As an African American nurse, health care provider, and public health worker, Bobbie Bagley says she has “lived it” from both sides. The “it” being the inequities and systemic racism that exist in the health care system—inequities that have come under the spotlight of the pandemic as COVID-19 disproportionately affects people of color.

As an African American nurse, health care provider, and public health worker, Bobbie Bagley says she has “lived it” from both sides. The “it” being the inequities and systemic racism that exist in the health care system—inequities that have come under the spotlight of the pandemic as COVID-19 disproportionately affects people of color.

Inequities existed long before COVID-19 though, says Bagley, director of the Division of Public Health and Community Services for the city of Nashua. She recalls her mother’s experience in an emergency room after falling and suffering a pelvic fracture. “I was astonished at how she was treated. The nurse slammed the bed up; she was there for an injury. As a nurse myself, I thought maybe she’s tired or doesn’t like old people,” says Bagley. “This is what we do, we try to make excuses. The last place you try to go is it’s because I’m Black or Brown.”

Bagley says it was hard for her to defend her profession as she could hear the same nurse in the next room treating another patient nicely. “The disparities are real. Racism as a public health issue is real. That is really hard for our community, our society and our country to grapple with.”

Dr. Marie-Elizabeth Ramas, president-elect of the NH Academy of Family Physicians, says there are many documented examples of inequity and bias in the health care field. One study revealed Black and Latino patients often are started on blood pressure treatment later than white patients, she says, while a 2016 study involving more than 200 white medical students and residents showed half thought Black people didn’t feel pain the same way as those who are white. “These concepts of practice and our unintended assumptions infiltrate our daily interactions,” Ramas says.

Going through training in the 1990s as a female physician, Dr. Joann Buonomano, chief medical officer of Greater Seacoast Community Health, which operates health centers in Portsmouth, Rochester and Somersworth, says she has many examples of subtle and traumatic microaggressions toward patients and colleagues based on race and gender. But, she says, she has also seen colleagues learn to reach out to others of a different gender or sexual orientation or race and connect in a way that people appreciate.

What the pandemic has underscored is the importance of addressing these inequities. “You really saw the inequity unfold very clearly,” says Bagley. “I had seen the same disparity in every other health issue we’ve been dealing with. We’ve seen it with HIV and AIDS; we’ve seen it with maternal and child health.”

COVID Inequities

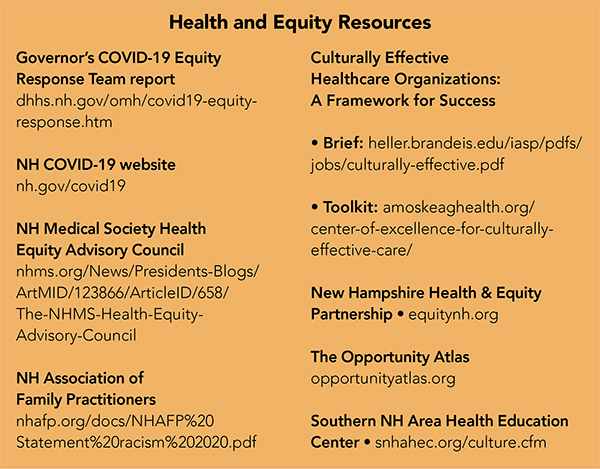

As it came to light nationally and in NH that COVID-19 was disproportionately affecting people of color, Gov. Chris Sununu established the Governor’s COVID-19 Equity Response Team in late May, charging the team with developing a strategy to address those inequities and oversee the implementation of the recommended plan.

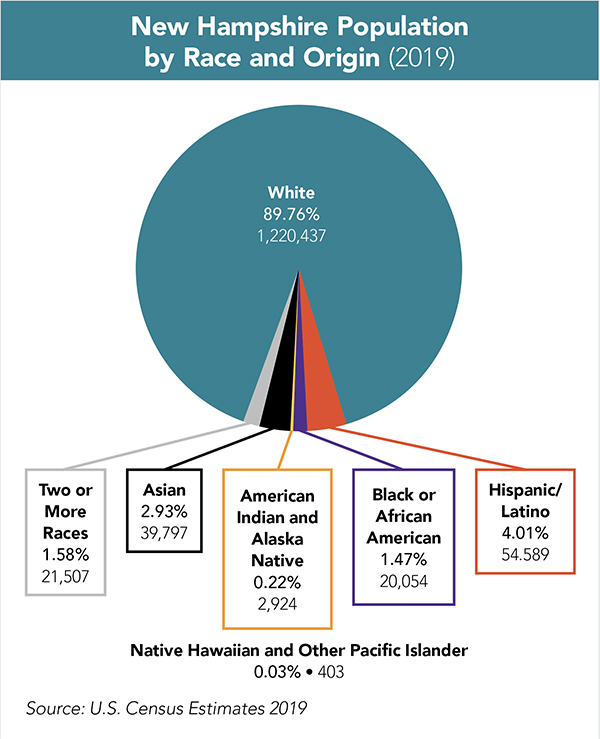

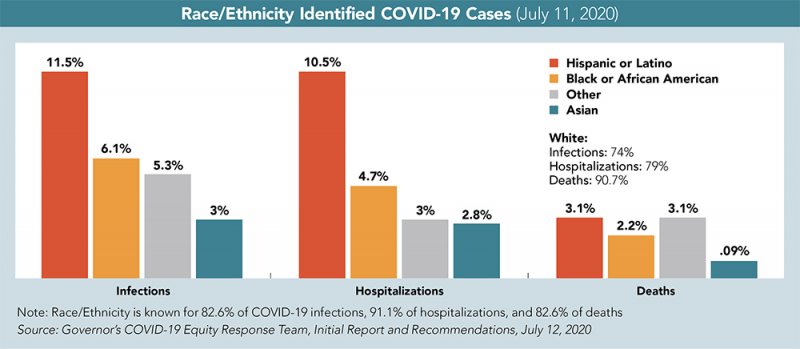

State data released on April 2 revealed while Hispanic/Latinos comprise only 3.9% of the population, they comprised 6.1% of COVID-19 cases; and while Black or African Americans comprise 1.4% of the population, they comprised 5.4% of the state’s COVID cases. By July 11, that disparity had grown to Hispanic/Latinos comprising 11.5% of cases and Black or African Americans comprising 6.1% of the state’s cases.

State data released on April 2 revealed while Hispanic/Latinos comprise only 3.9% of the population, they comprised 6.1% of COVID-19 cases; and while Black or African Americans comprise 1.4% of the population, they comprised 5.4% of the state’s COVID cases. By July 11, that disparity had grown to Hispanic/Latinos comprising 11.5% of cases and Black or African Americans comprising 6.1% of the state’s cases.

“Clearly we are seeing a racial disparity with black New Hampshire citizens dying of COVID at a rate three times higher than white citizens, and Latinos at a rate twice as high,” says Buonomano, citing the NH COVID-19 Interactive Equity Dashboard and noting that the rates may be even higher as race and ethnicity is only recorded on 80% of death certificates.

While infection rates aren’t necessarily related to a health care provider’s racial bias, subsequent treatment can be. “I really think it’s a matter of individual response, of taking responsibility to recognize your own biases, which is something every professional needs to do. We are called upon through the Hippocratic oath to be aware of our own biases. As health care leaders we can help our organizations recognize the bias that exists and try to change it,” Buonomano says.

Ramas says while the pandemic tested the limits of the country’s medical infrastructure, it also highlighted, “the very stark differences that were occurring between communities of color and the majority population. [It] was something that could not be denied any longer because the toll was so provocative.”

Kirsten Durzy, an evaluator at the NH Department of Health and Human Services who serves as the equity subject matter expert for the COVID Response Team, says, “What is different in COVID-19 is that the scale of it is unrelenting. It is like a tsunami rolling in and picking up every disparity that existed and bringing more damage with it. For anyone in a vulnerable position, the damage is amplified.”

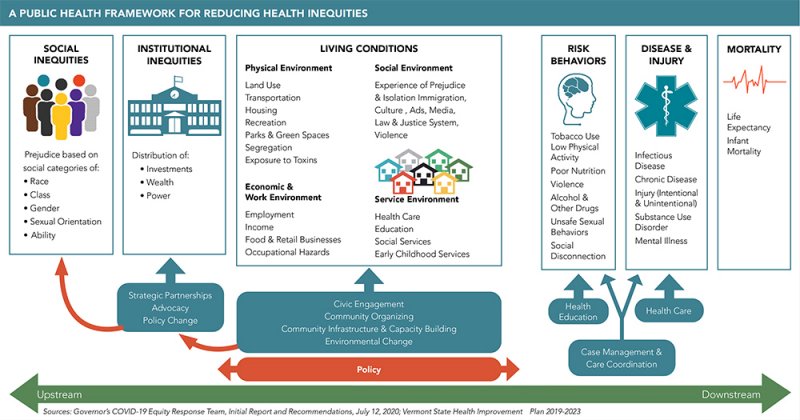

The COVID-19 Equity Response Team issued recommendations in July 2020 intended to create a more equitable heath care system. They also explained how social determinants lead to health care inequities. The report points out while race is a social construct with no actual basis in biology, racism is real, leading to judgments, assumptions, beliefs and attitudes that affect people’s behaviors toward others and the systems society creates, which, in turn, affect individual health.

Dr. Trinidad Tellez, the former director of the Office of Health Equity in the NH Department of Health and Human Services who chaired the COVID-19 Equity Response Team, says, “When you are talking about equity, you really need to center the people who are most affected so efforts are using what we call community engagement strategies and partnering with community members. That way solutions are co-created, and they’re not just dictated by people or organizations with power or resources.”

Working Upstream

Addressing issues of equity in the health care system means tackling issues of equity in society. “Health equity requires the removal of obstacles that prevent it, such as poverty, discrimination and the related consequences of powerlessness, lack of access to jobs, fair pay, quality education, housing, safe environments and health care,” the COVID-19 Equity Response Team report states.

The team recommended reviewing all state COVID-19 guidance for equity in practices, assuring workers, particularly essential workers, are protected, including providing hazard pay, on-site education and testing, adequate supplies of personal protective equipment and other physical safeguards in work settings, as well as guaranteed sick leave policies.

Also among the recommendations are diversifying the public health and social service workforce across all sectors and levels; employ COVID-19 Response Community Health Workers to serve in the affected communities who are suffering disproportionately from COVID-19; and establish and fund community-led, public-private partnerships to identify and implement strategies that address unemployment, job creation, and the fiscal loss and financial insecurity resulting from COVID-19.

Some of the goals, such as testing all high-risk populations; mandating mask use; and providing disparity data dashboards are already being implemented. The report also identifies social determinants of health, which include factors like socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, and social support networks, as well as access to health care. How do those play into the pandemic? An example would be people in low-wage jobs living together to save on the cost of housing and who also work in frontline positions, which increases their overall risk of exposure.

“One of the greatest things we can do to improve the health of a population is to work on social determinants,” says Tellez.

Bagley says its important to understand how social determinants are driven by underlying institutionalized racial discrimination.

The immediate past president of the NH Medical Society, Dr. John Klunk, says he planned to focus on social determinants during his tenure as president but the pandemic took over. “We went through the pandemic, the killing of George Floyd and the amazing spread of the Black Lives Matter protests,” he says. “In starting to look at some of the COVID data on health disparities in Black and Brown communities, I personally wanted to do something.”

Klunk says he approached the board of the Medical Society about making a formal statement and enlisted the aid of Tellez to develop a document that was accepted unanimously by the 30-member governing council. But during the process, he realized it seemed inadequate, and he wanted to turn those sentiments into action.

In August, the Society formed a Health Equity Advisory Council, which includes Ramas. She says the goal of the council is not only to advocate for change during the current crisis but help physicians see the connection between their own life experience, that of their patients and the effect it has on patients.

“There is a lot of education that needs to happen both within and outside of the medical community. Traditionally New Hampshire has been a predominantly white state, but it is becoming more diverse,” Klunk says. “If you look at the literature and the data, health care is not immune; racism is structural, and it is institutional in medicine and across society,” he says.

Models for Change

Betsy Burtis, chief officer for integrated health services at Amoskeag Health in Manchester, says creating a culturally effective health care model means making a commitment to doing it forever. “It is not something you do once and you’re all done. It is not a box you check off of a list. It is constant. You need to examine every existing policy and procedure, and new ones as they are written.”

When providing information to patients it should be culturally-centered with an understanding of how the patient’s background may inform their understanding. “Countries in Africa have a totally different health care system. So, for people coming here, it is not just about learning the language, it is learning the system.”

Amoskeag Health has the “Culturally Effective Healthcare Organizations: A Framework for Success” toolkit available to be downloaded. It is based on a brief that Tellez co-authored in 2015 and focuses on seven elements: leadership, institutional policies and procedures, data collection and analysis, community engagement, language and communication access, staff cultural competence, workforce diversity and inclusion.

The Southern NH Area Health Education Center, which provides workforce development for current and future health professionals with a focus on under-served communities, created a Center for Cultural Effectiveness to champion the framework.

Director Paula Smith says training community health workers (CHWs) who act as a bridge between the community and the health care system is one of the most important parts of the program. “They help people navigate the system and act as a cultural broker. They are a trusted member of the community who understands the community,” she says.

Tellez says because community health workers are embedded, they can be more effective in reaching patients than other providers and they are also context specific. She says a CHW from the North Country will better understand the culture of the North Country, while a CHW in Manchester or Nashua might have a deep understanding of and connections to a community of color or an immigrant population.

Allaying Vaccine Concerns

Several organizations are already reaching out to provide information about COVID-19 and the vaccination process as recent surveys show that among those who do not plan to take the vaccine, the majority are people of color. “You have to look at the historical context of where that comes from. Our system has created reasons for a lack of trust,” says Bagley. “Lack of belief in our health care system, and even some of our public health workers and measures, stem from the systematic racism that existed for so long. We must knock down these institutional barriers.”

Bagley says research has revealed that eugenics was done even in NH, especially among the Native American population. There was sterilization in the South of poor black women. Historically, there were often denials of service, with people getting turned away at emergency rooms.

An Aug. 21, 2020 article on Smithsonian.com, “Racism is a Public Health Crisis,” by Katherine Ott, states, “Infant mortality rates in 1960, 1980, and 2017 were over two times higher for Black infants compared to white infants. In 1980, Black and white women died from breast cancer at the same rate. In 2017, Black women were 40% more likely to die of the disease, despite having the same kind of tumors. People of color have higher sickness and death rates from tuberculosis, diabetes, ulcers, pernicious anemia, high blood pressure, heart disease, asthma, and COVID-19.”

Burtis says expert advice on how to combat the pandemic has evolved during the past year. “I can see where people would have their doubts.” As such, Burtis says case workers and community partners are being equipped with outreach tools and messaging such as posters in prominent locations and cards that can be handed out to patients. She adds the CDC has some easy-to-understand language that translates well, letting people know the vaccine is safe and what they should expect, including the two-shot course and possible side effects.

According to Durzy, DHHS will be doing significant outreach and hosted community vaccine information sessions in January with plans to tape a session and make it available online. She says the sessions are intended to be transparent with community members and grew out of the work the state had been doing with the NH Public Health Association and the COVID-19 Equity Task Force.

“We share the information about the two vaccines available and have a conversation about the information out there that may or may not be truthful or fact-based. We talk about the fear and hesitancy, about the allocation process, what we know and don’t know,” Durzy says. “This is a response unlike any we have ever attempted.”

Changing Attitudes

Changing Attitudes

One of the best things people can do to deter implicit biases and assumptions is put themselves in someone else’s shoes, says Ramas. When so many are trying to make it through the day, it is easy to forget another person’s perspective, she says.

“We hope to magnify that across the state to help our fellow physicians find a breath of energy in the midst of this pandemic—these two pandemics, the COVID crisis and a racism crisis,” Ramas says. “Racism is a cancer that has infiltrated the health and wellness of our communities for centuries in America, and it is time for us to do our part.”

The state’s Office of Health Equity has been instrumental in data collection and analysis, says Klunk, but health systems and individual physician practices don’t have resources or the awareness that it is important to collect this data.

“Once you highlight disparities you can do root-cause analysis long term,” says Klunk. “Our physicians care about their patients and want to do the right things, but they had their heads down trying to get through the day even before the pandemic. Hopefully we can provide some tools, create more awareness; that’s the first step in creating real change.”

This article was produced by Business NH Magazine as a partner of The Granite State News Collaborative for its multiyear project exploring race and equity in NH. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.