The shortage of health care workers is unlike anything Steve Ahnen has seen in his 15 years as president of the NH Hospital Association. “This is certainly one of the most challenging environments for [the] health care workforce that I’ve ever seen in my career,” he says. “Whenever I talk to people in the industry, I hear the top three concerns over and over—workforce, workforce, workforce.”

The alarm bells have been sounding loudly and frequently. In November, the NH Health Care Workforce Coalition wrote to Gov. Chris Sununu and other state leaders warning that, “The COVID-19 pandemic put serious strains on an already challenged health care workforce in the Granite State.”

“Across the healthcare sector, the difficulty to recruit, retain, and fully staff facilities and programs is seriously impinging on patients’ access to care and deepening financial stress for our state’s health care providers.”

The coalition of 50 different organizations representing a broad spectrum of health care providers laid out a detailed plan on how the state should invest millions of dollars in federal COVID recovery funds to address the problem, including student loan repayment programs, housing subsidies and expansion of state-funded recruitment efforts.

In March, the NH Endowment for Health released a state plan with strategies to address the crisis, “Giving Care: A Strategic Plan to Expand and Support New Hampshire’s Health Care Workforce.”

“The healthcare sector is the fastest growing industry in New Hampshire and while labor shortages are not unique to this sector, the workforce shortages are very acute,” the Endowment states in the plan’s executive summary. “Right now, health care is the sector with the most unfilled positions in New Hampshire. While predating the pandemic, these workforce shortages became a crisis with the incredible increase in demand for patient care across the healthcare system due to COVID-19.”

Many Efforts Underway

Initiatives promoted by the Workforce Coalition and the Endowment for Health reflect and expand upon many of the efforts already underway among healthcare providers and the educational institutions they partner with to address workforce needs.

These include expansion of educational facilities and programs to accommodate more students; easing the requirements for on-the-job training and licensure; faster turnaround on background checks; and enhanced benefits like day care, tuition reimbursement, housing assistance and student loan payoff.

“I don’t think there’s a part of the state where this isn’t a primary issue,” says Ahnen. “It affects folks across New Hampshire. Certainly, rural communities have always faced workforce challenges in health care, but that doesn’t mean southern and seacoast and other larger population centers aren’t facing the same challenge.”

One positive trend is an increasing number of high school graduates seeking secondary education and certification in a healthcare discipline. Universities, colleges and community colleges in NH have responded aggressively with construction of new health science buildings and simulation labs, additional faculty and new programs.

Rivier University in Nashua opened a 10,000-square-foot nursing simulation and clinical education center in March, coming on the heels of a 36,000-square-foot science and innovation center that opened in 2020.

Rivier University students and their professor working in the nursing simulation and clinical education center. (Courtesy photo)

In 2017, Rivier had 262 nursing students in baccalaureate programs, compared to 435 graduating this spring, according to University President Sister Paula Marie Buley. The associate degree nursing program had 87 graduates in 2017 compared to 262 this year.

Clinical Experience is Key

The capacity of the schools to turn out new practitioners, however, is somewhat constrained by the requirement these degrees impose for experience in a clinical setting.

“If you’re studying to be a nurse practitioner, you need 500 hours under a registered clinician,” says Sister Buley. “The current clinicians are so overburdened and stressed that it’s very hard for them to take on a student. So, we’re fortunate to have the generosity of the clinicians we are working with, but there is a bit of a ceiling to ensure we can add students to a clinical setting.”

The University of NH opened a $9 million Health Sciences Simulation Center in November, with more than 20,000-square-feet of offices, classrooms, labs and fully equipped simulation rooms that mimic hospitals, clinics and primary care situations.

Prior to construction of the new facility, UNH had been graduating around 60 student nurses annually, says Gene Harkless, chair of the Nursing Department. “To get that up to 96 to 100 graduates every year, we had to have a new physical space for clinical education,” she says. “With the opening of the new center this fall, the sophomore class was at 90.”

The community college system has benefitted from state funding to support its licensed practical nurse program at locations throughout the state. “We expect by next year we will be in position to enroll about 100 LPN candidates each year,” says Mark Rubinstein, chancellor of the Community College System of NH. “My last look at statewide demand was 182 LPNs required each year. So, the ability to meet half of that demand next year is good progress for a program that didn’t exist three years ago.”

Despite these initiatives and many others at other institutions, the supply of healthcare workers is still falling far short of demand. “The staffing crunch is the worst I’ve seen in four years here at Catholic Medical Center,” says Jennifer Cassin, vice president and chief nursing officer at CMC in Manchester. “Prior to that, I was working in Upstate New York, and it’s definitely the worst I’ve seen in my career. I don’t think it’s ever been this bad, honestly.”

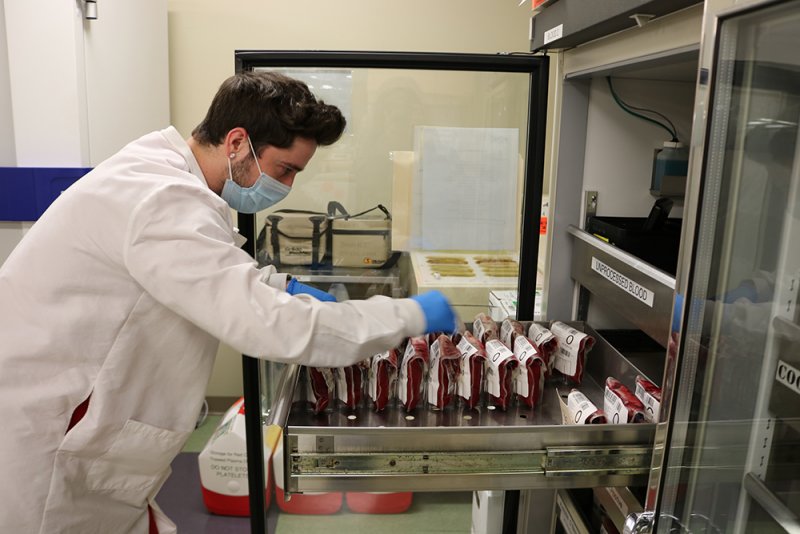

Scott Morin, Catholic Medical Center medical technologist, working in the lab. (Courtesy photo)

You Have to Woo Them

During the recession of 2008-09 and continuing into the middle part of the last decade, professionals tended to stay put, given the shrinkage in the job market and 401K balances. But those days of relatively comfortable staffing levels are a distant memory, says Merryll Rosenfeld, vice president of human resources at CMC.

When it comes to hiring now, she says, “You have to woo them. When that application comes in the door, you need to call right away because someone else is scooping them up if you’re not.”

That wooing at Elliot Health System in Manchester includes benefits such as the Elliot Child Care Center, located on the Elliot Hospital campus, serving infants and toddlers through kindergarten. The program is available to employees.

The Elliot Child Care Center. (Courtesy photo)

“About three years ago, we ran focus groups with nurses, and we said if we want to make this a great place to work, what do we need, and if we’re looking at career development opportunities, what aspects are you looking for?” says Rebecca Marden, director of workforce development at Elliot Health System.

“Day care came up, but the number-one thing was a student loan forgiveness program,” she says. The Elliot program is based on longevity, starting at $200 a month and increasing to $400 a month for a maximum of $20,000. That’s in addition to sign-on bonuses, tuition reimbursement and competitive wages.

The result of all these incentives and a multi-pronged recruitment program is that the Elliot hired more than 200 nurses in the last 12 months, but 223 openings remain. That is an indication of just how tough the competition is for these workers.

Can the Tide Turn?

If COVID becomes endemic instead of pandemic, most of the health care professionals interviewed for this article agree that there are efforts in the works and trends under way that will address the shortage over time and bring staffing levels closer to the market demand for services.

“National studies say we are going to see this issue up to 2030, and maybe even beyond,” says Cassin at CMC. But she’s convinced that efforts now under way are starting to bear fruit. “It’s about hospitals and colleges collaborating and strategizing together to meet demand. Colleges do one part; hospitals have to support that with clinical hours that students need at the bedside.”

Those partnerships have expanded across the state, involving multiple health care systems and post-secondary education institutions. And hospitals are aggressively recruiting out-of-state talent by promoting NH’s quality of life. Whether all that proves sufficient, only time will tell.

“I’m really optimistic,” says Harkless at UNH. “I’m 68 now; I love nursing; I love what I do, and I want the next generation to love it as much as I do. I want the best nurses taking care of me at end of life or when I need acute services. I want to be cared for at home; I want direct access to care. I want to make sure I’m not put on hold or put into a queue to see a doctor three weeks later. I want a nurse to be there to take care of me and help my family understand my needs, and I think we can get there.”

Current Issue - April 2024

Current Issue - April 2024