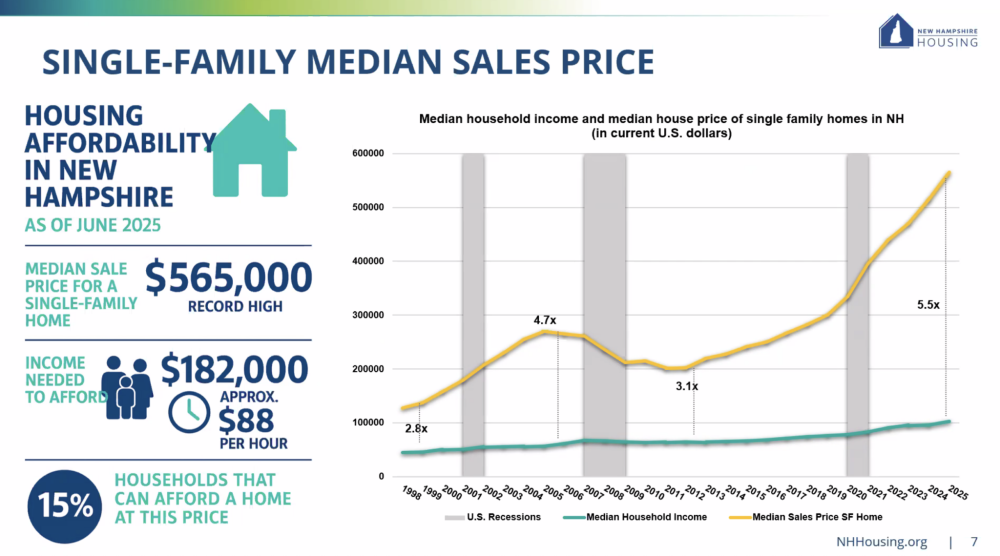

The gap between the median income and the median home price in New Hampshire continues to grow, according to a New Hampshire Housing analysis. (Courtesy of New Hampshire Housing)

New Hampshire’s housing market has an income gap problem.

The median household income has doubled since 1998, hovering at just under $100,000 today. But home prices have jumped at a much faster rate.

Back in 1998, the median New Hampshire home was 2.8 times more expensive than the median income could afford, according to an analysis by New Hampshire Housing, a state-supported housing organization. Today, that same median home is 5.5 times more expensive.

The result is a yawning gap in affordability that appears to only be increasing. It’s a divide that dominated a discussion on the future of housing hosted by the New Hampshire Business Review Thursday.

“The gap between what households earn and what homes cost in New Hampshire has never been wider,” said Heather McCann, managing director of engagement, policy, and communications at New Hampshire Housing.

Economists generally advise households to spend no more than 30% of their gross income on housing. But the prices in New Hampshire make that advice difficult for all but a few in the state to follow.

For instance, in order to afford New Hampshire’s median house price by paying no more than 5% in a down payment and no more than 30% of income a year on a mortgage, a New Hampshire family would need to make $182,000 a year, McCann said. For one person with a full-time job, that averages out to about $88 an hour.

But in reality, the median household in New Hampshire makes $95,628, not $182,000. That means only about 15% of New Hampshire residents could comfortably afford that median home price, according to New Hampshire Housing.

And while the incomes have steadily risen in the last two decades, they have hardly kept pace with housing costs.

Analysts in New Hampshire have struggled to paint a clear picture about where the New Hampshire housing market is going this year. But one underlying factor has stubbornly persisted: low supply.

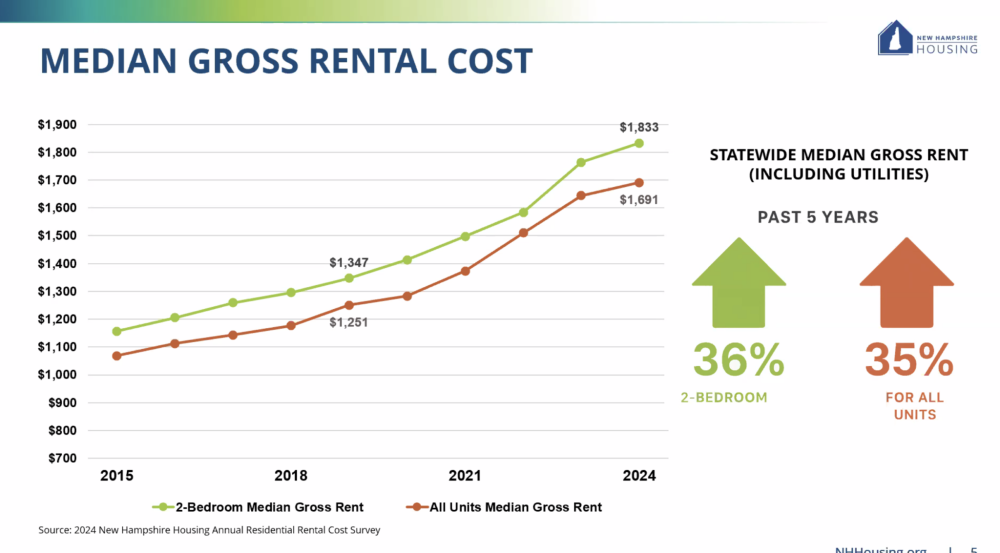

Rents in New Hampshire have increased 35% in the past five years. (Courtesy | New Hampshire Housing)

Rents are continuing to rise after climbing about 35% in the last five years, McCann noted. And because home prices are still high, many individuals and families are staying in rental units, unable to leave, even while the rents rise, she said.

The climbing prices has become a vicious circle for young people in the state, forcing some to leave, McCann said. But retirees are facing increasingly difficult conditions, too. With Social Security paying an average of $2,000 per month, many older residents are paying for too high a portion of that toward their housing.

Rents tend to crowd out other priorities such as food, transportation, and health care, she said.

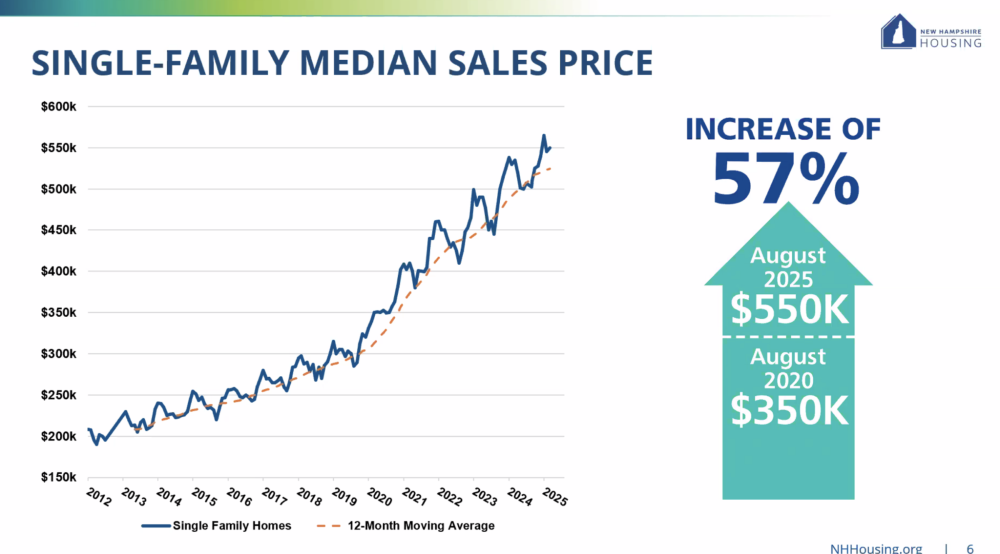

New Hampshire’s post-pandemic boom may have slowed, but it has not stopped. In August, the median sales price hit $550,000 in the state. That was a massive increase from just years earlier; the median price was just over $300,000 in 2019. But that increase was not followed by a similar increase in income for Granite Staters.

The price increases have been slowing: While year-to-year growth in the year following the COVID-19 pandemic saw home prices climbing by around 20% a year, this year, they are higher than last year by only about 2%, McCann said. But the current price levels are still far above what most Granite Staters can afford.

One key metric to assess the housing market is the average time homes stay on the market before they are sold. A short time period indicates a continued buying frenzy, which means prices are liable to rise or stay high.

At the current rate, the total number of New Hampshire’s listed homes could be sold in 2½ months. That is nowhere near the six-month timeframe that housing economists say would indicate a healthy market.

Meanwhile, the houses that are selling more slowly are more likely to be newly constructed. It would take 4.4 months to sell New Hampshire’s inventory of new homes, compared to 1.9 months to sell its inventory of existing homes. That suggests the new homes are more likely to be expensive, McCann said.

The sales prices bear that out: The median price of a newly constructed home is $750,000. That price has jumped 75% compared to new home prices in 2020, driven by a combination of supply constraints, inflation, and tariffs.

New Hampshire single family home prices have increased precipitously since 2019. (Courtesy of New Hampshire Housing)

The bottom line, analysts say: While housing supply may be increasing somewhat, it is not doing so quickly enough. And the housing that is being constructed is still out of reach for many buyers. Until the market cools further and prices fall, that dynamic will continue.

“Even as new homes are added to the market, they tend to be larger homes at a higher price point, and they’re just not easing the affordability pressures for the average New Hampshire household,” McCann said.

That dynamic applies to rental housing, too; while affordable housing projects are being built, many new units are luxury units. More supply — even via more expensive housing — can eventually help lower prices overall, but it is slow. In the meantime, those at the lowest end of the income spectrum continue to suffer the most, she said.

“It’s not bringing up enough units for folks to be able to afford. Prices are still going up,” she said.

Efforts toward affordability

This year, Gov. Kelly Ayotte signed a slew of bills meant to reduce regulatory hurdles to building housing at the state and local level.

One, House Bill 577, would expand the rights of homeowners to build accessory dwelling units on their properties and allow for “detached” units. Another, Senate Bill 284, would prevent cities and towns from imposing requirements of more than one parking space per unit for new developments. House Bill 631 requires cities and towns to allow developers to build housing in upper floors of buildings in commercial zones, with some exceptions. And another, Senate Bill 153, would require state agencies such as the Department of Environmental Services to turn around applications for permits for new housing developments within 60 days.

“This is quite a few very important laws that are definitely going to make a difference, and I’m very much looking forward to seeing how they’re implemented,” Ayotte said at a ceremonial signing ceremony in August.

Any new construction assisted by the new laws will take time. A more immediate fix for struggling home buyers or renters are vouchers that are targeted to lower incomes, McCann and others say. But those vouchers cover only so many people, and go only so far. If prices increase, their usefulness is diminished.

For developers of affordable housing, the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program has proved helpful, said Greg Chakmakas, a shareholder at the law firm Sheehan Phinney, which is involved in housing development deals.

That program allows developers of affordable housing to receive federal tax credits to offset upfront construction costs. Developers will sell the credits to investors in exchange for early funding to allow the housing construction to move ahead. In order to qualify for the tax credits, the developers must include and agree to covenants that keep the rent at an affordable level for at least 30 years.

This year, state lawmakers passed legislation to give developers who receive those federal tax credits additional local state tax relief. Senate Bill 173 mandates that — for local property tax purposes — those properties be assessed at a value of 10% of the annual rental income for 10 years. That law will help lower the annual costs for developers of low-income housing, allowing them to set the rents lower, Chakmakas said.

The effects of the new legal changes will take time to show. But just as the dynamic of insufficient housing supply has persisted, the unwillingness of some communities to embrace more housing has also continued, analysts note.

“There’s a lot of communities who should be commended for being welcoming to affordable housing, and they’re making a lot of strides on that front,” Chakmakas said. “And then there are other communities who want to put up a moat around their town and see nothing changed. And I think a lot of that is kind of based in fear and misconception.”

Those towns that have allowed affordable housing to be built have been happy in the end, Chakmakas argued.

McCann said New Hampshire Housing is aware of continuing resistance and has an advocacy team that seeks to convince local leaders and residents that housing could be a boon for their town.

“Affordable homes just aren’t about individual households,” she said. “They’re about the health of an entire community and state. So when people can find housing that they can afford, local businesses can attract and keep workers, schools and services remain strong, older residents can stay in the communities that they helped build.”

This story is republished fom New Hampshire Bulletin under under a Creative Commons license. For the original story and other NH Bulletin stories, click here.