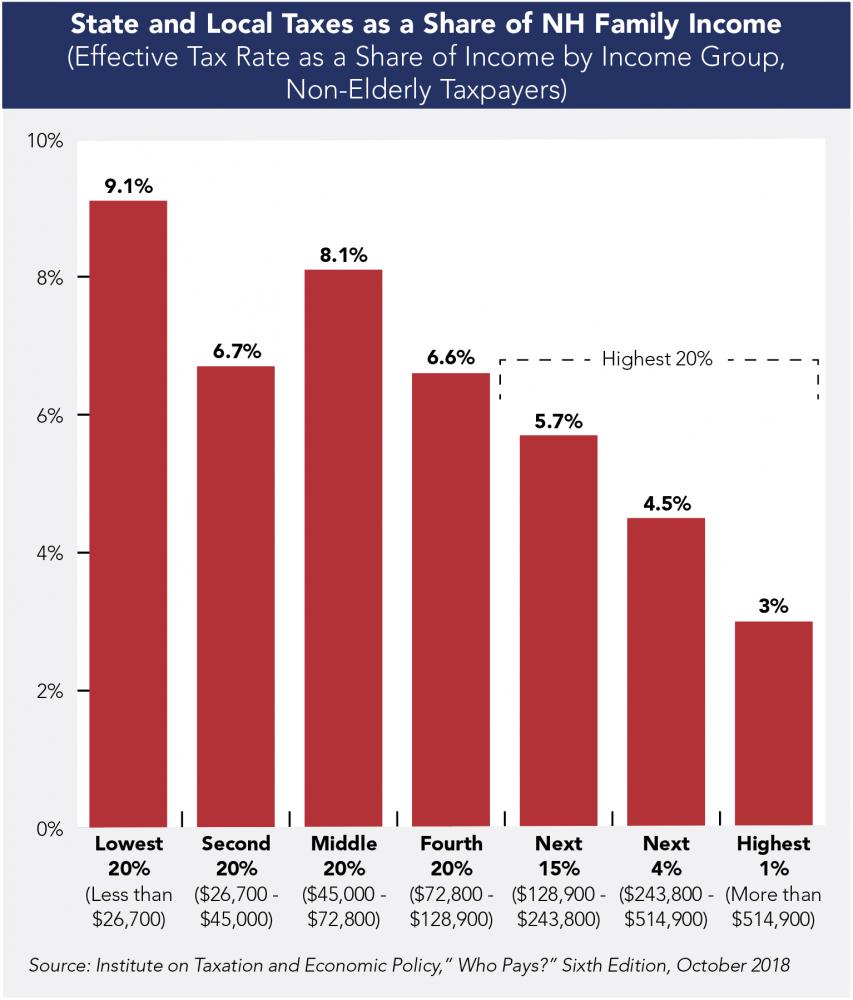

Lower-income families are carrying the tax burden for the rest of the population. Those among the 20 percent earning the lowest income pay 6.2 percent of their income in property taxes. The highest 1 percent is contributing only 1.9 percent of their incomes.

Additionally, the reliance on property taxes can pit the elderly, who face losing their homes, against families fighting for better schools. Towns are sometimes forced to choose between schools and other needs such as police and fire stations.

This drives some communities to restrict multifamily development, leaving the state without sufficient workforce housing.

One way NH cuts corners is by shifting responsibilities to local towns, says French. Consider the state’s employee retirement expenditures, for example. For almost three decades, the state contributed 35 percent, but between 2009 and 2011 it was lowered, and in 2013, eliminated altogether. In the past 15 years, towns and cities tripled what they pay into the system. (A bill, HB 497, could change this.)

Another example is the meals and rooms tax distribution. The reasons behind this are complex, but in a report from the NH Municipal Association on state aid to cities and towns, the municipal share of this tax dropped from a high of 29 percent in fiscal year 2010 to 21 percent in fiscal year 2019.

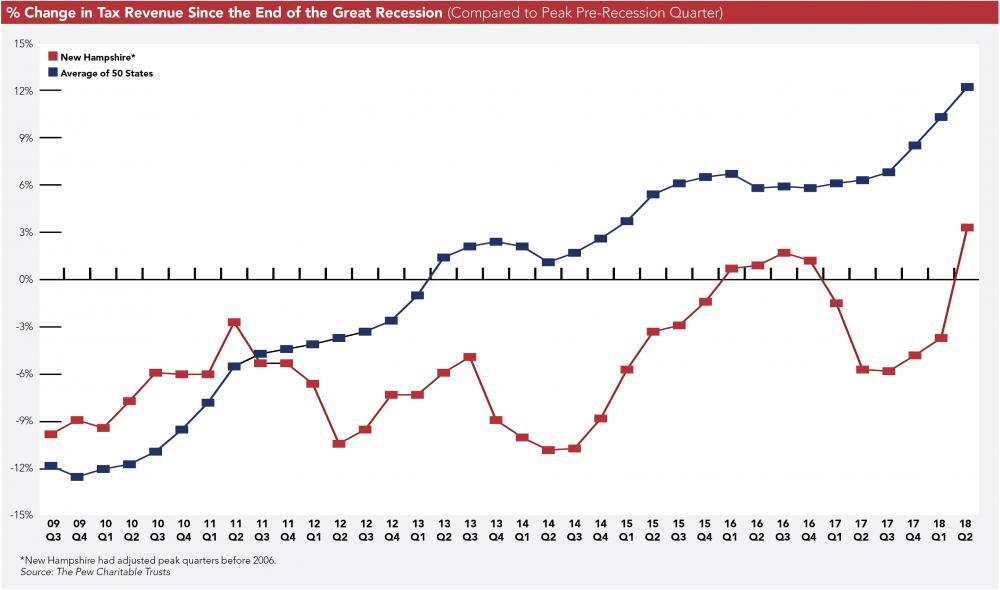

Meanwhile, state collections are on the upswing, as they are in almost all parts of the country. According to a report from The Pew Charitable Trusts, this is likely due to favorable economic conditions, robust stock market returns in 2017 and the first half of 2018, as well as short-lived effects of the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act on state tax revenue.

Phil Sletten of the NHFPI notes that NH’s revenue growth from corporate income taxes (comparing the six months ending December 2018 with the six months ending December 2017) is up 34 percent, but that spike is not a standout for the region. Connecticut and Massachusetts had 15 percent and 20 percent corporate income tax revenue growth respectively, while Rhode Island and Vermont saw growth of 98 percent and 131 percent, respectively.

Affording Basic Services

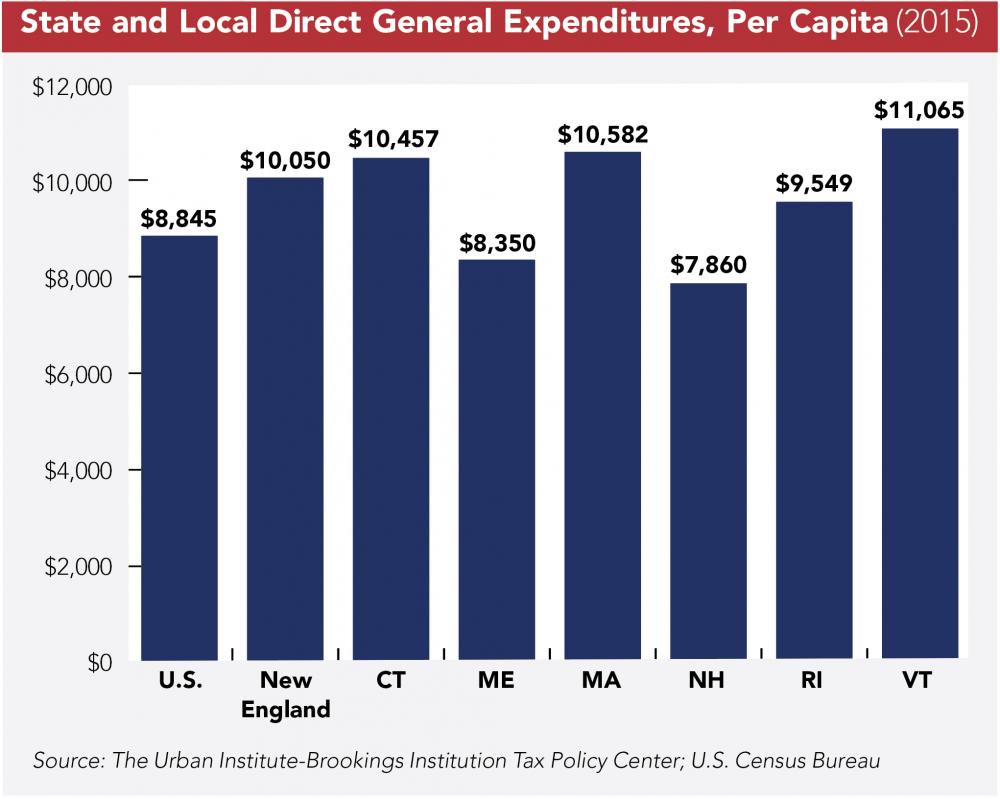

So how does NH afford to pay for basic services? The short answer is that it doesn’t spend as much as other states.

In FY 2015, NH state and local governments combined spent $7,860 per capita—compared to the New England average of $10,050, according to the Tax Policy Center.

In the public welfare category, which includes Medicaid, NH’s per capita direct general spending was the lowest of any of the northeastern states. However, Sletten points out that these statistics reflect NH’s low poverty rate and low number of people eligible for these different public welfare programs.

The argument that NH spends less because it doesn’t have the same demand for services bears truth if you’re well off, says Almy of the mixed-income community of Lebanon. Almy says that during her 23 years of door-to-door campaigning, she encounters a divergence of mindsets on the same street. There are those who adamantly oppose new taxes. And then there are the people who, because of illness or loss of family income, realize there’s no safety net to back them up.

Almy says she has seen the closing or merging of vital social service agencies that could no longer afford to operate. She cites, for one example, the Hannah House, the only agency in the state that offered housing, education and career counseling to unwed mothers. It shut its doors in 2013 after 25 years.

In other categories among New England states, NH is the second-lowest in per capita spending for elementary and secondary education, third-lowest in higher education, lowest in health and hospitals, fourth-lowest in highways, second-lowest in police, and second-lowest in “all other,” according to the Tax Policy Center. A more recent State Higher Education Executive Officers Association study ranks NH the lowest nationwide for higher education funding.

“While nobody wants to pay taxes or to pay more taxes,” says Dadayan of the Urban Institute, “everyone wants to get services. States that are able to provide generous services to their residents are usually highly taxed states.”

While it’s unlikely that NH will ever be a highly taxed state, there will always be some who want to rejigger the way the state collects its money to ease the liability on property taxes. But that means shifting the burden somewhere else. Before that can happen, lawmakers need to kindle the debate without fear of fiery repercussions.

NH Battles the Internet Sales Tax

New Hampshire retailers lure shoppers from neighboring states eager to load up on tax-free refrigerators, TVs, computers and furniture. As long as the purchase occurs in a NH store, their customers drive home without having to pay sales tax.

But the edge that NH retailers have enjoyed for decades is about to change when transactions occur via the internet.

Last summer, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in South Dakota v. Wayfair ruled that retailers selling online have to collect sales taxes for other states where the merchandise is being delivered.

More than not wanting to remit sales taxes, NH retailers don’t know how. Perhaps most vocal in opposition is Gov. Chris Sununu, who in a briefing with the press, said, “If you try to come into our state and force our businesses to collect a sales tax in a manner that violates our laws or the United States Constitution, you will be in for the fight of your life.”

That summer Sununu called for a special session in the legislature to thwart the Supreme Court’s decision. Bipartisan lawmakers crafted a bill that ultimately failed to pass, with critics citing concerns, among other issues, that it was unconstitutional.

But the battle isn’t over. A bipartisan contingent of lawmakers introduced a new bill, SB 242, that passed the NH Senate in February and is under review in the Ways and Means Committee of the House. In Washington, U.S. Senators Jeanne Shaheen and Maggie Hassan, both Democrats, are backing the Stop Taxing Our Potential (STOP) Act as a means to overturn the Wayfair decision.

“In the Granite State,” says Hassan in a press release, “our economy is structured around not having a sales or income tax, and I’ll keep doing everything I can to protect our competitive advantage and the small businesses that drive our economy.”

The NH Retail Association, which opposes a state sales tax, is not formalizing a position on federal legislation, but says on its website, “Continuing that environment is of paramount importance to independent retailers who benefit from the cross-border business.”

Current Issue - April 2024

Current Issue - April 2024