Snowmaking at King Pine Ski Area in Madison. Courtesy photo.

If the response towards climate change continues on its current course, experts say NH’s ecosystem and economy will be dramatically changed, including some of the most iconic elements of our tourism trade.

Leaf peepers may no longer see brilliant reds among the foliage. Moose may disappear from the landscape as they migrate further North and the sea level rise could inundate our beaches.

International experts say we have 12 years to make significant changes. A report release last fall by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns that if governments don’t act soon, greater environmental changes, and devastation, is to be expected.

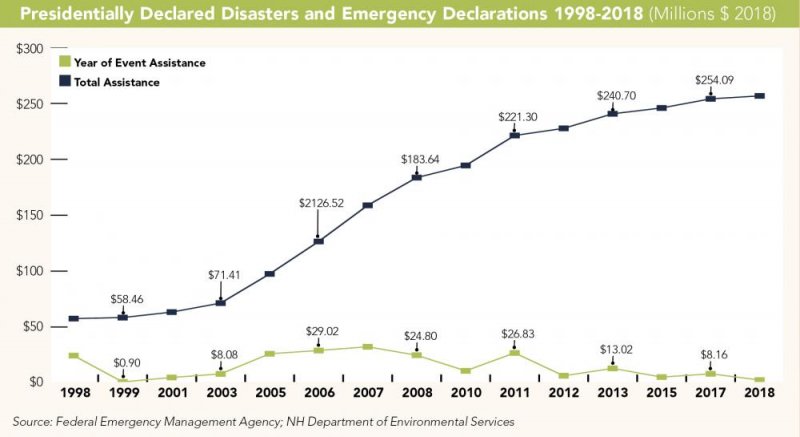

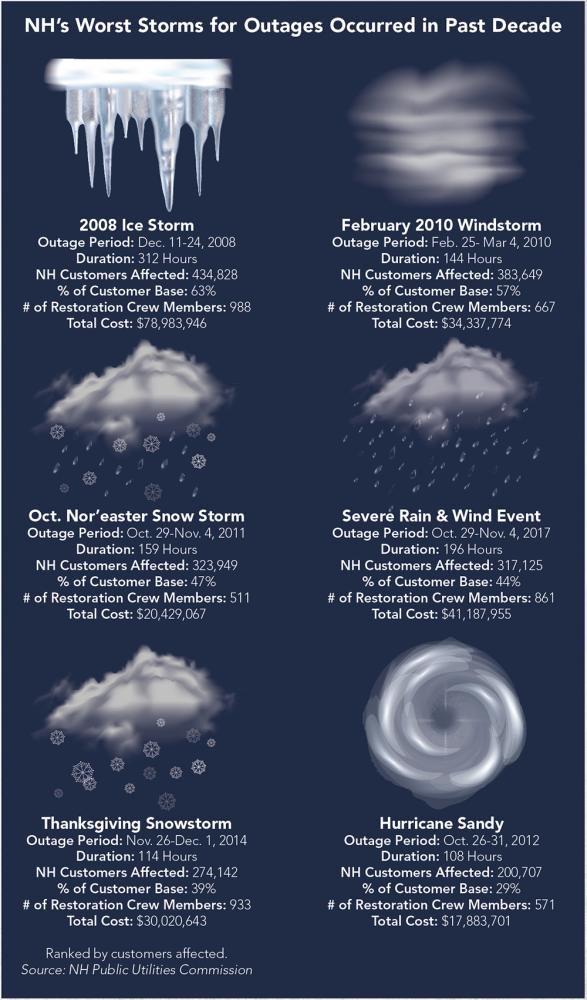

The effects of climate change are already evident. According to the NH Department of Environmental Services (DES), every county in NH has experienced a presidentially declared disaster since 1986, high-tide flooding is occurring on a weekly basis, and trees and wildlife are threatened by warmer winters.

DES Assistant Director Mike Fitzgerald says climate change related events in NH have worsened in recent years. “The real area of improvement is in the attribution science,” Fitzgerald says. “It’s developing in a way that we can see more clearly what’s causing climate change.”

The Fourth National Climate Assessment Volume II, Impacts, Risks and Adaptations in the U.S. (NCA4), released by the federal government last fall, has environmental advocates calling for a renewed commitment and a stepped-up response to address the threats as state and local authorities craft resilience plans.

State Climatologist Mary Stampone, who co-authored the northeast chapter of the NCA4 with lead author Lesley-Ann Dupigny-Giroux, Vermont’s state climatologist, says the report does not offer recommendations. Instead it is an effort to identify the effects that are happening now and how those might transform the future. “There is some good news,” Stampone says. “The northeast region as a whole and New Hampshire have been proactive at adaptation efforts at the state and local level to address the climate change impacts that we were already seeing.”

NH State Climatologist Mary Stampone. Photo by Judi Currie.

Fitzgerald agrees and says the actions NH is taking are improving the outlook including efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by participating in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, adapting to coastal changes and protecting vulnerable areas with changes to regulations and building codes.

In 2008, then Governor John Lynch appointed a bipartisan task force to study the issue and come up with a plan. Fitzgerald says the 29-member panel created NH’s Climate Action Plan, which recommended a 20 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2025 (below 1990 levels) and an 80 percent reduction by 2050. The state has met interim goals.

To achieve those reductions, 29 states, including NH, established a Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) for the percentage of electricity generated by renewable sources. Tom Irwin, vice president and director of Conservation Law Foundation NH, says other New England states committed to higher RPS goals.

New Hampshire committed to 25.2 percent of energy to be generated from renewables by 2025. In Maine the target is 40 percent and in Vermont the RPS calls for 75 percent by 2032. Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island all have targets around 40 percent by 2032.

Dan Weeks, co-owner and director of market development at ReVision Energy, based in Brentwood, says the RPS is a statutory requirement so if the utilities cannot source the percentages they need from renewable energy, they can pay an alternative compliance payment, which funds promotion of renewable energy projects.

Weeks says state goals are too low, especially the solar goal that tops out at 0.7 percent of the RPS. “Because the state threshold is so low, the alternative compliance payments are low, which means the money for rebates are low,” he says.

Weeks adds that renewable energy credits, which have recently sold for $300 per megawatt in Massachusetts, sell for around $5 in NH, which means for businesses considering solar projects there is less financial incentive to do so. Also, Massachusetts boasts 11,000 solar industry jobs while NH has fewer than 1,000.

The entire state spends about $6 billion a year on energy with about $5 billion of it purchased out of state, Weeks says.

“We’re importing energy sources that are the primary causes of carbon emissions and greenhouse gases. We have the potential to meet almost all of our in-state energy needs through resources like sun, wind and water that are clean and renewable. It’s not just the green thing to do, it’s a smart economic decision,” he says.

While there are several bills before the state legislature relating to energy, Irwin says municipal aggregation, also called community choice power, is the most exciting. He says NH was the first state to allow municipalities to purchase bulk power off the market and provide it to their residents, but new legislation would update the statute and make it even more effective.

“The model adopted years ago was opt in. If a community wants to do it, they must market it and have residents sign up.

Other states have an opt-out model where everyone is automatically a customer of the municipality and can opt out,” Irwin says. “This has been very effective in Massachusetts.”

Are Warmer Winters So Bad?

Sam Miller, a professor of meteorology at Plymouth State University, says temperatures are increasing more rapidly in the northeast. “As you get closer to the pole and farther from the equator, regions are warming faster than lower latitudes,” he says. “We are warming faster than Florida.”

Miller says a warming of the atmosphere makes surface temperatures higher, which increases evaporation. So even with more precipitation, we will see more intense droughts in the future. “We are going from having one 100-degree-plus day to 20 100-plus days” annually. The warming of the atmosphere also increases its ability to hold water resulting in more winter precipitation, likely in the form or Nor’easters with a rain-snow mix.

While fewer frigid days may sound appealing, Stampone says it is important to understand how critical cold snowy winters are to the state’s ecosystem. “Cold and snow can regulate insect populations like ticks and tree pests,” Stampone says.

“Snow is an insulator and a good snowpack protects the root systems of trees while snow melt replenishes our groundwater going into the growing season.”

“It is easy to say, ‘I wish winter would end,’ but we really need winter to happen,” she says. “Everything is adapted to a traditional New England winter. As [climate] changes, it impacts not just winter but other seasons as well.”

Mark Green, associate professor of Hydrology in the Center for the Environment at Plymouth State University, says higher temperatures will create foliage more like the Carolinas with trees browning in the fall rather than blooming into a potpourri of fall colors. “We will see a migration of our [tree] species in a northern direction and we will see more southern species here,” he says.

Stampone says how successfully a species survives these climate trends depends in part on whether it can migrate, how fast the change is happening and whether it is able to find suitable habitat. “Animals can walk but trees can’t, so they migrate a lot slower. We have already seen change, including species moving in to the detriment of our native species,” she says.

That includes the hemlock wooly adelgid, accidentally brought to the U.S. from Japan in 1951, which decimated hemlock trees. More recently the emerald ash borer decimated ash trees. Such pathogens and pests would have been killed in a typical NH winter but are able to survive a milder season. “Winter would have hit them so hard they could not reproduce in the spring. That’s no longer the case,” Green says.

Cold New England nights are also critical for trees in other ways. Green says the bright colors of fall foliage come from warm days followed by cool nights—the larger the difference, the more the foliage can really pop. Those swings also get the sap running. An early spring causes trees to bloom prematurely and sap gets diverted to feed the tree. Weeks says where NH once had the ideal climate, Canada is now the largest maple syrup maker, with Quebec producing 70 percent of the worldwide supply.

A shorter winter is also a serious challenge for the state’s moose population. Kristine Rines, a certified wildlife biologist and the moose project leader for NH Fish and Game says as winters have become shorter, it increases the time ticks have to attach to a moose, causing the number of ticks to increase exponentially.

She says the cows lose so much weight they don’t ovulate and it is even harder on the calves. “If you get enough ticks, about 37,000, which we do see, they remove the entire blood volume of the animal. Those little babies don’t have enough mass to survive that.”

Rines says they have seen as many as 100,000 ticks on one moose. Part of the problem is location. She says moose evolved in the north where ectoparasites were rare so they don’t have a grooming response as most others animals in the region do.

“Ticks are only part of the problem,” Rines says. “They are a northern based species and New Hampshire is on the southern end of that range. As our climate changes, we are going to lose those species. They simply won’t be able to adapt.”

In the 2012/2013 season, NH Fish and Game recommended the state issue 275 moose hunt permits. For Fall 2019, they are recommending 51.

Rines says in the late 1990s there were about 7,400 moose. That dropped to about 4,500 by 2013 and today there are only about 3,300 moose in NH.

She says there will undoubtedly come a time when there will be no moose hunt.

The Backyard Effect

Lawrence Hamilton, professor of Sociology and senior fellow in the Carsey School of Public Policy at the University of NH in Durham, first espoused the idea of the backyard effect. In 2007, Hamilton learned through research that wintertime warming is a serious challenge for ski areas and whole regions that depend on winter tourism. The “backyard effect” showed that urban snow conditions affect the number of skiers showing up at resorts. Snowmaking alone is not enough to draw crowds.

Shorter, warmer winters are a huge issue for ski areas and a threat on multiple levels to winter recreation. Jessyca Keeler, executive director of Ski NH, a statewide association representing 32 alpine and cross-country resorts, says the organization is always looking for opportunities to help members achieve greater sustainability.

“While it’s true that climate change is a top concern amongst many in the ski industry, ski areas in New Hampshire have had a long time to learn to adapt to changing weather patterns,” Keeler says. “As early as the late 1930’s when the industry began in this state, operators looked for ways to make snow during seasons when Mother Nature wasn’t cooperative.”

Keeler says snowmaking is key to a four- to five-month ski season and the efficiency of snowmaking systems has increased significantly, effectively allowing ski areas to make twice the amount of snow in half the amount of time than they did just a decade or two ago.

Keeler says most ski areas are also three- to four-season operations now, which is not purely a response to climate change.

“It makes good business sense for resorts to utilize the infrastructure that they’ve built over the years to serve a summer, spring and fall clientele as well.”

Adaptation and Resilience

As communities and the state continue to follow the science and prepare for change, Fitzgerald says DES is taking a wholistic approach and has integrated climate change into all department programs. “We have to keep up efforts to achieve our climate goals without harming the economy,” he says. “As we pursue the goals there will be some improvement and we’re hoping the clean energy economy will offset the cost.”

According to Chris Skoglund, the climate and energy program manager at DES, the state must avoid the unmanageable and manage the unavoidable, all while keeping a close eye costs. He says in developing the Climate Action Plan, the state worked with Climate Solutions New England to share ideas and glean knowledge. “We used only state resources when every other state used consultants. Our program is stronger because we’ve got buy-in,” Skoglund says. “The plan is in the people and the intellectual capital remains in the state.”

A cornerstone of the plan is adaptation; adapting to changes in the environment and developing a plan for resilience. “We have to look at the difference in the data we’re seeing,” Fitzgerald says. “A 500-year storm is now happening every 10 years; we’re seeing much greater impact. So, when we rebuild, we have to adapt to this new reality.” He says there’s a lot at stake as 35 percent of meals and rooms revenue comes from coastal regions.

Sherry Godlewski, the resilience and adaptation manager for DES, is a member of the NH Coastal Adaptation Workgroup (CAW); which includes representatives from the federal, state, regional, academic, municipal, business and nonprofit sectors. CAW has secured more than $7 million in grant funding to bring local data and research, planning tools and technical assistance to more than 150 community members.

NH Coastal Adaptation Workshop Coastal Climate Summit. Courtesy photo.

She says CAW hosts public workshops and an annual coastal climate summit. As a result, communities have made numerous changes to master plans, hazard mitigation, zoning and incorporated sea-level rise into development projects.

NH Coastal Adaptation Workgroup focusing on dune restoration.Courtesy photo.

Godlewski is also a member of the Upper Valley Adaptation Workgroup, which she says has different funding but still focuses heavily on education. “We are making people in the area aware of the potential impacts and solutions,” she says. “We’ve learned that municipal decision-makers like to learn from each other, which can build strong social capital and support for legislation.”

Godlewski says State Sen. David Watters established a Coastal Risk and Hazards Commission, which issued 37 recommendations to build resilience and understand the vulnerability. Watters introduced a measure to extend the community revitalization tax relief program (known as 79-E) to coastal properties subject to storm surge, sea-level rise, and extreme precipitation. The new law enables municipalities to designate Coastal Resilience Incentive Zones and use tax abatements and other incentives to support preparedness.

“Adaptation is very local,” Godlewski says. “In Hampton the tidal chart for 2019 shows 56 regular high tides over the flood stage. More than once a week street flooding occurs. Residents are very concerned because they can’t park their cars in front of their homes.”

Godlewski says they moved the cars but since homes can’t be moved, any new construction now requires two feet of free board at the bottom of the home, allowing flood water to pass through without damaging the house.

Skoglund says sometimes people don’t appreciate the scope of the coastal risk. “They know that New Hampshire has a pretty short coastline when you look at it on a map; but when you take into account Seabrook and Hampton harbors and Great Bay, you’re talking about 150-mile estuarine coastline.”

A report issued in June by the Union of Concerned Scientists (Underwater: Rising Seas, Chronic Floods, and the Implications for US Coastal Real Estate) projected that by 2045, nearly 2,000 NH homes could be chronically inundated by floodwater.

Kristy Dahl, senior climate scientist and co-author of the report, says chronic inundation is flooding that happens on average every other week.

Sharing Solutions and Successes

Helping businesses to become more sustainable is a prime mission for NH Businesses for Social Responsibility, a nonprofit with about 200 members.

A segment of its 2019 spring conference on May 1 focused on innovative climate action approaches and showcased stories from Stonyfield Farm in Londonderry, W.S. Badger in Gilsum, and Seventh Generation in Burlington, Vermont. Presenters Jess Baum, sustainability manager at Badger, and Lisa Drake, director of sustainability innovation at Stonyfield, say the stories were meant to inspire and help businesses answer the question, “Where are my impacts and what is my unique opportunity?”

“We hear about this gigantic problem and it snowballs, we feel powerless,” Baum says. “But this huge catastrophe of our time is really an opportunity to do good.” She says they asked conference attendees to look within their companies to prioritize and find ways to take action.

Drake says businesses often count climate change among their greatest concerns, but they don’t know what to do about it.

“We want to inspire people to broaden their thinking. Stonyfield started out as a way of educating people about sustainable agriculture and family farming, not about selling yogurt.” She says they will stress the importance of being resilient and not just sustainable. For Stonyfield and Badger it is having an agricultural supply chain that is regenerative. Baum says sustainability is keeping things as they are, while “regenerative agriculture is going a step beyond, making it better than you found it. The activity increases the health of the ecosystem.”

Baum says climate reports underline the urgency of the situation. “We don’t want people to be afraid, we want to share stories of success and show that the collective can change the world.”

Taking Back the Narrative

A study by Yale University released in January, “Climate Change in the American Mind,” shows that the proportion of Americans who think global warming is happening and worry about it has increased sharply over the past five years—with the largest increase among conservatives.

Building upon the increased understanding of the risks, Erin Allgood, social change consultant at ELA Consulting, and Lila Kohrman-Glaser, co-director of 350 NH, a statewide climate action nonprofit, will present a session at the NHBSR conference about taking back the narrative on climate and energy.

“We will focus on how our values inform the narratives that we tell and how we can use our collective voice to drive positive change,” Allgood says.

Kohrman-Glaser says the dominant narrative in the past has been, “Is it real? But as a society at large and in New Hampshire we moved past that narrative. What we say now is, ‘what can your business do to have an impact on this climate crisis?’ And we really ground that question in the fact that businesses have a stake.”

She says they intentionally use the word crisis, “Academics say we have about 12 years to address this. ... .Many New Hampshire businesses have signed onto the clean energy principles, I feel we have enough interest to move the needle.”

Allgood says the crisis is bad for everyone in NH, not just 1,000 homes that regularly experience flooding. “Climate action is good for businesses in New Hampshire, it means jobs and protecting us from the impacts.”

Editor’s note: Next month, businesses share their innovative approaches for managing resources and adapting to climate change.

Current Issue - April 2024

Current Issue - April 2024