KEY POINTS

-

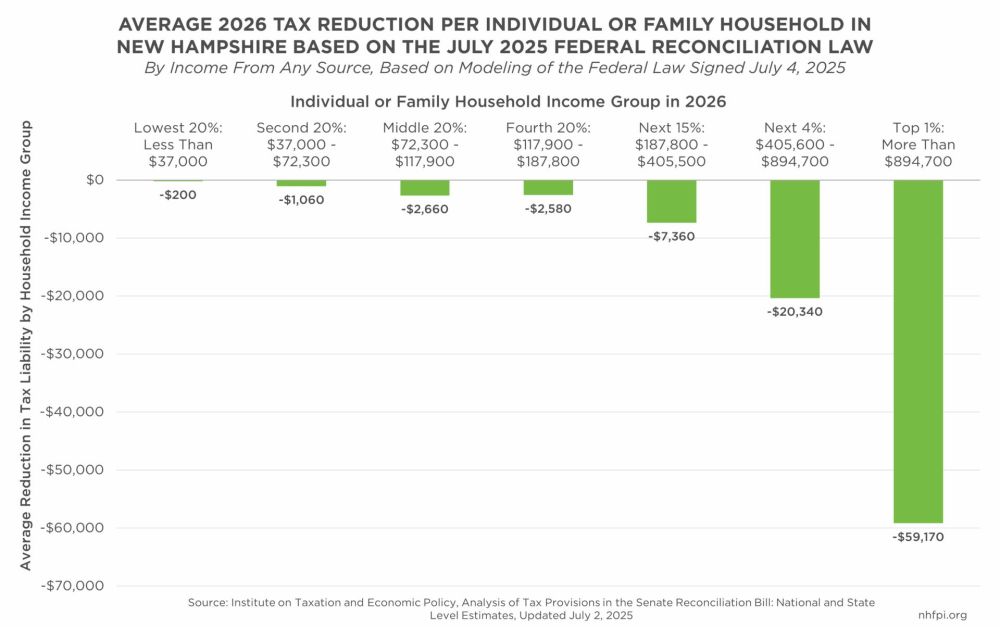

- The federal reconciliation law will extend the 2017 tax reductions permanently, lowering future taxes for all income groups, with two in three dollars benefitting Granite Staters going to the top 20 percent by income

- Several other new tax provisions, including new deductions or credits for tips, overtime pay, automobile loan payments, state and local taxes paid, and older adults, are temporary

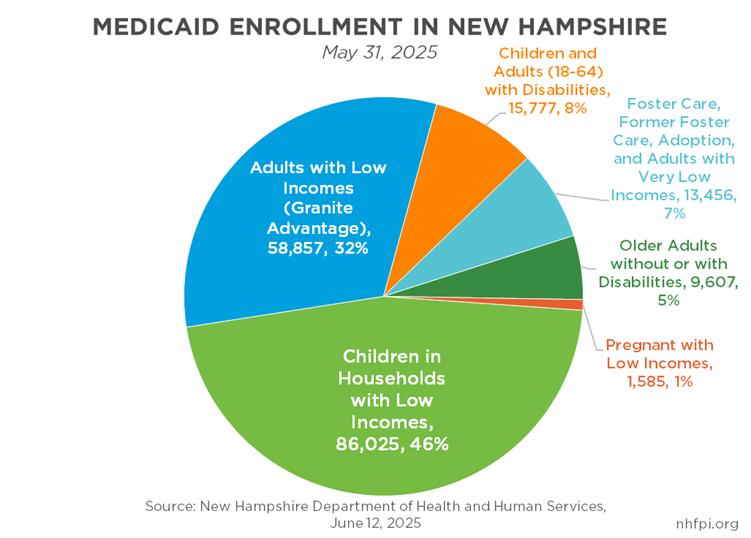

- Federal Medicaid expenditures in New Hampshire may be $2.3 billion lower in the next ten years than they would have been under prior law, due primarily to disenrollments from work and more paperwork requirements for eligible individuals, making many currently-eligible legal immigrants ineligible, and cost shifts to the State

- Work requirements in Medicaid could disenroll 20,000 Granite Staters, while another 4,000 would be newly subject to work requirements for food aid

- Several significant law changes made in 2022 to support clean and renewable energy will expire soon

- New law substantially increases immigration enforcement spending

- In total, projections indicate new law will add more than $3 trillion to federal debt in the next ten years

The new federal reconciliation law, signed on July 4, 2025, makes significant changes to programs that will impact Granite Staters. These changes include direct interactions with individuals and families, including reducing taxes for most residents, particularly those with higher incomes, and limiting access to both health services and food assistance. The new law also impacts the financial outlooks for both the State and federal governments, which may affect subsequent policy choices and services.

This legislation has been commonly referred to as the 2025 reconciliation law, based on the process used to pass it through the U.S. Senate; H.R. 1, or House Resolution 1; the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the name used in the U.S. House’s version of the bill; or its formal name, Public Law Number 119-21.[1] This analysis will refer to this new law as the reconciliation law.

The Big Picture and Total Costs

Although it makes many significant changes, this new reconciliation law is primarily a tax law. The new law makes permanent many of the individual income tax rate reductions from the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that were expiring at the end of this tax year. Some new tax provisions were also implemented, including the temporary elimination of taxes on tip income, overtime pay, and income used to make payments on automobile loans. In contrast, taxes on estate transfers were reduced permanently, and the federal Child Tax Credit was modestly expanded. In total, two out of every three dollars in reduced federal taxes for Granite Staters will benefit the top 20 percent of taxpayers by income in 2026, while filers in the bottom 20 percent of income earners will see an average tax reduction of $200.[2]

The costs of enacting those tax changes, which are projected to increase the federal debt by about $5.36 trillion over the next ten years, will be partially offset by limiting access to services that serve people with low incomes and reducing planned investments in clean and renewable energy technologies.[3] Changes to Medicaid, including work requirements for certain enrollees, more stringent procedures for enrolling and remaining enrolled, and eliminating benefits for certain legal immigrants, are projected to reduce expenditures by about $990 billion over ten years relative to expectations under prior law.[4] Food assistance changes, including to work requirements and requiring states to pay more of those benefits, will also reduce expenditures, as will changes to federal student loans and to energy, manufacturing, and other tax credits.[5]

However, the reconciliation law is still officially projected to increase the federal debt by $3.4 trillion over the next ten years relative to the January 2025 policy baseline established by the U.S. Congressional Budget Office. This net amount accounts for both net reductions in revenue and net reductions in spending, although spending does increase substantially for defense and immigration enforcement under the new law.[6]

Including the approximately $717 billion cost of paying interest on the new debt incurred, the nonprofit Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimated the new law will add more than $4.1 trillion to the national debt through Federal Fiscal Year 2034.[7] Impacts on the economy and economic growth from the new law could change the final total, but differing analyses suggest any positive effects on the economy will be limited at most. While the Tax Foundation estimates that the new law will help economic growth over the next ten years and, conversely, the University of Pennsylvania’s Penn Wharton Budget Model projects that the legislation will hurt economic growth relative to what it would have been, both models estimate more than $3 trillion will be added to the national debt over the next ten years because of this new law.[8]

Analyses suggest this new reconciliation law will, on average, reduce the resources available to households with lower incomes while increasing the financial well-being of households with higher incomes.[9]

Tax Policy Changes and Impacts by Income Group

In December 2017, federal policymakers enacted the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA).[10] The TCJA reduced taxes for most households by lowering rates and making other changes, such as creating a larger standard deduction and Child Tax Credit amounts.[11] However, most of the benefits of the TCJA went to the highest-income households, particularly those with certain types of business income and those that benefit from intergenerational transfers of significant wealth.[12]

The TCJA made several permanent changes to the tax code, such as reducing the top corporate tax rate from 35 percent to a flat 21 percent rate. Many of the individual income tax provisions and certain provisions related to business income, however, were set to expire at the end of 2025. As a result, the U.S. Congress had to act this year if policymakers wanted to avoid permitting these provisions to expire. Unlike the TCJA, which was purely a tax bill, policymakers sought to offset the impacts of reducing taxes by reducing spending in the same piece of legislation.

However, the new reconciliation law took steps beyond extending and making permanent the TCJA individual tax provisions that were expiring. The law made new changes to the tax code, including some temporary changes that will themselves expire after 2028. New changes from the TCJA include:[13]

- A boost to the Child Tax Credit maximum from $2,000 to $2,200, but not an expansion to a fully refundable version as was implemented in 2021[14]

- An increase of the Estate Tax exemption to $15 million, leaving estate values below that level untaxed before being distributed to inheritors

- A small increase to the Standard Deduction and to the cutoff levels for the bottom two income tax brackets relative to current policy

- Increases to the deduction for qualified business income for personal income taxes

- New limits on itemized deductions for the highest income earners, adding a charitable deduction for non-itemizers, and an increase in the deductible share of qualifying Child and Dependent Care tax credit costs

- Temporary deductions, ending after Tax Year 2028, for tipped income, certain overtime payments, qualifying automobile loan interest payments, for state and local taxes paid, and for people over age 64 years, with limits or phaseouts at certain income thresholds and caps on deduction amounts for all of these temporary tax provisions

- Modifications to some international corporate tax provisions while permanently extending others, and providing permanent or temporary extensions or enhancements to certain business depreciation and cost deduction provisions, as well as the Low Income Housing Tax Credit

The net result of these tax changes, based on analyses conducted by the U.S. Congressional Budget Office, the Tax Policy Center, the University of Pennsylvania, and the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, would likely be to reduce taxes for filers with higher incomes by large amounts, while providing tax reductions for households with lower incomes that, in many instances, will likely not offset the benefit reductions in the new law.[15]

The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy estimated the effects of the tax law changes only in every state, including New Hampshire.[16] Granite State households in the lowest 20 percent by income, with incomes below $37,000 per year, will receive an average tax reduction of $200 in 2026. Households with incomes from $72,300 to $117,900, in the middle 20 percent of the income scale, will see an average federal income tax reduction of $2,660. For households with incomes above $894,700, or the top one percent, the average tax reduction will be $59,170.

For context, the median income was about $53,800 among the approximately 157,000 households that rented their homes in New Hampshire during 2023.[17] This modeling suggests that, under the reconciliation law in 2026, the estimated tax reduction for the average taxpayer in the top one percent of the income scale will be approximately equivalent to the entire 2023 median income for a Granite State renter household.

Medicaid and Other Health Policy Changes

The largest reductions in expenditures from the reconciliation law relative to projected spending under prior law during the next ten years are in the Medicaid program. Changes to Medicaid are projected to reduce expenditures by about $990 billion during Federal Fiscal Years 2025 through 2034 relative to expectations under prior law.[18]

While the impacts on Medicaid funding will vary based on the actions of individuals enrolled or seeking to enroll in the program, State policymaker decisions related to funding and eligibility, and the economy, analysis from KFF projected federal spending on Medicaid in New Hampshire would fall an estimated 15 percent, or approximately $2.3 billion, during the next ten years relative to prior policy.[19]

Medicaid Work Requirements

The largest changes in Medicaid spending would be due to expected disenrollments following the implementation of a work requirement for Medicaid. The federal government will require states to have a work requirement for most Medicaid Expansion enrollees, age 19 to 64, by January 2027.[20] In New Hampshire, Medicaid Expansion is known as the Granite Advantage Health Care Program, and had 58,321 participating Granite Staters at the end of June 2025.[21]

The work requirements stipulate that enrollees must complete 80 hours per month of employment, qualifying community service activities, participation in work or educational programs, or some combination of those activities to fulfill the requirements. These requirements need to be satisfied for at least one month before enrolling in Medicaid and at least one month in every six months, which is the more frequent timeline during which Medicaid redeterminations are required under the reconciliation law. However, state governments have the flexibility to make the number of months required larger, potentially requiring ongoing enrollees to provide evidence they have met the requirement during every month.

Exemptions to the work requirements include:[22]

- Parents or other guardians of dependent children who are under 14 years old or who have a disability

- Any individual who is medically frail, who has special medical needs or complex medical conditions, or who is blind

- Individuals who have a disability that meets a certain federal definition, an intellectual or developmental disability that significantly impacts daily living, a disabling mental health condition, or who are Veterans with a qualifying disability status

- Individuals with a substance use disorder or who are in a drug addiction or alcoholic treatment and rehabilitation program

- People in households receiving Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits and who are not exempt from the work requirements in that program

- Individuals who are pregnant or receiving postpartum care

- Former foster youth

While the volume of disenrollments will depend on both the behavior of individuals and State policymakers, these new requirements will lead to disenrollments, primarily due to reporting requirements. A May 2025 publication from KFF estimated that 63 percent of Granite State adults age 19 to 64 on Medicaid and not enrolled in programs designed to assist individuals with disabilities were working either full time or part time in 2023.[23] In 2018-2019, when Medicaid work requirements were implemented in Arkansas and when they began to be implemented in New Hampshire, both states found that many disenrollments or potential disenrollments were due to a lack of information from enrollees, rather than evidence that program participants were not working.[24]

The U.S. Congressional Budget Office estimated, based on the U.S. House’s version of the bill, that the work requirements would lead to 5.2 million fewer people being enrolled in Medicaid in 2034, and 4.8 million more people without any form of health coverage.[25] Based on the final version of the reconciliation law, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimated 9.9 million to 14.9 million people would be at risk of losing Medicaid coverage due to the work requirements, and that 7.1 million could be disenrolled if the experience in Arkansas provides accurate guidance, by 2034.[26]

In New Hampshire, an estimated 20,000 people, or about 35 percent of Medicaid Expansion enrollees under these projections, will lose coverage due to the work requirement, according to the Cetner on Budget and Policy Priorities. This level of disenrollment will occur even though only an estimated 14 percent of enrollees will be either not working or not qualify for an exemption, according to the projections.[27]

New Hampshire’s new State Budget requires the State to seek a waiver from the federal government to implement the work and community engagement requirements that the State began using in 2019 before it abandoned the initiative because of about 17,000 pending disenrollments.[28] However, the limitations the new federal law places on waivers may limit the State’s ability to deviate from the work requirement framework established in federal law; the State would be able to implement the federal work requirements, and would have certain flexibilities for more expansive compliance requirements based on the number of months checked, but would face other restrictions on expanding work requirements under the new reconciliation law.[29]

Researchers examining the effects of Medicaid work requirements in Arkansas found health coverage decreased but did not identify a significant change in employment.[30]

Ineligibility for Legal Immigrants

Many immigrants who are lawfully present in the United States, including refugees and asylees, who are currently eligible for Medicaid will no longer be eligible under the new reconciliation law after October 2026. Prior law generally required that legal immigrants be in the United States for at least five years before becoming fully eligible for Medicaid; undocumented immigrants are not eligible for Medicaid benefits. Some legal immigrants, however, were eligible upon entry if they faced certain conditions and met all other Medicaid criteria.

Starting October 2026, legal immigrants who will become ineligible for Medicaid, regardless of length of residency, will include people who have entered the United States legally as refugees, asylees, victims of human trafficking or domestic violence, certain people who have been permitted for humanitarian reasons, individuals from Iraq and Afghanistan with special immigrant visas, and all other legal immigrants who do not fall into specific categories.

The groups that will remain eligible include those admitted for permanent residence who have “green cards” after waiting for five years, certain Cuban and Haitian migrants, immigrants who are citizens of nations from the Compact of Free Association (including the Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, and the Republic of Palau), and children and pregnant women. All other lawful immigrants become ineligible for Medicaid and, 18 months after enactment, Medicare under the new reconciliation law.[31]

States and hospitals will also lose Medicaid reimbursement for providing care to people who are seeking emergency medical services and would be eligible for Medicaid except for their immigration status. Only states with Medicaid Expansion will lose this funding, one of several instances in which the new law reduces funding for the 40 states, including New Hampshire, that have adopted Medicaid Expansion relative to the ten states that have not.[32]

Copayment Requirements and Limiting Retroactive Eligibility

The new reconciliation law requires that states must require Medicaid Expansion enrollees with incomes above the federal poverty line to provide a copayment of up to $35 for every non-exempt service received. Certain services, including emergency room, pediatric and pregnancy-related, family planning, primary, mental health, substance use disorder, Federally Qualified Health Center, rural health clinic, and certified community behavior health services, will be exempt from the co-payment requirement. Prescription drug copayments will be required. States are permitted to allow providers to deny services to non-exempt Medicaid Expansion enrollees who cannot pay the copayments. New Hampshire’s new State Budget required the State to seek permission to implement premiums for certain Medicaid enrollees, but the new reconciliation law appears to forbid states from charging premiums.[33]

Retroactive eligibility will also be limited relative to prior policy. Federal law previously allowed services being received, such as for an individual with a significant medical event or who entered nursing facility care without Medicaid coverage, to be paid for retroactively up to 90 days before an individual is determined to be Medicaid eligible. The new reconciliation limits this period to 30 days for Medicaid Expansion adults and 60 days for all other enrollees.[34]

Limits on Provider Taxes

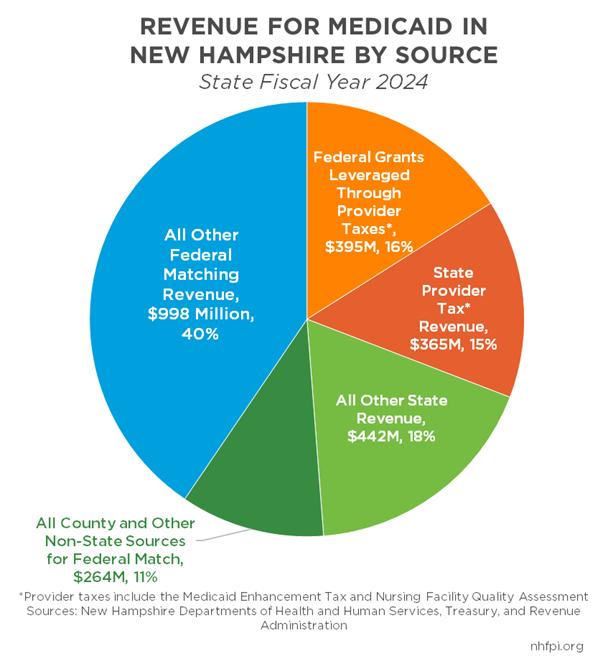

Since the 1980s, many states have charged taxes on certain health care providers and used those tax revenues to access federal Medicaid dollars. Those resources can then be used to support Medicaid services, including reimbursements to providers. The maximum provider tax rate permitted under federal law is 6.0 percent.[35]

New Hampshire has two large provider taxes. The Medicaid Enhancement Tax, established in 1991, taxes hospitals at 5.4 percent of net patient services revenue and collected $319.9 million in State Fiscal Year (SFY) 2024, which made it the fourth-largest State tax revenue source. The Nursing Facility Quality Assessment, created in 2004, taxes nursing facilities at a 5.5 percent rate and collected $44.8 million in SFY 2024.[36] Together, these taxes generated State and federal revenues for Medicaid services in New Hampshire totaling approximately $759.8 million in SFY 2024, or about 30.8 percent of the total Medicaid federal, State, county, and other expenditures of $2.464 billion during SFY 2024.[37]

Under the new reconciliation law, states with Medicaid Expansion will not be able to raise or implement new provider taxes. Starting in October 2027, the maximum provider tax rate will be limited to 5.5 percent, and then will be required to drop by half a percentage point each year until falling to 3.5 percent in October 2031, which will be the new maximum rate from that time forward. This limitation will not apply to nursing and intermediate care facilities, so it may only impact New Hampshire’s Medicaid Enhancement Tax.[38] If the Medicaid Enhancement Tax rate had been 3.5 percent in SFY 2024, total tax revenues would have been $133.3 million lower, likely forfeiting about $146.0 million in federal revenue for Medicaid services unless another revenue source had been used to provide that match.

The total reduction in federal spending due to this provider tax provision nationally, according to the U.S. Congressional Budget Office, will be $191.1 billion over ten years.[39]

Aid for Rural Hospitals

To help address concerns about the impacts of Medicaid reductions on rural hospitals, the new reconciliation law includes a new Rural Health Transformation Program. The Program’s funding will provide the equivalent of about 37 percent of the estimated reduction in federal funding to rural areas, according to KFF.[40]

This Program will appropriate $10 billion a year for five years, of which states will receive half, divided equally among the states, in payments if they have approved rural health transformation plans submitted. These plans will include improvements to hospital access and health services in rural areas, prioritizing use of data- and technology-driven solutions to both rural hospital challenges and chronic disease management, enhancing opportunities for health care clinicians, and fostering strategic partnerships between rural hospitals and other health care providers. Funds must be used for a set array of purposes, including payments to providers, chronic illness management, access to substance use disorder and mental health treatments, technology-driven and innovative models for health care delivery, and supporting the rural health care workforce.[41]

The remaining half will be provided by the federal government based on applications for additional funds made by states. Much of the control over the distribution of these funds is given to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Administrator of the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Under the law, CMS has broad discretion as to where and how to deploy these funds, particularly the funds outside of the half that is to be distributed equally to states with approved baseline applications. There is not a reporting requirement, nor necessarily a requirement that these funds be used solely in rural areas, and “rural” is not defined in the new statute.[42]

Marketplace Assistance Changes

The federally-sanctioned marketplaces, operating in each individual state, are a result of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Many marketplace participants receive subsidies through tax credits to help them pay for premiums, particularly participants with low incomes. In 2024, the estimated total amount of premium tax credits received by marketplace participants in New Hampshire was $191.9 million.[43]

As with Medicaid eligibility, the new reconciliation law makes many legal immigrants who are currently eligible for premium assistance tax credits to help them afford individual plans on the health insurance marketplace ineligible for that aid. These subsidies will end for all legal immigrants, including refugees, approved asylees, victims of human trafficking and domestic violence, valid via holders, and people with Temporary Protected Status, except for lawful permanent residents with “green cards,” Cuban and Haitian migrants under certain conditions, and Compact of Free Association citizens.

The new law also ends automatic re-enrollment for marketplace participants, which was used by 54 percent of individuals participating last year. Provisional eligibility for marketplace assistance will also end, and the government will be required to deny assistance to individuals who have not filed proper paperwork with the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. These provisions could be triggered by paperwork processing delays at the Internal Revenue Service, which has lost 26 percent of its staff since January 2025.[44]

The new reconciliation law also ends a federal rule that permitted people with incomes below 150 percent of the federal poverty guidelines to enroll in marketplace coverage at any time of year. This provision alone would reduce federal spending by an estimated $39.5 billion nationally over ten years.[45]

The new law does not extend enhancements to marketplace premium assistance tax credits that are due to end after 2025.[46]

Other Health Changes

The new reconciliation law makes many other changes to federal health policy, including:[47]

- Requiring redetermination of eligibility for Medicaid Expansion enrollees every six months, rather than the every 12 months required under prior law

- Halting the implementation of components of new federal rules that would have made application processes for Medicaid more efficient and required more staffing at nursing facilities

- Increasing the permissible uses of Health Savings Accounts, where individuals can store and spend resources without being taxed on contributions, earnings, or withdrawals

- Excluding certain drugs from required Medicare drug price negotiations that were created in the 2022 federal Inflation Reduction Act

Food Assistance Cost Sharing and Work Requirement Changes

The new reconciliation law will reduce federal funding for food assistance through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) by more than $180 billion, or about 20 percent relative to projections under prior law, from 2025 through 2034.[48]

SNAP benefits provide help to individuals and families with incomes below twice the poverty threshold to afford food, including 76,934 people in New Hampshire at the end of June 2025.[49] The maximum permissible SNAP benefit in New Hampshire during 2024 was about $2.83 per person per meal.[50]

Prior to the reconciliation law, the federal government paid 100 percent of the cost of SNAP benefits, while administrative costs of implementation were split approximately evenly between the federal and state governments. Total reported federal expenditures on benefits for Granite Staters was $154.3 million during Federal Fiscal Year 2024.[51]

Cost Sharing with States

The federal government calculates error rates in SNAP benefit payments in each state. These rates measure underpayments and overpayments in state-level SNAP. Under the new reconciliation law, states with error rates above 6 percent would have to pay some portion of the cost of the program, ranging from 5 percent to 15 percent of the benefit costs, depending on the error rate.

New Hampshire’s error rate in 2024 was 7.57 percent. The Granite State’s error rate has ranged from 3.01 percent to 12.53 percent in the years since 2003, but only one U.S. state, South Dakota, has never had an error rate above 6 percent during that period. With a 7.57 percent error rate, New Hampshire would be expected to pay about $8 million for its share of SNAP benefits in 2028, according to estimates from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. With the 2023 error rate of 12.53 percent, New Hampshire would have to pay an estimated $23 million.[52]

States will also be responsible for about 75 percent of administrative costs for SNAP, rather than about 50 percent, under the new law.

Limiting Future Benefit Increases

The new reconciliation law also caps future increases in the calculations of benefits, which are tied to the federal government’s Thrifty Food Plan. Benefits would be tied to overall consumer inflation, and limit the extent to which the federal government can re-evaluate the Thrifty Food Plan’s cost based on food prices, consumption patterns, dietary guidance, and food composition data. Future changes are required to be cost-neutral under the new law. Benefits would also be capped for very large households. Food prices are often more volatile, and may be more dependent on energy prices, than is reflected in overall consumer inflation.[53]

Expanded Work Requirements and Ineligibility for Lawful Immigrants

Work requirements currently exist in SNAP, and the new reconciliation law expands those requirements. SNAP enrollees who do not comply with a 20 hour per week work or training requirement, who are able-bodied, and who are between the ages of 19 and 54 years can have three months of noncompliance with work requirements in a 36-month period before being disenrolled. Some individuals are exempt, including people in households with children, people unable to work because of their physical or mental health, people who are pregnant, former foster youth up to age 24, Veterans, and people experiencing homelessness.[54]

Under the new reconciliation law, the work requirement is expanded to include adults age 55 to 64, to parents of children who are at least 14 years old, and to Veterans, people experiencing homelessness, and former foster youth. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimated, for a version of the bill in the Senate, that about 4,000 people in New Hampshire would be newly subject to the work requirements and at risk of losing SNAP benefits because of these new provisions.[55]

As with Medicaid and Medicare, certain immigrants lawfully in the United States will also become ineligible for SNAP food assistance under the new law, including refugees, asylees, and survivors of trafficking or domestic violence.

Energy Initiative Eliminations

Changes to energy, manufacturing, and other tax credits, which were either established or enhanced in the 2022 federal Inflation Reduction Act, are projected to reduce federal expenditures by $540 billion relative to projected amounts from prior law over the next ten years.[56]

The significant cost savings stems from several key provisions that will impact Granite Staters, including:[57]

- The termination of tax credits for new and used electric vehicle purchases at the end of September 2025, including for individual and commercial consumers, which is projected to reduce expenditures by $189 billion during the next ten years

- Ending, between December 2025 and June 2026, the tax credits for energy efficiency improvements in homes and commercial buildings and the residential clean energy credit, the last of which 19,880 tax filers in New Hampshire used for Tax Year 2022[58]

- A phaseout of clean electricity investment and production tax credits starting in 2032, except for wind and solar, for which the credit is unavailable for facilities that do not begin construction after July 4, 2026

- Rescinding funding for federal offices designed to facilitate state-based energy efficiency trainings, the siting of interstate electricity transmission lines, offshore wind energy planning and analysis, and advanced technology vehicle manufacturing

Higher Education Funding Changes

The new reconciliation law is projected to reduce spending on education-related programs by about $295 billion, relative to projections under prior law, between 2025 and 2034. Most of these savings come from changes in policies related to student loans.[59]

The new law creates two new loan repayment plans for all loans that are made after July 1, 2026. The standard plan that would require fixed monthly payments over time horizons ranging from ten to 25 years, depending on the size of the loan. A Repayment Assistance Plan, newly established by this law, will calculate amounts owed based on the borrower’s income, requiring at least $50 of principal is paid down per month but would include subsidies to help with unpaid interest. Borrowers could switch from the Assistance Plan to the standard plan at any time.

Student loans will be limited to $100,000 for graduate programs and $200,000 for professional programs. There are also lower loan limits for part-time school attendees, and institutions can implement their own borrowing limits as well.

Loans will also be prohibited to undergraduate programs for which the majority of program graduates earn less than the median 25-to-34-year-old high school graduate, or high school-equivalent educational attainment, in their state. Loans will be prohibited for graduate programs that do not produce a majority of graduates earning more than the median bachelor’s degree holder in their state in a similar field as well.

Pell grant eligibility will be removed for students who receive full-ride scholarships, although Pell Grant access will be expanded through new “Workforce Pell Grants” that align with high-skill, high-wage, and in-demand industry sectors or occupations, as identified by the state’s governor.

The new law also expands uses of tax-free 529 plans to cover more elementary, secondary, home school, and postsecondary credential expenses.[60]

Historically, graduates of four-year higher education institutions in New Hampshire have had some of the highest debt loads among their peers graduating from institutions in other states.[61]

Boosts to Defense and Immigration Enforcement Spending

The new reconciliation law includes significant investments in defense spending, totaling a projected $149.5 billion in estimated expenditures above baseline during the Federal Fiscal Years 2025-2034 timeframe. These appropriations include $27.6 billion for shipbuilding, $23.8 billion for the munitions and defense industrial base, $23.2 billion for air and missile defense, $15.5 billion for military readiness, $15.4 billion for low cost weapons across at least 33 different organizations or projects, and $13.2 billion for nuclear forces.[62] During Federal Fiscal Year 2024, U.S. Department of Defense contracts accounted for about $2.15 billion in newly-obligated funds for activities to be performed in New Hampshire, including contracts with BAE Systems and Sig Sauer.[63]

The law also appropriates $176 billion for international border security and immigration-related enforcement activities. That includes $51 billion for building a border wall and other border security infrastructure and facilities, $45 billion for more U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention capacity, $32 billion for increased Department of Homeland Security funding that includes boosts to ICE operations, $12.6 billion to fund state and local assistance from the Department through 2029 and establishing a “State Border Security Reinforcement Fund,” and $12.0 billion for U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Appropriations for border security technology upgrades include references to the northern border, but do not make any specific appropriations to New Hampshire’s border with Canada.[64]

For context, the entire ICE budget for Federal Fiscal Year 2025 was $10.4 billion, making the appropriation for ICE detention facilities more than four times the agency’s operating budget for this fiscal year; the $29.85 billion appropriation made specifically for ICE for recruiting, hiring, and compensating personnel, facility upgrades, transportation, legal costs, funding the Victims of Immigration Crime Engagement Office, and “family unity” efforts would be an additional nearly three times increase over the Federal Fiscal Year 2025 budget for ICE.[65]

Future Impacts and State Flexibilities

With a wide array of policies touching many facets of government operations, the new reconciliation law’s impacts are difficult to project with precision, including its effects on the well-being of Granite Staters. However, the law’s provisions appear to shift resources from individuals and families with lower incomes to those with higher incomes through tax reductions favoring higher-income households while reducing funding for food and medical assistance programs. Economic modeling suggests that assistance to households with few resources is more economically stimulative than tax reductions for people who have the benefit of higher incomes.[66]

The impacts of the bill will also be determined by subsequent policy choices. State policymakers have consequential flexibility to implement components of the Medicaid work requirement and a new subset of Pell Grants as they choose, while reductions in SNAP benefits may prompt changes to the program at the State level. Federal Executive Branch policymakers also have substantial flexibility over some key appropriations, such as funding that could be used to support rural hospitals and significant increases in defense and immigration enforcement spending. As with the 2021 reconciliation-enabled passage of the American Rescue Plan Act before it, the changes made by the 2025 reconciliation law will continue to have substantial impacts in New Hampshire for many years after its enactment.[67]

End Notes

[1] To read the new law, see H.R. 1 – One Big Beautiful Bill Act on the Congress.gov website. To learn more about the reconciliation process, see the U.S. Congressional Research Service’s March 6, 2025 report The Reconciliation Process: Frequently Asked Questions.

[2] For more details, see the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy’s Analysis of Tax Provisions in the Senate Reconciliation Bill: National and State Level Estimates, as updated July 2, 2025.

[3] For more analysis of the impacts of particular provisions see the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget’s analysis of the U.S. Congressional Budget Office’s reported expenditures, What’s In the One Big Beautiful Bill Act?, July 22, 2025. The $5.36 billion figure was derived from this analysis, which is based on U.S. Congressional Budget Office projections.

[4] See the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s July 22, 2025 report Medicaid, CHIP, and Affordable Care Act Marketplace Cuts and Other Health Provisions in the Budget Reconciliation Law, Explained.

[5] See more details in the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget’s analysis of the U.S. Congressional Budget Office’s reported expenditures, What’s In the One Big Beautiful Bill Act?, July 22, 2025.

[6] See the U.S. Congressional Budget Office’s July 21, 2025 publication Estimated Budgetary Effects of Public Law 119-21, to Provide for Reconciliation Pursuant to Title II of H. Con. Res. 14, Relative to CBO’s January 2025 Baseline.

[7] See more details in the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget’s analysis of the U.S. Congressional Budget Office’s reported expenditures, What’s In the One Big Beautiful Bill Act?, July 22, 2025.

[8] See the Tax Foundation’s July 9, 2025 analysis The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act and the July 8, 2025 University of Pennsylvania Penn Wharton Budget Model analysis President Trump-Signed Reconciliation Bill: Budget, Economic, and Distributional Effects.

[9] For examples of these analyses, see the July 8, 2025 University of Pennsylvania Penn Wharton Budget Model analysis President Trump-Signed Reconciliation Bill: Budget, Economic, and Distributional Effects, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy’s Analysis of Tax Provisions in the Senate Reconciliation Bill: National and State Level Estimates from July 2, 2025, the Tax Policy Center’s July 3, 2025 analysis Distributional Effects of the Tax Provisions in the 2025 Budget Reconciliation Act, and the U.S. Congressional Budget Office May 20, 2025 analysis of the similar, but not identical, version of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act that was considered by the U.S. House.

[10] Read more about the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in NHFPI’s December 2017 analysis Congress May Reduce Funding to Key Programs Following Tax Changes.

[11] Read more about the Child Tax Credit in NHFPI’s analysis of the 2021 expansion, which was temporary and much larger than either the TCJA or One Big Beautiful Bill Act expansions, in the March 2022 Issue Brief Expansions of the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit in New Hampshire.

[12] Read more about the impacts of the TCJA in New Hampshire in NHFPI’s September 26, 2024 analysis Federal Policymakers Will Consider Tax Changes Benefitting Higher-Income Granite Staters in 2025.

[13] For analyses of the tax provisions in the new reconciliation law, see the July 8, 2025 University of Pennsylvania Penn Wharton Budget Model analysis President Trump-Signed Reconciliation Bill: Budget, Economic, and Distributional Effects and the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy’s Analysis of Tax Provisions in the Senate Reconciliation Bill: National and State Level Estimates, as updated July 2, 2025. For more details on housing-related provisions, see the Bipartisan Policy Center’s July 1, 2025 explainer 2025 Reconciliation Debate: Senate Housing Provisions. For more information on the state and local tax deduction, see the Bipartisan Policy Center’s June 9, 2025 post How Does the 2025 Tax Law Change the SALT Deduction?

[14] Read more about the 2021 Child Tax Credit expansion in NHFPI’s March 2022 Issue Brief Expansions of the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit in New Hampshire.

[15] See the July 8, 2025 University of Pennsylvania Penn Wharton Budget Model analysis President Trump-Signed Reconciliation Bill: Budget, Economic, and Distributional Effects for the full impacts of the law’s provisions by income group. The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy’s Analysis of Tax Provisions in the Senate Reconciliation Bill: National and State Level Estimates from July 2, 2025 provides analysis showing that the estimated tax change from new federal tariffs could more than offset tax reductions for households with moderate and low incomes. The Tax Policy Center, a joint project of the Urban Institute and the Brookings Institution, analyzed the changes in after tax income for many of the tax policy changes for both 2026 and 2030, the latter of which was after many of the temporary tax provisions expire, in the July 3, 2025 publication Distributional Effects of the Tax Provisions in the 2025 Budget Reconciliation Act. The U.S. Congressional Budget Office analyzed the tax and benefit changes for the similar, but not identical, version of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act that was considered by the U.S. House in a May 20, 2025 report.

[16] For the full analysis, see the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy’s July 7, 2025 report Analysis of Tax Provisions in the Trump Megabill as Signed into Law: National and State Level Estimates, updated July 22, 2025.

[17] For median renter household income, see the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, Table S2503.

[18] See the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s July 22, 2025 report Medicaid, CHIP, and Affordable Care Act Marketplace Cuts and Other Health Provisions in the Budget Reconciliation Law, Explained.

[19] See the KFF July 23, 2025 analysis Allocating CBO’s Estimates of Federal Medicaid Spending Reductions Across the States: Enacted Reconciliation Package.

[20] For more details about the work requirement, see the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s July 22, 2025 report Medicaid, CHIP, and Affordable Care Act Marketplace Cuts and Other Health Provisions in the Budget Reconciliation Law, Explained and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities July 22, 2025 Research Note Medicaid Work Requirements Will Take Away Coverage From Millions: State and Congressional District Estimates.

[21] For more information on the New Hampshire Granite Advantage Health Care Program, see NHFPI’s January 17, 2023 Issue Brief The Effects of Medicaid Expansion in New Hampshire. Medicaid enrollment data in New Hampshire is reported monthly by the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services; data cited for June 2025 enrollment provided in the Department’s caseload report.

[22] See the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s July 22, 2025 report Medicaid, CHIP, and Affordable Care Act Marketplace Cuts and Other Health Provisions in the Budget Reconciliation Law, Explained and the text of the new reconciliation law, Public Law Number 119-21.

[23] See KFF’s May 30, 2025 Issue Brief and Appendix Understanding the Intersection of Medicaid and Work: An Update. Note that the KFF May 2025 Fact Sheet Medicaid in New Hampshire identifies that 75 percent of Medicaid adults in New Hampshire were working either part time or full time; those statistics were not described in the table in the detailed report.

[24] For more information on New Hampshire’s work requirement implementation in 2019, see NHFPI’s May 5, 2025 analysis Up to 19,000 Granite Staters Could Lose Medicaid Coverage Under Potential Federal Work Requirements. For more analysis of the experience with Medicaid work requirements in New Hampshire, see the Urban Institute’s February 2020 research report New Hampshire’s Experiences with Medicaid Work Requirements: New Strategies, Similar Results. See also NHFPI’s May 20, 2019 Issue Brief Medicaid Work Requirements and Coverage Losses.

[25] See the U.S. Congressional Budget Office’s June 4, 2025 letter Re: Estimated Effects on the Number of Uninsured People in 2034 Resulting From Policies Incorporated Within CBO’s Baseline Projections and H.R. 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.

[26] See the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities July 22, 2025 Research Note Medicaid Work Requirements Will Take Away Coverage From Millions: State and Congressional District Estimates.

[27] See the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities July 22, 2025 Research Note Medicaid Work Requirements Will Take Away Coverage From Millions: State and Congressional District Estimates.

[28] See NHFPI’s July 28, 2025 report The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2026 and 2027.

[29] See the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s July 22, 2025 report Medicaid, CHIP, and Affordable Care Act Marketplace Cuts and Other Health Provisions in the Budget Reconciliation Law, Explained.

[30] See the New England Journal of Medicine’s June 2019 Special Report Medicaid Work Requirements — Results from the First Year in Arkansas, the Urban Institute’s April 2025 analysis New Evidence Confirms Arkansas’s Medicaid Work Requirement Did Not Boost Employment, and the U.S. Congressional Budget Office’s June 9, 2022 report Work Requirements and Work Supports for Recipients of Means-Tested Benefits.

[31] For more details about eligibility changes for immigrants, see the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s July 22, 2025 report Medicaid, CHIP, and Affordable Care Act Marketplace Cuts and Other Health Provisions in the Budget Reconciliation Law, Explained.

[32] See the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s July 22, 2025 report Medicaid, CHIP, and Affordable Care Act Marketplace Cuts and Other Health Provisions in the Budget Reconciliation Law, Explained.

[33] For details about the New Hampshire State Budget, see NHFPI’s July 28, 2025 report The State Budget for Fiscal Years 2026 and 2027. For more details about the federal reconciliation law, see the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s July 22, 2025 report Medicaid, CHIP, and Affordable Care Act Marketplace Cuts and Other Health Provisions in the Budget Reconciliation Law, Explained.

[34] See the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s July 22, 2025 report Medicaid, CHIP, and Affordable Care Act Marketplace Cuts and Other Health Provisions in the Budget Reconciliation Law, Explained.

[35] For more information on provider taxes, see the U.S. Congressional Research Service’s December 2024 report Medicaid Provider Taxes and KFF’s June 2017 analysis States and Medicaid Provider Taxes or Fees.

[36] For this information and more related to provider taxes in New Hampshire, see the New Hampshire Department of Revenue Administration’s 2024 Annual Report and NHFPI’s July 2025 presentation Funding Public Services in New Hampshire.

[37] These NHFPI calculations, based on Medicaid expenditures reported by the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, assumes a 50-50 federal match with revenues raised through the Medicaid Enhancement Tax and the Nursing Facility Quality Assessment as reported by the Department of Revenue Administration. However, for the approximately $3.8 million in Medicaid Enhancement Tax revenue, as reported by the New Hampshire Treasury Department, that funds the non-federal share of Medicaid Expansion, a 90-10 federal match is assumed for the calculations.

[38] See the Hilltop Institute’s July 1, 2025 publication What’s the Impact of Phasing Provider Taxes Down to 3.5% for Medicaid Expansion States? and the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s July 22, 2025 report Medicaid, CHIP, and Affordable Care Act Marketplace Cuts and Other Health Provisions in the Budget Reconciliation Law, Explained.

[39] See the U.S. Congressional Budget Office’s July 21, 2025 publication Estimated Budgetary Effects of Public Law 119-21, to Provide for Reconciliation Pursuant to Title II of H. Con. Res. 14, Relative to CBO’s January 2025 Baseline.

[40] See KFF’s July 24, 2025 analysis A Closer Look at the $50 Billion Rural Health Fund in the New Reconciliation Law.

[41] See Section 71401 of PL 119-21.

[42] See KFF’s July 24, 2025 analysis A Closer Look at the $50 Billion Rural Health Fund in the New Reconciliation Law and the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s July 28, 2025 webinar Budget Reconciliation (HR1) Medicaid and Marketplace Provisions.

[43] See KFF’s Estimated Total Premium Tax Credits Received by Marketplace Enrollees.

[44] See The Brookings Institution’s July 17, 2025 commentary The new tax bill burdens an already overburdened IRS and the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s July 22, 2025 report Medicaid, CHIP, and Affordable Care Act Marketplace Cuts and Other Health Provisions in the Budget Reconciliation Law, Explained.

[45] See the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy’s July 22, 2025 report Medicaid, CHIP, and Affordable Care Act Marketplace Cuts and Other Health Provisions in the Budget Reconciliation Law, Explained.

[46] For more information on the enhanced marketplace tax credits, see KFF’s July 26, 2024 report Inflation Reduction Act Health Insurance Subsidies: What is Their Impact and What Would Happen if They Expire?

[47] For a comprehensive list of health policy provisions in the new reconciliation law, including the changes made between the House and Senate versions and comparisons to current law, see the KFF resource Health Provisions in the 2025 Federal Budget Reconciliation Bill updated July 8, 2025.

[48] Basing figures off of the U.S. Congressional Budget Office, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reported $187 billion in reduced spending, as well as the 20 percent reduction compared to expected funding. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget’s breakdown of the reconciliation law identified $182 billion in reductions specifically in SNAP in its high-level summary.

[49] Income threshold applies to New Hampshire due to expanded categorical eligibility, but other states have different thresholds. Enrollment data from the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services July 2, 2025 caseload statistics report.

[50] See the Urban Institute’s Data Tool, updated July 16, 2025, Does SNAP Cover the Cost of a Meal in Your County?

[51] See the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service SNAP Data Tables website, accessed August 1, 2025.

[52] See the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities June 30, 2025 Research Note: Senate Republican Leaders’ Proposal Risks Deep Cuts to Food Assistance, Some States Ending SNAP Entirely and policy brief By the Numbers: Harmful Republican Megabill Takes Food Assistance Away From Millions of People.

[53] See Section 10101 of Public Law 119-21. See also the National Center of Children in Poverty’s What the 2025 Reconciliation Bill’s SNAP Overhauls Could Mean for Children, Families, and States.

[54] See the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities September 2024 publication A Quick Guide to SNAP Eligibility and Benefits.

[55] See the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities policy brief By the Numbers: Harmful Republican Megabill Takes Food Assistance Away From Millions of People and June 27, 2025 analysis Senate Agriculture Committee’s Revised Work Requirement Would Risk Taking Away Food Assistance From More Than 5 Million People: State Estimates.

[56] These figures were presented by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget’s analysis of the U.S. Congressional Budget Office’s reported expenditures, What’s In the One Big Beautiful Bill Act?, July 22, 2025.

[57] For more information, see the Bipartisan Policy Center’s July 28, 2025 explainer 2025 Reconciliation Debate: Senate Energy Provisions.

[58] See the U.S. Internal Revenue Service’s Individual Income Tax State Data for Tax Year 2022, the most recent published as of August 1, 2025.

[59] See the nonprofit Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget’s July 22, 2025 analysis of the U.S. Congressional Budget Office’s reported expenditures titled What’s In the One Big Beautiful Bill Act?

[60] For more information on education-related provisions in the reconciliation law, see the National Conference of State Legislature’s July 7, 2025 Tracking the 2025 Budget Reconciliation Process resource and Public Law 119-21.

[61] For more information, see NHFPI’s November 16, 2023 Issue Brief Limited State Funding for Public Higher Education Adds to Workforce Constraints.

[62] See the U.S. Congressional Budget Office’s July 21, 2025 publication Estimated Budgetary Effects of Public Law 119-21, to Provide for Reconciliation Pursuant to Title II of H. Con. Res. 14, Relative to CBO’s January 2025 Baseline and Section 20005 of Public Law 119-21.

[63] For more information on federal funds in New Hampshire, see NHFPI’s May 28, 2025 Issue Brief Federal Funding and Employment in New Hampshire.

[64] See the U.S. Congressional Budget Office’s July 21, 2025 publication Estimated Budgetary Effects of Public Law 119-21, to Provide for Reconciliation Pursuant to Title II of H. Con. Res. 14, Relative to CBO’s January 2025 Baseline, Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget’s July 22, 2025 analysis of the U.S. Congressional Budget Office’s reported expenditures, What’s In the One Big Beautiful Bill Act?, and Section 90004 of Public Law 119-21.

[65] See the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Budget Overview for Fiscal Year 2026. See also Sections 90003 and 100052 of Public Law 119-21.

[66] See NHFPI’s 2025 New Hampshire Policy Points, the Conclusion chapter and the Funding Public Services chapter endnote 58.

[67] Read more about the American Rescue Plan Act in New Hampshire in NHFPI’s March 26, 2021 blog Federal American Rescue Plan Act Directs Aid to Lower-Income Children, Unemployed Workers, and Public Services.

These articles are being shared by partners in the Granite State News Collaborative. For more information, visit collaborativenh.org.