The 26-year ban on federal student aid for incarcerated individuals that ended December 2020 creates a new audience for many colleges and universities that are competing for a shrinking pool of applicants. It also reignites a conversation about the types of educational opportunities that are available in prison and the potential for returning thousands of men and women to the workforce.

The New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE) released a report in February, “Higher Education Behind Bars, Expanding Post-Secondary Educational Programs in New England Prisons and Jails” that examines these key questions.

Some of the takeaways are: For each dollar spent on educational programming behind bars, taxpayers save $4 to $5 as providing higher education in prisons and jails decreases recidivism. It also improves the regional economy. The NEBHE report states that of the 45 New England prisons that publish educational data: 89% offer GED/HiSET or high school courses, 62% offer associate degree-granting courses, though only 17% offer bachelor’s degree-granting programs.

The authors say sharing promising practices that exist in the region can serve as models for creating post-secondary edu-cation programs in New England prisons. Massachusetts has the broadest range of programs run through several colleges and universities, while an employment-specific effort in Maine is cited as a “shining example” of a program using technology.

“Unlike the programs traditionally offered elsewhere, those in Maine allow for limited technology use among inmates. Without internet access and with sparse libraries, the information that inmates can typically access is incredibly limited,” the report states. “Maine, however, has introduced learning via tablets so that inmates stay connected with their courses.”

The NEBHE data shows there are no post-secondary programs in NH prisons, and according to the NH Department of Corrections (NH DOC), only those who have the funds or financial support to pay for college classes can earn a degree while incarcerated. Several U.S. colleges offer correspondence courses, which are permitted in NH prisons. It remains to be seen if the return of Pell eligibility may lead to an increase in college programs in Granite State prisons.

Back to Basics

Nationally, 56% of the general population has some college experience, while only 23% of incarcerated people do and a portion of those don’t even have a high school diploma.

While few individuals in NH state prisons are likely to emerge with a post-secondary degree in hand, there are opportunities to earn a high school equivalency certificate or a diploma in the prison-based high school as well as certificates in the trades and desirable business skills.

The Corrections Special School District that exists within the NH DOC includes Granite State High School and the Career & Technical Education Center.

In FY 2020, Granite State High School provided 248 intake assessments and 170 Tests of Adult Basic Education. In addition, 19 students passed the HiSET (high school equivalency exam) and 27 students were awarded their high school diploma.

High school equivalency programs are also available in the county jails, says Sarah Wheeler, administrator of the Adult Education Division of the NH Department of Education (NH DOE).

Some county jails contract with local adult education centers, including Strafford County, which works with the Dover Adult Learning Center (DALC). “For many years, [DALC] has provided classes and GED/HiSET testing at the jail using their own instructors,” she says. “Rockingham County contracted with Exeter Adult Ed but has hired a staff adult educator who is taking on the teaching tasks and setting up their own HiSET testing center. In Carroll County, Governor Wentworth Regional School District runs a program with volunteer tutors and relies on Strafford County for the testing.”

Wheeler says most facilities don’t have the technology to support online education and testing. But some counties are making strides. Rockingham County has tablets designed for use in correctional facilities that limit access and block certain apps. Belknap is looking into similar tools.

Because the average stay at a county jail is a few weeks or less, it is difficult to engage students when they are there for such a short time or to complete the preparation and testing for high school equivalency, Wheeler says.

The Community Corrections model, which provides a framework for serving a sentence outside of a facility, has reduced jail populations and sentence lengths; as a result, there are fewer candidates.

“We used to have about 50 graduates and now it’s closer to 25 to 30,” says Deanna Strand, DALC executive director.

Wheeler says DOE has a contract with the Department of Corrections to provide adult education and literacy at five facilities in the state prison system. The contracts went into place in July 2020, but all the facilities were under lockdown.

Trades and Certification

The DOC Career & Technical Education Center in Concord offers eight career and technical education training programs at the state’s three correctional facilities. Certifications can be earned in hospitality and tourism, IT, and building trades, among others. The center is also offering training in advanced Microsoft applications that will lead to a Microsoft certification.

DOC had been running its own adult education programs for a couple of years along with preparation to earn a commercial driver’s license (CDL), Wheeler says. There is high demand for CDL drivers and they can earn around $50,000 per year. “They have a simulator, and upon release, individuals are connected to a testing facility,” says Wheeler. “It gives these students options to plan for their future.”

The NH Department of Transportation also works with DOC to allow individuals to job shadow highway maintainers.

NHTI-Concord’s Community College runs a pre-apprenticeship program partnering with the DOC and ApprenticeshipNH, through which NHTI provides short-term, technical education training programming in CNC machining, says Beth Doiron, director of college access and DOE programs and initiatives for the Community College System of NH.

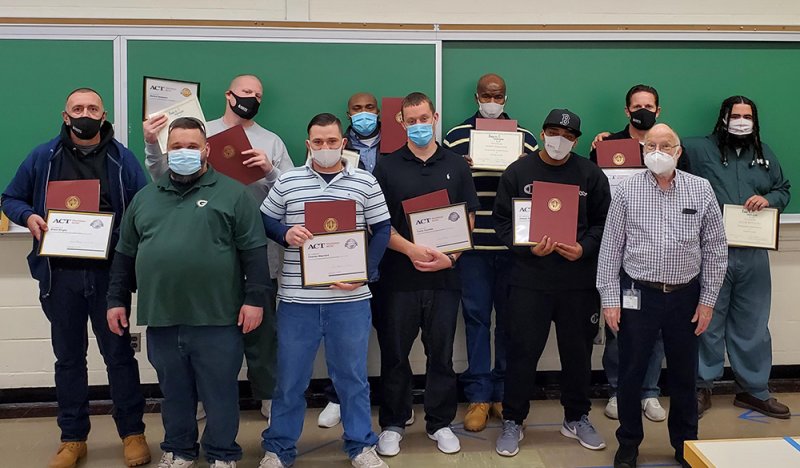

NHTI’s pre-apprenticeship program participants and instructors. Courtesy photo.

“Participants gain skills necessary for entry-level employment that may be applied to the required related instruction hours of a Registered Apprenticeship,” she says.

As a pre-requisite to the machining program, students must take a three-week WorkReadyNH training focused on the soft skills required for employment, she adds.

Workforce Opportunity

NH Employment Security (NHES) developed a reentry program in cooperation with the DOC to provide services to those currently in federal, state or county correctional facilities who are soon to be released. The majority of the participants will also be eligible for the WorkNowNH Program, developed in partnership with DOE to refer inmates to an adult education center to learn digital literacy and other employment skills.

Those leaving prison are co-enrolled in the Reentry Program and WorkNowNH Program and can select whichever benefit is greater to help them reach their goals.

Upon enrollment in WorkNowNH, NHES does a series of one-on-one case management meetings to determine a person’s vocational interest, then an employment counselor helps create an individual employment plan.

Richard Lavers, deputy commissioner of NHES, says the program will pay up to $5,000 per year per individual and will pay for a second year if the person wants to continue. The program also pays for books, fees and a portion of transportation costs.

NHES hosts workshops to build awareness of the program prior to release. “Hopefully, it leads to higher rates of participation among folks that are re-entering after having been in a correctional facility. We can provide solid assistance [for] getting back into the workforce. The more we can do to act quickly, the less likely they will end up back in a correctional facility,” says Lavers.

An Opportunity for Colleges

With people in correctional facilities now able to access the Second Chance Pell Grants, there’s opportunity for colleges to access a new pool of students. Taking the lead in tapping that market will likely be Southern NH University (SNHU).

Project AIM, a program SNHU hopes to bring to NH correctional facilities in 2022, began with a chance meeting. “It started as a class project,” says Chris Matthews, associate professor of business management at SNHU, “I’m always looking for ways to take my students outside the class. An opportunity presented itself in a casual conversation with a stranger seated nearby at a theater performance.”

Chris Matthews, associate professor of business management at SNHU. Courtesy photo.

As Matthews explains, that conversation led to a project for his students “to see and better understand the impact of incarceration on business, government and society.” Four times during the semester they would spend time with 26 incarcerated men at a facility in Connecticut.

“Over the course of the two years that we were going down there, the students were asking how we could create a pathway for these men to get a degree,” says Matthews. “I told them, ‘you’re business students, write a business plan’ and they did.”

Matthews presented the plan to SNHU President Paul Leblanc, who agreed to give it a shot. “We officially launched Project AIM in the fall of 2019 with the 26 incarcerated men in Connecticut,” says Matthews. “The correctional officers at the facility noticed an immediate change in the guys’ behavior, and we now have a waiting list of 60 men.”

AIM, which stands for Achieving Independence and Mobility, allows learners to earn a series of 10 badges, which introduce them to the college experience, including “What does it mean to study? How do you complete your assignments?”

The plan was to complete the 10 badges in 12 months through twice-weekly, 3-hour sessions, but the pandemic slowed them down. “When COVID hit we had to go back to old school correspondence learning,” says Matthews. “We would drop off and pick up the materials. It did take a lot longer with pen and paper, but it was well worth it and we felt the learners were extremely committed.”

Once students complete the program, they are automatically admitted to SNHU and assigned an academic advisor. “Even if you decide not to become a SNHU student, those badges still bring value to the student and community,” Matthews says.

Seeing the potential, the Connecticut correctional officers asked for a pathway for themselves. “We created it and started the staff cohort in fall of 2020,” says Matthews. “The correctional officers, with better access to the internet, were able to complete the program despite the pandemic, and begin their actual SNHU journey this fall 2021.”

Matthews says he hopes to have a program ready for NH in fall 2022. Right now, he is convening stakeholders and identifying key community partners. “Our goal is not just education, but to make sure that once released, the individuals can find housing and get a job,” he says.

Per the NEBHE report, providing higher education is beneficial to incarcerated students, their incarcerated peers and to prison culture in general, and the positive changes in Connecticut are an example to build on.

“The facility in Connecticut has one of the oldest infrastructures in the state, with limited access in general. But because officials were able to see the change in the men and how this educational pathway was directly impacting the incarcerated individuals, they began to invest,” says Matthews. “It has been a crazy journey, but in a good way, as we have seen some unintended consequences of providing this education.”

Current Issue - April 2024

Current Issue - April 2024