This story is being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.

This story is being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.

Although it feels like we’re going through an unprecedented emergency right now, Concord, like much of the rest of the world, went through something very similar a century ago with the disease that came to be called the Spanish Flu.

“You see how quickly the hospitals in Concord were overwhelmed. The Elks Club building on Main Street was turned into an emergency hospital and staffed with visiting nurses and volunteers,” says Byron Champlin, who has studied how the 1918-1919 global pandemic affected Concord.

“City officials in Concord in late September of 1918 closed down pretty much any place that people congregated – theaters, barbershops, soda shops, saloons. Churches discontinued Sunday services, they closed the schools down. … Fraternal organizations, book clubs, most announced that they were suspending gatherings. Eventually, the Board of Health directed only immediate family to attend funerals.”

Sound familiar? So does this: Until it couldn’t be ignored officials underplayed the severity, Champlin said.

“There were little items in the paper back then, often placed without attribution. They would say things like ‘This is just the grippe, just the common grippe’,” he said, using an old term for a cold or flu. “It’s notable that the Hopkinton Fair went on as usual in September, with about 3,700 people gathered there.”

The disease arose in the U.S. in the fall of 1918, as the nation was fighting hard in World War I. Officials clamped down on references to the epidemic, fearing it would undermine efforts in the war, which ended in November 1918. Only after the war ended did news become more widespread.

As an example, Champlin pointed to banks.

“They were extending hours so people could come in and buy war bonds,” he said. “Part of the feeling that you didn’t want to anything to put a damper on war morale.”

“It wasn’t until the disease peaked in Concord that you saw real action,” he added.

Amateur historian

Champlin, of Concord, says he has “always been an amateur historian” and after retiring from the insurance industry and philanthropic work, wanted to write a history of Concord in World War I. That’s when he realized the severity of the Spanish Flu.

“There are 43 names of the war dead on the monument in Memorial Field. Five died of illness, 3 of them of influenza,” he said. “Even on (the battlefront) it reached out.”

Worldwide, it’s estimated that the Spanish Flu, a variant of the H1N1 virus that caused a smaller pandemic in 2009, killed somewhere between 20 million and 100 million people – at least 1% and perhaps as much as 4% of the entire global population at the time. The death estimate in the United States was said to be 675,000, although that’s highly uncertain.

Nobody knows how many people died in Concord, Champlin said.

It’s not entirely clear where the 1918 pandemic originated but it spread when people contacted one another.

A major point of transmission through New Hampshire was Fort Devens military base in Massachusetts, a major wartime operation where thousands of soldiers and other people came and went even as the disease grew in severity and reach.

The disease is called Spanish Flu because Spain was the only country in Europe lacking controls on newspapers during the war. Press freedom meant that as the disease was growing, Spain was the only place that saw reporting about it.

Not much reporting

Reporting on the pandemic was almost nonexistent in the United State during the war because of press restrictions, which helps explain why this national disaster has been somewhat forgotten.

“There are no photos that I’ve been able to find of anything happening in Concord during the pandemic,” said Champlin. Newspaper reports of the time are sketchy until after it became a full-blown epidemic, and histories of the time often depict the disease mostly as a short-term irritant.

The Granite Monthly, a magazine devoted to “literature, history and state progress” of New Hampshire, has no articles about the disease in the bound edition of its 1918 publications. “Influenza” is mentioned only occasionally, such as to explain why the Congregational Church didn’t hold its centennial celebration on time or why a Food Administration Booth urging people to conserve food in wartime sometimes drew small crowds. “The full effectiveness of the booth was interfered with …. by the influenza epidemic,” the magazine noted, before discussing the use of “lantern slides” in movie theaters to get the food-conservation message.

“You know how combat veterans don’t like to talk about their experiences? I think anybody who survived influenza didn’t really want to talk about it. The thinking was, we need to move on,” Champlin said.

Champlin wrote a lengthy piece published in the Monitor in September 2018, the centennial anniversary of the disease really striking home. He compiled all the stories of deaths that he could find.

“It was repeated many times in the news columns of the Monitor of family members passing away within days of each other. There were several double funerals. It’s heartbreaking.”

That kind of sorrow, worsened by ignoring the problem until it was too late, which is why Champlin thinks it’s important to remember the last time the world reeled because of a virus.

“From my perspective, it’s important for people to understand how severe this kind of thing can be,” he said. “We should learn from our mistakes.”

(David Brooks can be reached at 369-3313 or dbrooks@cmonitor.com or on Twitter @GraniteGeek.)

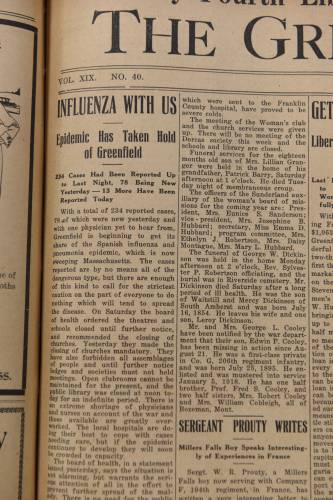

Frontpage of the Greenfield Recorder October 2, 1918 with references to the Spanish Flu. Staff Photo/Paul Franz

These stories are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.)

Current Issue - April 2024

Current Issue - April 2024