"I noticed something is different with you,” is not a typical way to initiate a dialogue with a co-worker. But when a colleague is unexpectedly showing up late, missing days, or exhibiting poor hygiene, an opener like this may help unravel the circumstances. It may also help save a life.

Todd Donovan is a 48-year-old firefighter and paramedic with the Derry Fire Department who struggled with depression and suicidal thoughts for years before receiving treatment. Now a public speaker with the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), he encourages the difficult conversations his peers in the department never had with him.

From the time he was a child until he was 44, Donovan thought about ending his life. He says he was hospitalized six times. Time and again, he told himself his suicidal tendencies would go away if only he became more religious, got married, landed a good job, went to college, or had a family.

“There was always something I was trying to achieve to make that pain go away,” says Donovan. “But it never would. It was always there.” About four years ago, he found a treatment that worked, transcranial magnetic stimulation, a non-invasive method of brain stimulation that targets nerve cells in the area of the brain thought to control mood.

“It worked so dramatically I realized it [the depression] wasn’t my fault,” he says.

NH’s High Suicide Rate

Amidst an alarming report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention on the escalating rates of deaths by suicide, Donovan is now an advocate for addressing suicide as a national health crisis and alerting the public of the risk factors and warning signs of suicidal behavior.

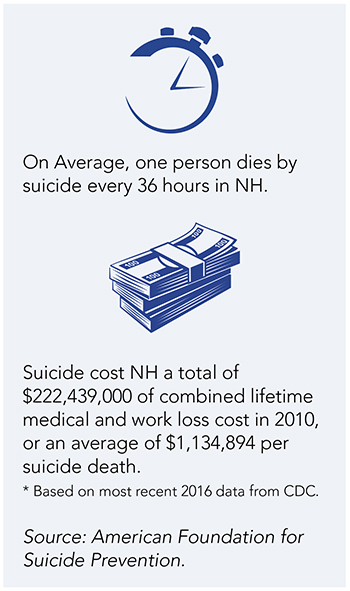

The CDC reports an uptick in suicides between 1999 and 2016 in nearly every state with half of the states showing at least a 30 percent increase. New Hampshire’s climb was 50 percent, ranking third among states for the highest increase in suicide deaths. On average, there are 123 suicides per day nationwide. Half involve the use of firearms.

Nationally, white, non-Hispanic middle-aged men comprise the majority of suicides.

The CDC report also notes that among people who died by suicide, more than half had no known mental illness. Some experts speculate that the toll of untreated depression is at its peak when individuals are besieged with caring for aging parents, financing their children’s education, preparing for retirement, dealing with health issues, leaving a marriage or looking for a job.

Research from the Carsey School of Public Policy at the University of NH is equally troubling. Nationwide, the mortality rate from deaths involving drugs, alcohol and suicide rose 52 percent from 2000 to 2014. In contrast, deaths from diabetes, heart disease, most cancers, and car accidents, are on the decline. For young white men, drugs, alcohol, and suicide eclipse any other cause of death. Princeton researchers Anne Case and Angus Deaton have been studying this spike in suicides and drug and alcohol overdoses among middle-age white men. In scenarios like Donovan’s, a genetic-based depression lies at the root of the problem.

Research from the Carsey School of Public Policy at the University of NH is equally troubling. Nationwide, the mortality rate from deaths involving drugs, alcohol and suicide rose 52 percent from 2000 to 2014. In contrast, deaths from diabetes, heart disease, most cancers, and car accidents, are on the decline. For young white men, drugs, alcohol, and suicide eclipse any other cause of death. Princeton researchers Anne Case and Angus Deaton have been studying this spike in suicides and drug and alcohol overdoses among middle-age white men. In scenarios like Donovan’s, a genetic-based depression lies at the root of the problem.

Yet Case and Deaton write in a paper they published for the Brookings Institute in the spring of 2017 that other factors are at play. They suggest that what they call “deaths of despair” are a result of “deterioration in economic and social wellbeing.”

Case and Deaton theorize that economic hardships, the dearth of community supports and lack of social interactions are triggering a decades-long trend of shorter life expectancies among white males, especially those without a college degree.

The Princeton economists also point out that European countries are not witnessing the same decline in mortality rates among middle-aged white men. “The Europeans are not killing themselves the way Americans are,” says Case in a video interview with the Wall Street Journal. “They’ve lost jobs [too.]”

Why the big difference between the two cultures? The researchers point to the breakdown of marriage, a loss of connection to faith communities and the lack of a social safety net that Europe’s high taxes provide.

The reasons behind the surge in suicides are multi-layered and complex. The recent celebrity deaths of journalist and chef Anthony Bourdain and fashion designer Kate Spade symbolize how easily those who seemingly are at the top of their game can mask their internal demons. The losses of these well-known figures are not only startling, they underscore that no one—including those with fame and wealth—is impervious to feeling alone and helpless.

Suicide Prevention

Ken Norton who directs NAMI-NH, says there’s reason for hope. He says we need to look at the CDC’s numbers from a historical context: a national strategy was developed in 2001 with funding to implement it made available in 2005.

“We brought down heart attacks by publishing the warning signs,” says Norton, who claims the same can be done for suicide prevention as long as the country’s leaders attack it as a public health crisis.

According to the World Health Organization, one in four people suffer a mental or neurological disorder during their lifetime. They lose a parent, end a relationship, or scramble to pay the bills. Their struggles, or those of their family members, cause them to miss work and not perform at their best.

Jennifer Schirmer is a licensed mental health counselor, and at the time of the interview was an employee with the NH Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and is now a contractor with them. She helps organizations respond to disasters and says she assists when DHHS receives calls from companies where a death by suicide has occurred at work or at home.

Co-workers share a relationship with the deceased person in ways no one else has, says Schirmer, and in addition to expressing shock, they find themselves wondering if there’s anything they could have done. It’s a grief that is layered with unanswered questions and a replay of final moments.

“When you think of any business” says Schirmer, “it’s a collection of people who work together nearly every day. They’re a natural community.” That community can take on the role of an extended family, says Amanda Grappone Osmer, the fourth-generation steward of Grappone Automotive in Bow. Osmer relies on Easter Seals to train front line managers on how addiction and mental illness affect families and how to respond by providing a safe and approachable place to work. The company also has an employee assistance program to help employees with mental health issues. “We can’t fix every problem,” she adds. “But we can direct them to wonderful resources.”

Fostering that spirit of support is also a priority at W.S. Badger in Gilsum, which manufactures natural skin products and employs around 90 people. Emily Hall Warren, the director of administration, says the company invests in training to create a supportive environment. The company is also crafting a policy to support those suffering from addiction and mental illness in the same way it would anyone with a physical illness, such as cancer.

Warren is careful to point out that the company’s emphasis on mental health is not a symptom of an unstable workforce. “We’re in a state that has the third largest problem with addiction,” she says. “If you turn a blind eye to it, you’re ignoring a huge part of what’s going on.”

Norton says that some industries carry a higher risk for suicides than others: for example, farmers, fishermen and lumberjacks, according to a CDC study. In general, people who perform manual labor or work alone are also at risk. Another predictor is access to lethal weapons. In law enforcement, more police officers die by suicide than are killed in the line of duty, says retired Major Russell Conte of the NH State Police, who now serves as the department’s part-time mental health and wellness coordinator. “That’s a staggering statistic,” he says.

Among the NH State Police, Conte says he hasn’t heard of any incidences of suicide in the last 10 years. He credits that, in part, to the peer counseling program he helped to develop that trains some troopers to serve as confidantes for first responders dealing with traumatic crises and the psychological repercussions that occur from them. “We’re going to help them [the troopers] through it,” he says, without fear of stigma or discipline, and long before the behavior escalates to the level where troopers can’t perform their jobs.

Schirmer says she sees many organizations doing just that. They may use modules like the eight-hour Mental Health First Aid course (mentalhealthfirstaid.org/at-work/); CALM: Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (sprc.org/resources-programs/calm-counseling-access-lethal-means) or ASIST: Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (livingworks.net/programs/asist/). Businesses can also call local mental health community centers or hospitals to find a course or trainer that fits their business needs.

Recognize the Warning Signs for Suicide

Take action if you see any of the following warning signs:

• Talking about or threatening to hurt or kill oneself

• Seeking firearms, drugs, or other lethal means for killing oneself

• Talking or writing about death, dying or suicide

• Direct statements or less direct statements of suicidal intent (“I’m just going to end it all” or “Everything would be easier if I wasn’t around.”)

• Feeling hopeless

• Feeling rage or uncontrollable anger or seeking revenge

• Feeling trapped, like there’s no way out

• Dramatic mood changes

• Seeing no reason for living or having no sense of purpose in life

• Acting reckless or engaging in risky activities

• Increasing alcohol or drug use

• Withdrawing from friends, family and society

• Feeling anxious or agitated

• Being unable to sleep, or sleeping all the time

Source: NAMI New Hampshire

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, call the U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255). You can also chat online with someone at suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

Current Issue - April 2024

Current Issue - April 2024