Downtown Littleton. Courtesy of the Town of Littleton/PurpleFinch Photo Drone LLC.

As demographic shifts and economic prosperity bring change to the NH landscape, cities and towns look to balance growth with maintaining the character of the community and meeting the needs of residents.

Many communities have a master plan that spells out the direction for growth, but a new urbanism, including a desire for walkable communities, is sometimes at odds with decades of automobile-centered living. Malls with massive parking lots are losing out to online shopping and local boutiques and zoning that segregates homes from retail and retail from industry hampers efforts to re-use mills and other large structures.

To meet the needs of the community not only today but into the future, regional planning boards and economic development professionals recommend that a city or town establish a plan focused on its best assets and how they fit into the larger vision for the community.

Robin LeBlanc, executive director at PlanNH, says those who do the best planning are the ones who see the community as a system. “For instance, you can’t make a decision on closing a school without recognizing that it is part of a larger system,” she says. Even if the economics make sense, what happens to the building? Will the town be able to sell it or have to maintain it? What community activities, such as voting or clubs or recreation, take place there?

“PlanNH is about raising awareness about the built environment, that design can affect community,” LeBlanc says. The Portsmouth-based nonprofit shares stories and ideas through newsletters and community charrettes where “we take our collective knowledge and apply it to a specific situation,” she says. “When we do a charrette, the community will ask, ‘What do we do with this building?’ But we say, ‘Let’s look at the big picture.’” Through these charrettes, community members take part in discussions with volunteer planning, design and building experts.

LeBlanc says every decision government makes affects all the parts of the system: infrastructure and buildings, the economy, environmental health and well-being, green space, air, and water. “Too often decisions are based on economy, how much it costs ... towns do not distinguish between spending and investment. Again, looking at the bigger picture is key,” she says.

The focus on economics and taxes sometimes results in locating buildings in areas that don’t serve the people who use them. “Senior housing is often built out on the edge of town, and residents can become isolated. Similarly, closing a neighborhood school and replacing it on the edge of town means no one can walk to school,” Leblanc says.

Some of the communities suffering the greatest economic challenges in NH are the towns that had one large employer, often a manufacturer, that left a really big hole when it closed. LeBlanc says communities shouldn’t chase the dream of an Amazon warehouse.

“One big employer is old school. Start with what you have in place, assets to leverage. What about helping current businesses to expand?” she asks. Communities need to take stock of what benefits they offer businesses and residents that entice them to move there or stay there. “Is it good schools, a variety of places to live, walkability? Do you have things in place that people want?” she asks.

LeBlanc says the most critical asset is social capital; a committed group of people in the community who want to come together and create the desired change.

Claremont Finds the Right Mix

Nancy Merrill, director of planning and economic development for the city of Claremont, says small but important changes are helping the city find the right mix. “I think we are where we want to be,” Merrill says. “Claremont had a lot of issues; we lost a lot of employment in the ’80s and ’90s. For the past 10 years we have been looking at how we reuse old buildings and a host of other issues.

“We have housing that is quite affordable, but also housing that is old, a lot of rental units in older buildings. A survey showed that people want newer homes and apartments,” Merrill says. “The vacancy rate in Sullivan County is very low, and the rents in certain markets are pricing workers out of the quality buildings.”

But the community does support expanding. She says while completing a master plan, residents were asked how big Claremont should be. The city has a population of 13,000 now, and people support growing to 20,000.

“This is a community that would like to see new people move here, as well as grow the industries,” she says. “We had a city center project and rezoned the entire downtown as mixed use. The sawtooth mill became the Claremont maker space. A number of buildings have gone through significant renovation.”

Merrill says the city is particularly grateful to The Common Man Inn and Restaurant and Red River, two businesses that chose the city as a place to expand and helped spark interest in related commerce.

Renovation of a textile mill, above, into The Common Man Inn and Red River helped spark interest in Claremont. Courtesy of The Common Man Inn.

The land-use boards are also supportive, she says. “The planning board and city council made the changes to zoning unanimously.” Claremont has more than 50 percent of the population living in the city center. Historically it was built for multiple use, but you must have the right zoning to get anything done.”

There is a project to convert an old building into housing, adding 36 new units in the downtown. The city has seen growth in industrial areas and had some success in filling some vacant big-box stores with new retail, including a Hobby Lobby and a Harbor Freight store and the Claremont MakerSpace is quickly becoming a hub for development,

says Merrill.

“[The MakerSpace] bought the building from the city. It had a dirt floor. They rehabbed it and opened last year with 10,000 square feet, and [installed] donated equipment from local companies like Hypertherm, Wayland, and Crown Point Cabinetry. There are sewing machines, laser cutters and 3D printers,” Merrill says. “There are classes, memberships to use shared tools, and some people are leasing small spaces within for their own startups. This could be a nice engine for the city and a great place to go and have fun.”

Makers working in the woodshop at the Claremont Makerspace. Courtesy photo.

Merrill says the historic downtown should operate with a broad mix of business and housing. “We had to do quite a few changes to the zoning. If a light industry doesn’t have noxious fumes, then it’s okay to be here. We can have residents and restaurants in the same building.”

The next big project is “rethinking” Pleasant Street, a two-block area in the central business district prime for redevelopment using incentives such as 79E, a community revitalization incentive, and ERZ, or Economic Revitalization Zone, to encourage developers to build in economically depressed areas. Specifically, 79E lets developers essentially freeze the property tax value for a few years after improvements are made.

“We think it is a good tool,” Merrill says. “Most of the downtown buildings are old and costly to bring up to code. If you like them and don’t want them knocked down, it’s a great investment to help developers reach a return.”

Reimagining Derry

In Derry, a town that has a higher population than some NH cities at about 34,000, officials are offering economic incentives, seeking community input and focusing on things that make the town special, including a central location, an established music culture, and its historic downtown.

Economic Development Director Beverly Donovan says the town just finished an application round for a matching grant program where businesses can receive up to $5,000 in a 50/50 match for façade improvements. The funding comes from the town’s revolving loan fund with the Regional Economic Development Center and is not raised through taxes. It is a common and effective way for communities to inspire businesses to spruce up.

The first round ran from January to June of 2018 and was focused on West and East Broadway, where there are several creative economy businesses, restaurants, and consignment shops. Donovan says the town expanded the program in July 2018 and added Crystal Avenue and Birch Street, and have already received about a dozen applications.

Top: Sun Bistro on West Broadway in Derry. Bottom: The restaurant’s proposed facade. Courtesy of the town of Derry.

Derry is also using tax incentives to spur development. The most recent example is a project undertaken by the Anagnost Companies using the 79E tax incentive to redevelop a former warehouse on Crystal Avenue into a bank, a physical therapy office and other small retail.

Donovan says the city has invested time getting feedback from the community. Staff even went back through revitalization reports, dating to about 1989, and created a spreadsheet of all the general improvements requested to see what had been accomplished and what was left to do. “At a meeting [in February 2019] we had a packed room and a lot of representation from many corners; people new to town and long-time residents. The biggest takeaway was that people seem very open-minded and like what they have been seeing in the past 10 years,” she says.

One eye-opening observation, says Donovan, was the lack of ADA parking in the downtown, making it difficult for patrons to visit the opera house and other venues. “So, we have to look at that,.Meanwhile, all of this feedback will go into the master plan for the community,” she says.

Donovan says Derry is ideally situated, “in a really great spot right off of 93 with access to north and south, to Boston and Manchester. There has been a lot of attention in Salem and Londonderry—we’re in the middle and have what others are trying to create,” Donovan says. “Derry has an organic downtown with nooks and crannies and lots of little places ... downtown really is a great part of Derry.”

Littleton’s Cultural Focus

Littleton’s Cultural Focus

Considered NH’s most welcoming attraction, a bronze sculpture of literary character Pollyanna (in tribute to hometown author Eleanor H. Porter), the little girl known as the eternal optimist, offers a welcome wave and is considered the ambassador of cheer and community spirit. And Town Manager Andrew Dorsett says community spirit is the town’s formula for success. “Littleton has for some time had a continuity of people, entrepreneurs, thinking long range and supporting each other.”

Dorsett says a recent example was when several small businesses rallied support for zoning changes to help a local brewery get the variances it needed. Cheering the town’s accomplishments has also helped, garnering visits from members of the state legislature, the governor and congressional delegation, who all helped the town secure important development funds in the past few years. “When we needed support, they were there for us. It is an old mill town that could have died.”

He says the master plan calls for preserving cultural assets, not just buildings. “We created a cultural arts commission to find out what is going on in town, what do we have, like Pollyanna, and what do we want. We were recently awarded a $200,000 grant (from the NH Land and Water Conservation Fund program) for a park in the river district to create an exercise area, hold concerts and farmers markets.”

Cultural arts professionals in Littleton engaged in community planning. Courtesy of the town of Littleton.

Such amenities attract new residents, but finding a place to live can be challenging. Dorsett says Littleton has a tight housing market and needs market-rate multifamily units and homes in the $250,000 to $300,000 range. Despite the limited supply, many younger people are moving in. Formerly vacant second floors are now being renovated and rented to young people, professionals, engineers and nurse practitioners, who previously may have wanted a starter home. Now parking is an issue, but Dorsett says that is a good problem to have.

“The automobile revolutionized America, but the generation coming in wants to get home, relax and walk downtown for a few brews, or to see a movie, or get a haircut,” he says. “They want the amenities of a city, but in an independent funky setting.”

Dorsett says the appeal of Littleton goes beyond NH. “A man from Arkansas, who came for a visit at the worst time of the year, told me he wanted to know if he could stand the winter; he is already getting ready to move here,” he says.

“I met a young man from Tennessee who came here without a job and ended up opening a business on Main Street.

He said we have it all—the downtown, the mountains and the trails. People who live here take it for granted. A man from Houston said the beach, the mountains and Montreal are all within a couple of hours. Back home he could spend that time just driving across the city. “

Dover Guided by Master Plan

Dover has grown significantly over the past few years becoming the fourth-largest community in NH. That development, which included a parking garage, both workforce housing and high-end rentals, and infill, has been carefully guided by the city’s master plan, says Assistant City Manager Chris Parker.

“We are very fortunate to have great volunteers to work on it, as well as community engagement and thoughtful policy makers, including the City Council—people who take time to understand what it says and what we want as a city,” Parker says.

As Dover approaches its 400th anniversary in 2023, Parker is asking, “What do we want to be when we grow up? We want a real sense of a working downtown, not touristy, not quaint … it needs to be live, work and play. The city also wants to have variety of housing choices, such as the mills, starter homes and options “in the middle of nowhere,” he says.

“I think we’ve done a great job of promoting multiple styles of industrial use too … we have the largest Liberty Mutual site outside of Boston, and we have lots of mom-and-pop retail downtown.”

Parker says Dover reviews land use regulations regularly. “Most communities do a large project every five to 10 years to cover the central chapters; we do one a year on a constant basis so it is a dynamic and strategic document. It’s the same amount of money each year as opposed to a big amount every 10 years. It is also easier to engage with the community.”

Every January, the planning board evaluates land use regulations and recommends changes. “I’ve been here 21 years, and in 2002 we had 48 zoning amendments all at once. It is cumbersome and scary to do so much at one time. Five to 10 a year is much more communicable, and you can break down the changes. It also allows iterative changes as opposed to sweeping changes. If we tweak this here and adjust this there, we think very strategically,” says Parker.

Twice a year, Dover city staff meet with developers, surveyors and engineers to talk process. “The development community suggests things, and we recognize they can be fully self-serving. If so, those don’t go anywhere. Other times they have a good point,” Parker says. “Without regulators and developers working together, you won’t have a city that is dynamic and vibrant—just a bunch of regulations that sit on the shelf and don’t do anything.”

He says it is good to be aware of what other communities are doing, but not to try to replicate it and risk losing what gives a community its unique identity. “I’d rather focus on what makes Dover special,” Parker says.

Tap In to Expertise

New Hampshire’s Regional Planning Commissions (RPCs) provide technical assistance to communities on a range of topics including land use, environment, economic development, infrastructure, and emergency preparedness, says Tim Murphy, executive director of the Southwest Region Planning Commission. “We also offer processes to assist municipalities in determining a desired future, such as facilitated discussions among community members, surveys and group exercises to identify and establish priorities, community vision, goals, objectives, strategies, etc.

“Many of New Hampshire’s RPCs are currently active in projects that examine the relationship between changing demographics and community needs. For example, understanding the linkages between workforce needs and housing, nightlife, broadband,” Murphy says. “To address an ever-increasing aging population, along with a corresponding decline in youth and younger working-age population, what should communities be doing to be better prepared for this future?”

Murphy says planning assistance can include evaluating economic opportunities, housing, transportation options, and opportunities for social engagement. RPCs, meanwhile, can help communities access grant funding. Redeveloping an eyesore can be a catalyst to spur further growth.

Planning for the Ages

While community planning focuses heavily on the types of businesses and housing needed, just as important is creating a community that is welcoming to all ages. AARP State Director Todd Fahey says there are two main spheres in communities: the built environment, including housing and transportation; and the social environment, such as recreation and civic engagement.

Currently NH, which has one of the oldest populations in the country, has about 15 communities taking part in the AARP Age-Friendly Communities program, including Dover, Goffstown, Londonderry, Portsmouth, and collectively about a dozen towns in the Mt. Washington Valley. By contrast, Maine, the oldest state in the nation, has more than 60 communities participating.

Goffstown improvements include new business facades, benches along Main Street, and landscaping. Courtesy photo.

Fahey says it is a volunteer-driven program whereby communities become more intentional in eight domains of livability that include:

• Outdoor Spaces and Buildings

• Transportation

• Housing

• Social Participation

• Respect and Social Inclusion

• Civic Participation and Employment

• Communication and Information

• Community and Health Services

Fahey says many components in the social sphere are less costly to address and, in many ways, just as important as others. Communicating to all residents the ways to become engaged is crucial. “Whether people are aging in place and downsizing to an apartment, or are newcomers to your community, they need to know what is available,” Fahey says.

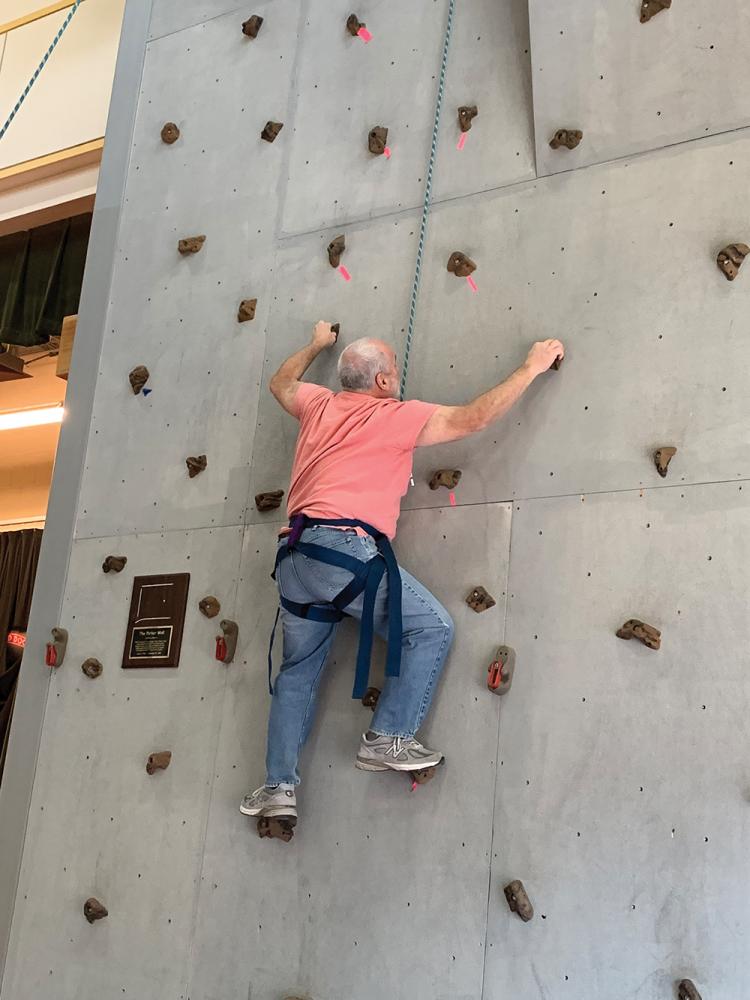

A participant in Portsmouth’s indoor rock wall climbing program. Courtesy photo.

A participant in Portsmouth’s indoor rock wall climbing program. Courtesy photo.

The Age-Friendly program helps communities recruit volunteers and evaluate the community’s assets, needs and challenges. “Sometimes improvements are really small, something no one thought of. Does your community trail have benches so that someone can take a little rest along the way? Does your ballfield have any shaded seating so the grandparents can come watch the game, too?”

Civic engagement and employment opportunities are also important, not only for the individual, but for the value they bring to the community, he says. Fahey says as a community embarks on the process, it is important to remember: “The program is really a roadmap and not a prescription. There is no requirement to make any changes ... [but] it is a valuable tool for what a community can do to keep residents of all ages active and engaged.”

Current Issue - April 2024

Current Issue - April 2024