Alice Peck Day Memorial Hospital pediatrician Doug Williamson tends to a patient. Courtesy photo.

Pediatrician Doug Williamson at Alice Peck Day (APD) Memorial Hospital in Lebanon remembers the day, 21 years ago, when he received the hospital’s job offer. Then-president Bob Mesropian shook his hand and told him he’d work out the contract later.

Williamson was the only pediatrician at the hospital when he was hired and one of only six providers. After he retires this summer, the staff will include three pediatricians and 16 providers. “APD has always been an organization with a personal touch and a focus on individuals and families,” says Williamson, noting the health care organization’s philosophy: “If you deliver high-quality care, the rest will follow.”

But delivering on that is now harder for rural hospitals. Alice Peck Day, with 19 inpatient beds, is only four miles from Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (DHMC), NH’s largest hospital with almost 400 beds.

Launched in 1932, Alice Peck Day retains the small-town vibe that Williamson found so engaging as a recent graduate of Dartmouth Medical School (now Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth). Much has changed, though. For one thing, that personal, capital-intensive care is getting harder for small rural hospitals to pay for as technological and regulatory demands escalate and Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements shrink.

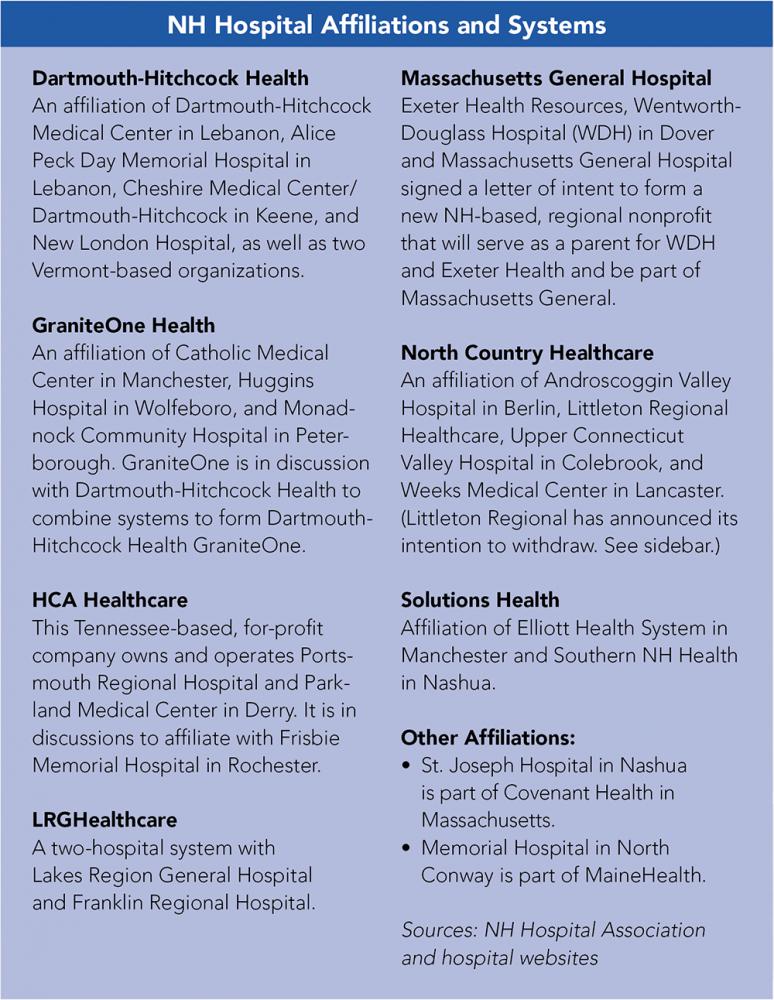

In 2016, Alice Peck Day formally affiliated with Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health, joining Cheshire Medical Center/Dartmouth-Hitchcock in Keene, New London Hospital , Mt. Ascutney Hospital in Windsor, Vt., and Visiting Nurse and Hospice for Vermont and NH , as members (but retaining their own identities).

Susan Mooney, CEO of Alice Peck Day, says that by affiliating, the hospital achieved economies of scale, integrated back office functions, and improved electronic health records. “It was the right thing to do for our community,” she says.

Rural Hospitals Stronger in NH

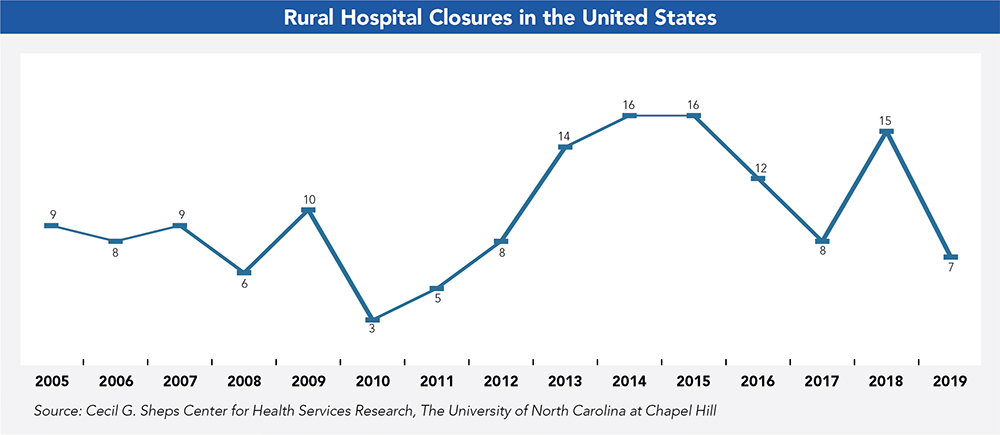

Alia Hayes, NH Flex Program coordinator with the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, says NH’s hospitals are in better shape compared to the national landscape. The fate of rural hospitals in the South, for example, remains particularly tenuous. Since 2005, more than 140 rural hospitals have closed, and this trend is on the uptick, according to George Pink of the North Carolina Rural Health Research and Policy Analysis Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The fiscal health of a hospital is such an integral part of its community that when a region’s sole hospital closes, it reduces per-capita income by 4 percent and increases unemployment by 1.6 percent, per data from Health

Services Research.

Often a rural hospital is the one place in town that keeps its doors open around the clock. Its personal connections with its patients, local vendors, schools and public health departments bolster the vitality of the surrounding neighborhoods.

Financial distress is the major reason most hospitals closed between 2013 and 2017, according to a 2018 study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office. Other factors include a decrease in patients seeking inpatient care.

Unlike in NH, most of the hospitals that scaled back or shut down were in states that did not expand Medicaid under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Hayes says NH’s hospitals are ahead of the curve, including how they manage population health, which refers to the well-being of anyone in their catchment areas. A small rural hospital improvement program grant will support chronic disease “hot-spotting,” where independent hospitals target preventive programs around such diseases as Type 2 diabetes, asthma or tobacco addiction.

One such program targeting chronic illness “hot spots” is at Littleton Regional Healthcare. The hospital participates in the Accountable Care Organization Investment Model for Medicare patients, a partially federally funded program. The program engages patients with chronic conditions in ongoing care to improve wellness and reduce emergency room admissions and hospitalizations, says hospital spokesperson Gail Clark. As this program is new, she adds it’s too early to determine long-term success.

Funding Challenges Persist

There are other strategies afoot to keep people out of the hospital. In NH, managed Medicaid, as opposed to fee-for-service Medicaid plans, rewards hospitals for positive outcomes, with the goal of curbing unnecessary spending.

However, managed Medicaid plans do not produce favorable profit margins.

Maximizing the reimbursement they do get is a key focus at Speare Memorial Hospital in Plymouth, the only other critical access hospital besides Cottage Hospital in Woodsville that remains independent.

One way that Speare Memorial CEO Michelle McEwan accomplishes this is by focusing on quality metrics. Under a fee-for-value payment system, “We don’t want to be in a position where we’re penalized,” says McEwan.

The state moved from fee-for-service to managed Medicaid in 2019 as a means to continue to provide enhanced medicaid coverage in the state. This transition pinched Monadnock Community Hospital ’s bottom line by about $500,000, according to Cynthia McGuire, CEO. Like most small hospitals, she strives for a 1 percent margin, which, at Monadnock, is $800,000.

Though Monadnock Community Hospital generally breaks even, McGuire says, “We’re looking at a deficit, and we’re working now to see what services we can tighten up.”

It’s common for hospitals to land in the red in the first half of a year as they await Medicaid’s disproportionate-share hospital income, which is essentially federal funds that reimburse hospitals for uncompensated care.

Because disproportionate-share hospital payments don’t arrive until May 31, Androscoggin Valley Hospital President Michael Peterson says it puts small hospitals on a “razor-thin and volatile” profit margin.

Anne Langlois, RN, with a patient in Androscoggin Valley Hospital’s maternity ward. Courtesy photo.

Earlier this year, NH’s Medicaid expansion program transitioned from the NH Health Protection Program, where Medicaid reimbursements roughly mirrored those of Medicare, to the Granite Advantage Healthcare Program, with much lower Medicaid reimbursements. Steve Ahnen, president of the NH Hospital Association, says, as a result, NH’s hospitals will lose more than $30 million annually.

Ahnen explains that hospitals receive about 50 cents on the dollar for services they provide for Medicaid beneficiaries. That’s one of many roadblocks that impede small hospitals from turning a profit. Burdensome federal regulations are another.

McEwan points to stipulations around electronic record keeping, such as proving a certain rate of prescriptions are sent electronically; maintaining a patient portal and providing metrics on access; and reporting transfer of patient data to other providers. “I think all of us have seen information technology assume a larger and larger percentage of our expenses,” she says.

It isn’t just the volume of mandates that strain hospitals; it’s the pace of technological upgrades and the challenge of finding qualified IT professionals to maintain them, McEwan says.

Merger Trends

Nationally, around 12 percent of all rural hospitals (380 total) merged between 2005 and 2016. Ahnen says that’s becoming the norm. “This notion that you can have independent community hospitals do all things for all people, on their own, is not really the future of health care,” he says.

In Coos County, four NH hospitals— Androscoggin Valley Hospital, Littleton Regional Healthcare , Upper Connecticut Valley Hospital , and Weeks Medical Center —aligned in 2014 under a common nonprofit, North Country Healthcare .

However, in February, the largest of the four hospitals, Littleton Regional Healthcare, announced its intention to withdraw from the affiliation as of April 1, which led to North Country Healthcare filing a lawsuit. (See sidebar.)

However, in February, the largest of the four hospitals, Littleton Regional Healthcare, announced its intention to withdraw from the affiliation as of April 1, which led to North Country Healthcare filing a lawsuit. (See sidebar.)

While affiliations help hospitals cut costs, Peterson of Androscoggin Valley worries that in Littleton Regional Healthcare’s absence, North Country Healthcare loses its leverage to keep supply costs down.

“It’s disappointing to think we potentially move from collaborators to competitors,” he says, “because while competition is good for certain economies and markets, it’s not always good for health care.”

Affiliations are also a matter of survival, says Ahnen, as NH’s community-based hospitals in remote areas nurture an older and poorer population. One challenge for remotely located hospitals is the dearth of patients on private insurance, says Ahnen. For example, at Androscoggin Valley Hospital in Berlin, roughly 65 percent of patients are enrolled in Medicare or Medicaid.

Even those with private health insurance face high deductibles and copays, says Mooney of Alice Peck Day. When some patients don’t pay their bills, small rural hospitals can’t lean on a steady stream of patients that a more urban locale affords.

Whether 20 or 100 patients walk in the door, a hospital has to keep the lights on 24/7, says Maria Ryan, CEO of Cottage Hospital. And she adds that insurance companies are lowering reimbursement rates or sometimes denying coverage for legitimate procedures. She cites, for example, a patient coming into the ER, thinking he’s suffered a heart attack. The staff runs tests, but, if it turns out not to be a heart attack, the insurer will second-guess the high costs of preliminary tests.

Despite these challenges, Ryan strives to keep Cottage Hospital fees below average. She’d like to streamline the insurance maze, but for now, she zeroes in on simplifying processes for her 300+ employees.

“We eliminate wasteful steps,” says Ryan. In some cases that literally means foot steps. Why have nurses walk back and forth to supply rooms when they can keep medications secure at the bedside in a locked rolling cart? Why force ICU nurses to track down a fax machine in another department when the tools they need can be placed where they need them?

These adjustments may seem like low-hanging fruit, but Ryan says such changes allowed the 25-bed hospital, which has an acute senior behavioral health unit and the North Country’s only trauma center, to stabilize costs and maintain high-quality care.

But, as of 2014, moves to improve processes did little to save one of Cottage Hospital’s most vital services: its labor and delivery center.

Ryan says many of the pregnant women were on Medicaid and the unit was losing about $500,000 a year. “When reimbursements kept getting cut and cut, I could no longer sustain it,” she says. Cottage Hospital is one of nine NH hospitals that have shut down birthing centers since 2000.

Lower birth rates factor significantly in maternity ward closings, says Dartmouth-Hitchcock researcher Timothy Fisher, who is also studying what he calls “maternity deserts.” Fisher is also evaluating the effects on pre-term births, cesarean sections and newborn health, as well as on emergency personnel and hospital emergency rooms.

While these closures may have been an appropriate response to shifting demographics, he hopes policy makers will discuss ways to regionalize care so that pregnant women are not far from a facility that will take care of them.

Fisher says these closures are the “tip of the iceberg,” chipping away at a hospital’s ability to recruit gynecological staff, and therefore the provision of women’s health services, such as access to routine care, contraception and gynecological surgery. When faced with the loss of maternity care, Fisher says young families may also lose available pediatricians and neonatologists. “There’s a ripple effect,” he says.

In secluded areas like Berlin, where the nearest movie theater is 45 minutes away, birthing centers help attract young families.

Littleton Regional Healthcare appears to be one of the few rural hospitals bucking these trends. Due to pending litigation with North Country Healthcare, hospital officials declined to be interviewed and would respond only to an email query. A spokesperson for the hospital states that Littleton Regional Healthcare reported an operating margin of 2.1 percent in 2018 and benefitted the community by $2.5 million.

“Littleton is fortunate to have a robust micro-economy that is not present in the rest of the North Country, which enables us to maintain a favorable payer mix,” Clark states in an email.

Critical Access Status

Rural hospitals with 25 or fewer acute care inpatient beds may be eligible under the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for critical access status, allowing them to receive 101 percent of Medicare costs, although Hayes of the NH Flex Program is quick to point out that this is hardly a windfall.

In NH, 13 hospitals claim critical access status. As McGuire of Monadnock Community Hospital explains, the costs-plus-one-percent payment model is designed for small-volume providers who don’t have many additional resources.

Peterborough harbors one of the oldest demographics in NH, and its Medicare participation inches up by about 2 percent annually, according to McGuire. Since Medicare pays less than commercial payers, McGuire says the hospital retains the same number of patients annually as reimbursement rates decline.

Workforce Concerns

It’s been nine months since Speare Memorial Hospital in Plymouth, which still operates a birthing center, began its search for an obstetrician. It’s also looking for a couple of other critical medical positions, namely a general surgeon and an emergency medicine specialist.

McEwan says the long waits to fill positions drain the existing staff. “Although we do try to bring a locum tenans position [temporary] in to support them as much as possible, that is a very costly way of doing it,” she says.

Recruitment strategies run the gamut. Cottage Hospital employs an agency to recruit nurses internationally. McGuire of Monadnock Community says they often share specialists with another organization.

Peterson of Androscoggin Valley says a remote location and low volume are also magnets for those who’ve been “burning the candle at three ends in an urban location” and are ready for a change in work/life balance. He says the recruitment phase is lengthier than most but the retention is higher.

Overall, hospitals in rural communities face daunting challenges, forcing administrators to find creative ways to keep the doors open, knowing these institutions contribute to the health of their patients while providing the best prescription for the local economy.

Current Issue - April 2024

Current Issue - April 2024