Above: South Street in Milford recently underwent road widening. Courtesy of the town of Milford.

Above: South Street in Milford recently underwent road widening. Courtesy of the town of Milford.

Milford, settled in 1794 and nestled in the six-town hub of the Souhegan Valley, epitomizes what many young families yearn for in a New England village: a vibrant downtown with an architectural nod to the past, close proximity to Boston and a tranquil small-town feel.

Plenty of people are looking for homes in Milford, says Melanie Zaharias of Zaharias Real Estate in Milford, but fewer can afford them as inventory is tight, and prices keep rising. Abutting more affluent towns like Amherst and Bedford, Milford used to be a less expensive alternative but total assessed value in this working-class town spiked by nearly $300 million, or 24%, in the last five years.

Lincoln Daley, Milford’s community development director, says developers and home buyers are taking notice. In 2018, the town issued 74 permits for new construction of single-family homes, more than any other municipality in NH.

Real estate developer Kenneth Lehtonen of San-Ken Homes created a 54-lot community on a foreclosed 174-acre parcel of land in Milford that he branded “Autumn Oaks.” Milford was a reasonable real estate gamble when he launched the project four years ago, but Lehtonen never imagined home prices reaching the half-million-dollar mark. “[Milford’s real estate] actually has grown, and values have grown higher than we could have expected,” he says, noting only a handful of lots remain.

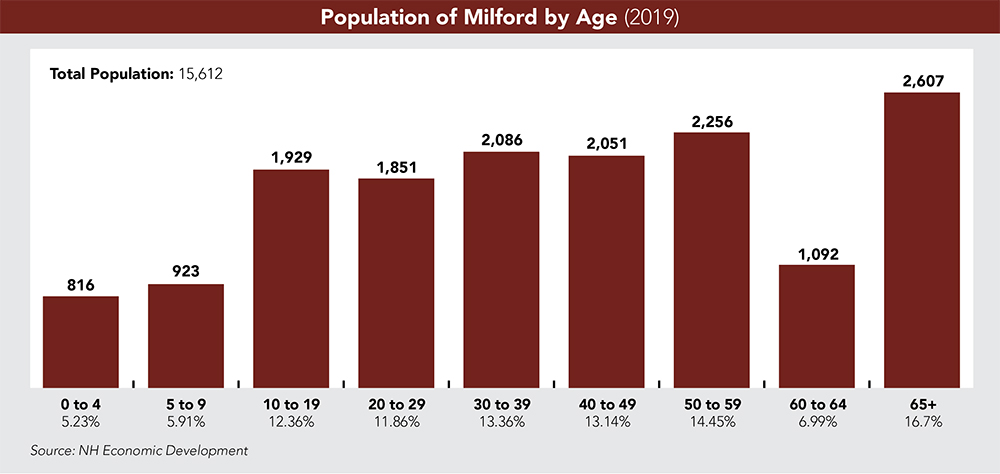

Demographic projections for Milford are working in Lehtonen’s favor. By the year 2024, more than 20% of Milford’s population will be over 65, which should only create more demand for his first-floor designs, especially since owners of existing ranches tend to hold on to their properties rather than downsize.

Demographic and Housing Challenges

Demographic and Housing Challenges

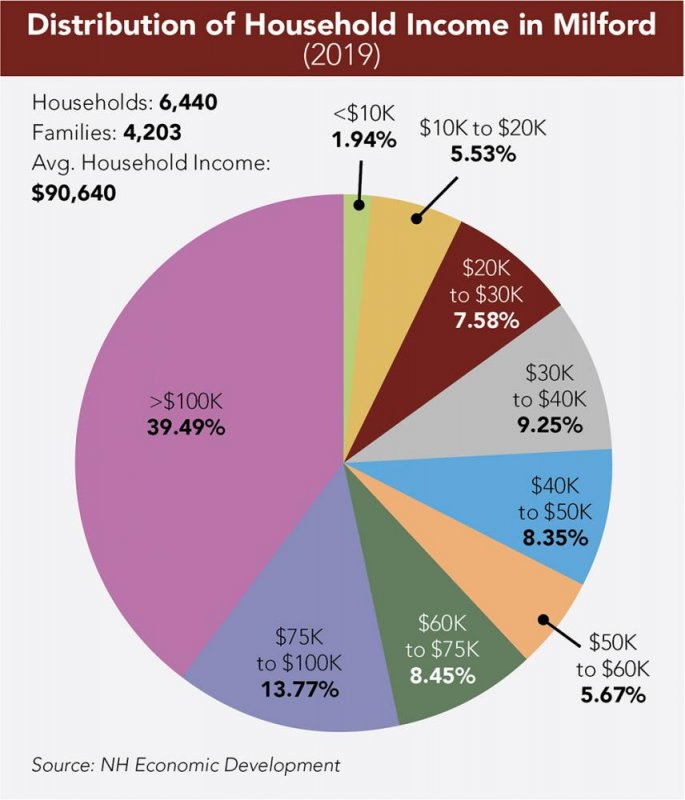

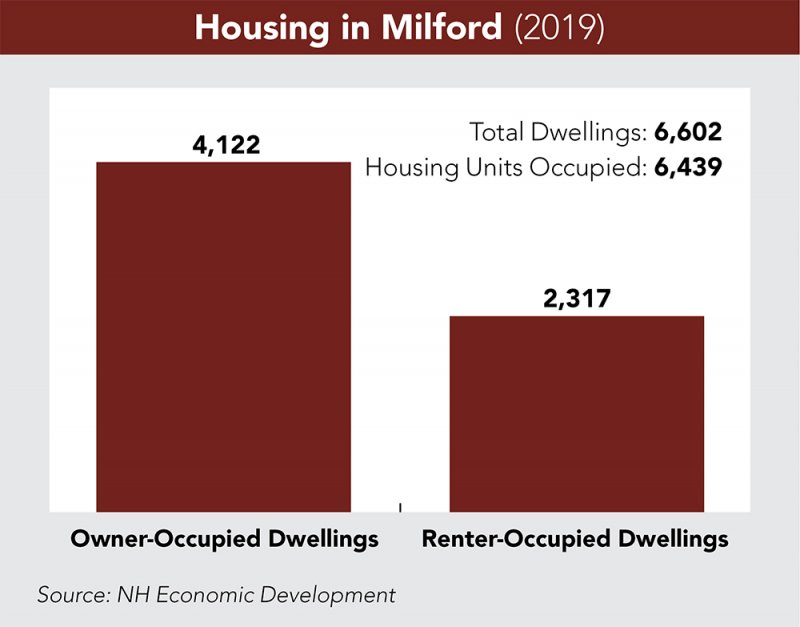

Neighborhoods like Autumn Oaks are not within reach for everyone. About half of Milford residents have annual household incomes under $75,000, and 15% earn below $30,000. Many choose to rent rather than own; Milford’s multi-family units comprise 40% of its housing stock. Only Manchester and Nashua have higher percentages of multi-family homes in Hillsborough County for towns and cities with more than 6,000 housing units, according to the most recent report from NH’s Office of Strategic Initiatives.

Increasingly, residents are turning to accessory dwelling units (ADUs), an apartment within a single family home, says Daley. During the past three years, Milford permitted 20 of them. Before 2017, the average request for an ADU was two or three per year.

An aging population and clusters of low-income households present challenges for rural municipalities like Milford, which are home to a higher proportion of older residents and see increased demands for services, affordable housing and access to public transportation.

“We’re looking at opportunities to improve the diversity of housing but not change the character of our community,” says Daley. “Balance is the key issue here.”

Offering more housing choices, improving public transportation and elevating the town’s commercial and industrial base top Daley’s priorities.

Offering more housing choices, improving public transportation and elevating the town’s commercial and industrial base top Daley’s priorities.

Ultimately, broadening the housing inventory will not help seniors who can no longer drive to doctor’s appointments, grocery stores and social events that are critical to avoiding isolation. Part of the problem is that Milford, which rests at the intersections of Routes 101, 13 and 101A, has limited public transportation.

Registered riders can request spots from Souhegan Valley Rides (SVR), a limited service that provides wheelchair-accessible transportation for non-emergency health care appointments and other essential activities in Amherst, Brookline, Hollis, Milford, Mont Vernon and Wilton. The SVR is Milford’s only transportation service. “Allowing more individuals to come and go within our community is going to be one of the challenges,” Daley says.

Many planners, including Daley, champion recently announced legislation, the Invest in American Railroads Act, which allows states to secure low-interest loans for rail projects, bringing hope that federal funding can pave the way for the heavily studied commuter rail line linking Nashua, Manchester and Concord to Boston.

Infrastructure Projects

In February, Mark Bender retired from his post as town administrator after five years and the completion of several long-term projects.

Following numerous delays, the town widened the well-travelled stretch of South Street between Union Square and a railroad right-of-way. The town installed utilities underground, enhanced sidewalks with granite curbing and beautified the street with lampposts that grace the views to Bicentennial Park and its statue commemorating the first female African American novelist, Harriet E. Wilson (pictured), who wrote, “Our Nig,” a slave narrative.

Following numerous delays, the town widened the well-travelled stretch of South Street between Union Square and a railroad right-of-way. The town installed utilities underground, enhanced sidewalks with granite curbing and beautified the street with lampposts that grace the views to Bicentennial Park and its statue commemorating the first female African American novelist, Harriet E. Wilson (pictured), who wrote, “Our Nig,” a slave narrative.

On the other end of South Street is the 19-acre Keyes Memorial Park with a swimming pool and baseball diamond. The park’s Elm Street driveway was once the Fletcher’s Paint Works Superfund site, a cleanup that began in the 1980s and stretched into recent years before safely removing the harmful chemicals found in the drinking water.

“We had a bonus to that project after it was finished,” says Bender. He is referring to an old rectangular stone-cutting shed that showcases the hammer and chisel methods quarry workers used in bygone eras. The shed sat on a plot of land slated for townhouse developments. After hearing about the historical significance of the shed, the landowners donated it to the town and moved it to the park. A team of construction, engineering and architectural volunteers rebuilt the shed into an angled band shell, wired with lights and sound to stage summer concerts in the park.

An old stone-cutting shed with historical significance, left, was moved to Keyes Memorial Park, and rebuilt into an angled band shell for summer concerts in the park, right. Courtesy photo.

Another project Bender checks off as finished is the cleanup of the 20-acre Osgood Pond. The town dredged the weed-choked body of water in 2017 and moved into phase two, dredging another six acres, making the pond habitable for fishing and boating.

Hitchiner Grows in Milford

When Milford-based Hitchiner Manufacturing Co. sought to grow its market by building aerospace super alloys and casting parts for gas turbine and jet engines, its leadership team considered constructing a plant further south.

Hitchiner Manufacturing’s new 95,000-square-foot facility. Courtesy of Hutter Construction.

Officials from Tennessee courted them with available buildings for half the cost per square foot than the facility Hitchiner eventually assembled in Milford. Tennessee also offered electric rates that were less than half NH’s rate and lower wages as well. “If we were to have made a decision based purely on financial incentives, we would have located somewhere else,” says CEO John Morison. “Every single aspect of the cost of installation was favorable for Tennessee.”

Neither the Governor’s office nor Milford’s town administrators were letting a potential $50 million investment slip by, particularly with a company deeply rooted in NH since 1946. (The manufacturer relocated from Manchester to Milford in 1951.)

The NH Business Finance Authority (BFA) huddled with town officials to craft a proposal for a public/private collaboration.

They offered to reduce the cost of Hitchiner’s project with a no-cost ground lease financed by a 10-year, interest-only bond, using a below-market interest rate. The terms promised to save Hitchiner an estimated $780,000 annually for a decade, allowing the manufacturer to put minimal up-front capital into a new building. Morison says state and town officials worked to expedite the permitting processes, particularly for air emissions and water. “That helped a lot,” he says.

The Milford location offered one other tangible benefit. When introducing a new technology to the product line, Morison says, “Proximity to the mother ship made it an easy choice to be here.”

By June, the new 95,000-square-foot facility will be up and running, and Morison says he anticipates adding 80 to 85 people to his 700 employees. The new building is on the site of a former Hitchiner plant that the company tore down in 1961.

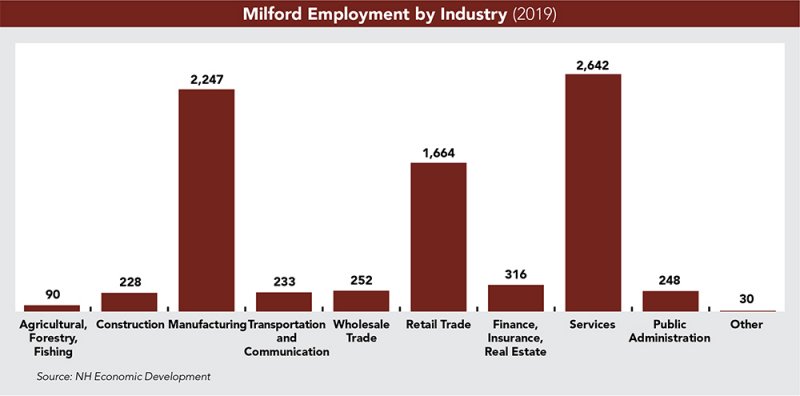

While Hitchiner is Milford’s largest employer, the town is also buoyed by several other companies. Milford has a long manufacturing legacy as its falls and dams along the Souhegan River powered grist and lumber mills, and later manufacturers of cotton, wool, furniture and shoes. Manufacturing continues to drive the economy. Alene Candles is a private-label candle and diffuser maker employing around 200 workers with extra hires around the holidays. Other major employers include Hendrix Aerial Cable Systems, a business unit of Marmon Utility; ultrasonic sensor manufacturer Airmar Technology; contract manufacturer Cirtronics; and machining manufacturer Datron Dynamics.

An employee working at Alene Candles. Courtesy photo.

An employee working at Alene Candles. Courtesy photo.

Rich Restaurant Scene

On any weekday afternoon, strangers hover around a long rectangular table inside the ethnically-inspired La Medina restaurant in the Milford Oval, dipping their slices of naan bread into the homemade hummus or savoring one of the many tagine or curry dishes.

The concept of communal seating is carried over from the previous proprietor, Jorge Arrunategui, who handed the reigns only six months ago to his friend, Rachel Barnard, who along with her mother, Marsha Rich, is betting on the burgeoning restaurant scene in Milford’s downtown.

Barnard, a former candy maker who has lived in Milford most of her 37 years, kept the colorful decor but is cooking specialty dishes to order rather than serving pre-packaged items out of a display case.

She joins a litany of mom-and-pop eateries in and around the Oval—Union Street Grill, Riverhouse Cafe, My Sister’s Kitchen, Papa Joe’s and Pasta Loft to name a few—that mainly cater to a breakfast and lunch clientele, although La Medina is also open for dinner.

Union Street Grill on the Milford Oval. Courtesy photo.

Cynthia Dokmo, a retired attorney and former state representative from Amherst, who is rehabbing two historic buildings in Milford, says she remembers a time in the early 90s when the Oval was lined with empty storefronts. “A lot of businesses came and went,” she says. But today, the town is bursting with energy and low vacancy rates, says Dokmo of Turtle Creek Properties.

She is restoring the 263-year old Col. Shepard House, which in previous incarnations was a Montessori school, a restaurant and an inn. The two-story building, which began as an 18th-century single family home, houses a small event space that Dokmo owns and Zingers, a comedy and music venue. She rents the upstairs offices to several entrepreneurs.

Col. Shepard House exterior and interior. Courtesy photos.

Dokmo is now turning her attention to the 100-year-old barn attached to the Col. Shepard House, which she hopes to convert into a larger event space. Rumors say its basement was a stop on the Underground Railroad where abolitionists and fugitive slaves found refuge. It was quite active in that area of town, she says, although oral legends rather than official documents attest to its existence.

“Milford has always been a very livable, vibrant community to me,” says Dokmo, who also invested in a former shoe store building at 1 Nashua St., which sat vacant for the last 12 years. She has a letter of intent from a chef who wants to open a new restaurant.

Another bright spot in the Milford mecca of dining establishments is Greenleaf, the brainchild of chef Chris Viaud and Keith Sarasin, founder of the Farmers Dinner, an organization hosting farm-to-table events across New England. Just under a year ago, Sarasin, along with Viaud, opened his first brick-and-mortar restaurant on Nashua Street in a renovated bank building dating back to 1865.

Keith Sarasin, and Chef Chris Viaud, right, owners of the restaurant Greenleaf. Center: A meal at the restaurant. Courtesy photos.

The pair sources ingredients from local vendors, including Lull, Holland and Trombly Farms in Milford. He scoped out many locations before settling on Milford, where he saw an opportunity for an upscale option among the fusion of casual cafes downtown.

As with any new restaurant or small business, Sarasin was tasked with finding staff in a tight labor market. Barnard of La Medina says that most qualified adults want jobs with benefits. “I don’t even have benefits,” she says. “I haven’t had health insurance for forever.” Six months into her launch, Barnard finally found a prep cook. “She has made my life so much easier.”

Sarasin is trying a novel approach: giving back 2% of food sales to the kitchen crew. “We feel it’s very important to help bridge that wage gap between the front of the house and the back of the house,” he says.

Another concern echoed by Milford Oval merchants is the scarcity of parking. Drivers park without meters and aren’t restricted by time, which means some leave their cars overnight.

In 2019, a community development survey found, not surprisingly, that employees were competing with their customers for spaces, especially during peak hours. Some business owners agreed to park within a safe walking distance from the Oval to free up spaces. Others are looking into alternatives, such as a valet service or an arrangement with the library’s parking lot.

“The challenge is convincing people to walk a little bit,” says Daley, and not park right in front of the store. Perception, not the lack of parking, is part of the problem.

Pumpkin Festival

Pumpkin Festival

One of the largest festivals in NH takes place in Milford. On Columbus Day weekend, for the past 30 years, around 45,000 people descend on the Milford Oval to listen to music, shop crafts, sample new foods and gawk at the spectacle of showcase pumpkins, which on occasion, breaks records. In 2018, Steve Geddes of Boscawen arrived with the heaviest pumpkin in North American history; it weighed 2,528 pounds (pictured).

Wade Campbell, who by day is a self-described “working class” steel worker, heads up the non-profit Granite Town Festivities Committee, which produces the three-day affair. And while he admits the festival has opponents who complain that a large-scale event triggers logistical headaches, he says the festival is beneficial to the town. For one thing, “It puts the town on the map,” he says. “It brings in people from all over. Even if they hang out for a few hours, they will probably hit the convenience store on their way out of town.”

Retail Draw

The Oval, with its coterie of antique stores, eateries, entertainment venues, boutique clothing and gift shops is becoming a destination shopping area.

Retail is thick in southern NH, and Milford is another Massachusetts border town that capitalizes on its tax-free advantage. Yet that’s not what brings consumers to Lorden Plaza, less than two miles down from the Oval.

According to Andy Chien, co-founder of the Seattle-based real estate investment firm, Bridge33 Capital, which owns 30 shopping centers and specializes in reviving tired malls, Lorden Plaza is a daily needs, neighborhood center.

Bridge33 purchased the Route 101A plaza in 2018 after a foreclosure. Chien says he wants to bring in tenants that offer services that can’t be easily replicated through e-commerce, such as food, haircuts, medical services, beer and wine.

Clothing and department stores no longer drive traffic to malls; supermarkets, fitness clubs and entertainment centers are the modern-day engines.

One of the busiest Shaw’s supermarkets in NH anchors Lorden Plaza, which will attract other retailers, Chien says. “We really like this shopping center in Milford because it’s a stable market with low unemployment and good employers,” he says.

Current Issue - April 2024

Current Issue - April 2024