Therese Willkomm created some assistive technology solutions to help Kevin, an employee at Home Depot, communicate with customers. Courtesy photo.

People with disabilities are the largest minority on the planet, according to Colorado comedian Josh Blue, who has cerebral palsy.

“Because they pile us all together. If you’re blind, join the pile. If you’re deaf, help the blind guy find the pile. If you’ve got one leg, hop on the pile.—Ok, I’ll stop,” he says, feigning shame over the jokes during a live performance recorded in 2016. Furthermore, you never know who’s going to join the pile.

This is one reason, among many, for employers to learn more about accommodations and assistive technologies that make it possible for qualified workers with disabilities to work or continue working. In a state with an aging workforce and a tight job market, excluding any group, let alone one that may be the world’s largest, risks leaving a company at a competitive disadvantage.

Of course, it’s also the law. State and federal law prohibit employers from discriminating in hiring solely because of a disability.

The federal law applies to companies with 15 or more employees. But NH law prohibits discrimination for most companies with six or more employees—including temporary and part-time workers. The law also requires employers to provide “reasonable accommodation” to enable a qualified worker to do the job unless that causes “undue hardship.”

“The kinds of things that you look at in order to determine if it’s an undue hardship or not include things like cost, impact on the business, impact on other employees. And something that might be reasonable in a large company may not be reasonable in a small company,” says Charla Bizios Stevens, a lawyer who leads the employment practice group at McLane Middleton in Concord. “It’s very subjective and fact-specific.”

Tapping Resources

That kind of subjectivity can make employers nervous, but there are resources out there to address concerns employers might have about the law and whether someone with a disability can do a job safely and meet professional standards.

“One thing would be to reach out to agencies like ours to have a conversation about what those fears are,” says Anne Hirsh, co-director of the Job Accommodation Network or JAN, a free service of the U.S. Department of Labor’s Office of Disability Employment Policy.

Employers can contact experts there by phone, email or even internet chat to learn more about what accommodations might be possible in any given situation. “We’re confidential; they don’t have to give us their names,” Hirsh says.

Employers are encouraged to be specific about their workplace and any given disability. “And with that information, we’ll try to give as many ideas as we can to allow that employer to make an informed decision about what would be most effective for their work environment.”

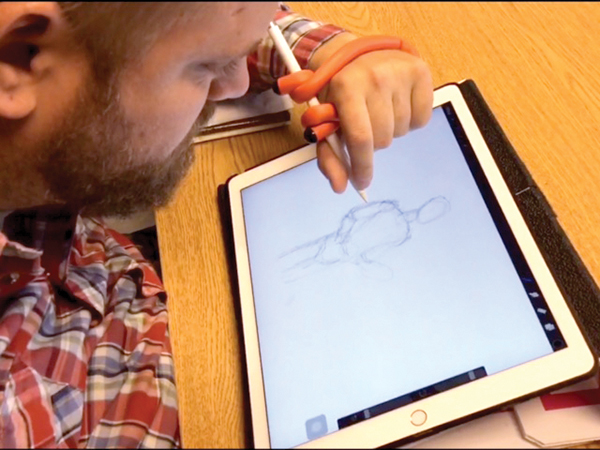

A client at the UNH Institute on Disability uses a modified pencil grip. Courtesy photo.

The NH Vocational Rehabilitation program serves as a resource to businesses in NH as well as helping individuals with disabilities find work. “Vocational Rehabilitation and JAN: we are not the disability police. We want to be here as a total resource.

We’re not here to make sure you’re in compliance. We’re here to help you,” says Lisa Hinson-Hatz, state director of the NH Vocational Rehabilitation program under the Department of Education.

Another resource is the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which has extensive information on its website about policies and procedures addressing reasonable accommodations.

Safety and Cost Concerns

Not surprisingly, one of the leading concerns about hiring or retaining a worker who needs an accommodation is cost. So it may come as a surprise that the majority of accommodations cost little or nothing. Often an accommodation is as simple as a scheduling adjustment. There are also a number of new smartphone applications that can assist workers with disabilities, such as an app that converts speech to text for the deaf or hard of hearing.

“Sometimes they actually have the technology onsite, it’s just turning it on—using the narrator product in Office products ... or turning on the screen magnification,” for someone who’s visually impaired, Hirsh says.

For workers with a developmental disability, sometimes the accommodation is extra time in training; for a memory impairment, a laminated checklist, says Hinson-Hatz.

A second common concern is safety, especially in an industrial setting when a worker is deaf or hard of hearing, Hirsh says.

Safety adaptations can include flashing lights added to a fire alarm system or giving the worker devices that vibrate instead of making sound to raise an alert.

According to JAN’s survey of more than 700 employers who’d provided accommodations, the majority (59 percent) cost nothing, and the rest averaged a one-time cost of $500. When there are higher costs for assistive technology, federal tax breaks, including one that can pay for as much as 50 percent of the cost, can help. Vocational Rehabilitation can also help workers acquire technology they need to succeed.

In addition, Hinson-Hatz says her agency can help employees and employers explore options before anyone commits to paying for something expensive. “We do an assistive technology evaluation to determine what is going to be the best solution,” she says, adding once a potential solution is identified, many technology providers will allow a worker to test it free of charge for several months. “We don’t want to use something that’s not going to work.”

Therese Willkomm is known in NH as “the MacGyver of assistive technologies.” In her role as director of the Assistive Technology in NH program at the University of NH’s Institute on Disability, she is yet another resource.

Willkomm calls her work “problem solving,” and it’s not necessarily high tech. Employers and employees may be surprised at what they find just by using Google or Pinterest for ideas in assistive technology. “There’s a lot of options. Cost doesn’t have to be something that prevents an employee or an employer from making the accommodation,” she says.

Addressing Productivity Concerns

Willkomm says besides cost, employers worry about productivity. “What we’re finding is that many employees with disabilities who are hired and are then let go, are often let go because they can’t meet the industrial standards,” she says.

For job applicants with disabilities, she advises they learn to use any assistive technology in advance, so they can show a prospective employer that they can meet professional demands, similar to the way office workers used to take typing tests.

The law prohibits an employer from asking about a disability during hiring. Typically, this means an employer who wants to test any applicant’s proficiency will have to do that for every applicant, disabled or otherwise, creating a standard pre-employment test, according to Bizios Stevens.

But Willkomm says there are other ways to address concerns in an interview. “There’s nothing wrong with an employer saying: we are expecting that all of our employees are going to be able to do [a task]. Can you perform that, and if so, how would you do that? Show me,” she says.

Once a worker is hired, if accommodations are needed, talking about them with that person will be critical. This also applies to any existing employee who develops a disability. “You really can’t have that discussion without the individual’s involvement.

More than likely, this person has dealt with this issue somewhere else in their life, so they’re going to come to you with the best information about how they could be accommodated,” Hirsh says.

If a new employee is getting support from an agency that serves people with disabilities, like Vocational Rehabilitation, that agency also can serve as a post-employment resource, Hinson-Hatz says.

While the Americans with Disabilities Act requires medical information be kept confidential, many people with obvious disabilities or accommodations prefer their colleagues and supervisors know something about how best to communicate with them, or how to deal with something like a sign language interpreter or a guide dog in their midst. In those cases, some workplace education around inclusion makes sense for colleagues and particularly for managers.

Better Workplaces

The good news is that employers who make accommodations to create a more inclusive workforce are generally happy with the results, according to the survey and resulting report for JAN, “Workplace Accommodations: Low Cost, High Impact.”

Direct benefits included retaining valued employees and improving employee productivity. But indirect benefits were also reported, including improved interactions with co-workers and increased company morale.

That fits with Hinson-Hatz’s observations as her agency helps to place workers with disabilities in jobs. Inclusive workplaces are often happier workplaces, where employees are encouraged to support one another, she says, adding there is no reason to be afraid of hiring someone with a disability. “Listen, you have fear of the unknown with anyone you hire, right?”

Like any employee, workers with disabilities, given the right support, can be successful and productive in the workplace, Bizios Stevens says. “If somebody has the training, the skills, the education to perform the job, then a disability is usually not an impediment to having that person be a successful employee.”