It was one of the signature proposals in the two-year state budget Gov. Chris Sununu unveiled in February—a plan to combine the state university and community college systems under a single board of trustees as the first step toward a complete merger of the two organizations.

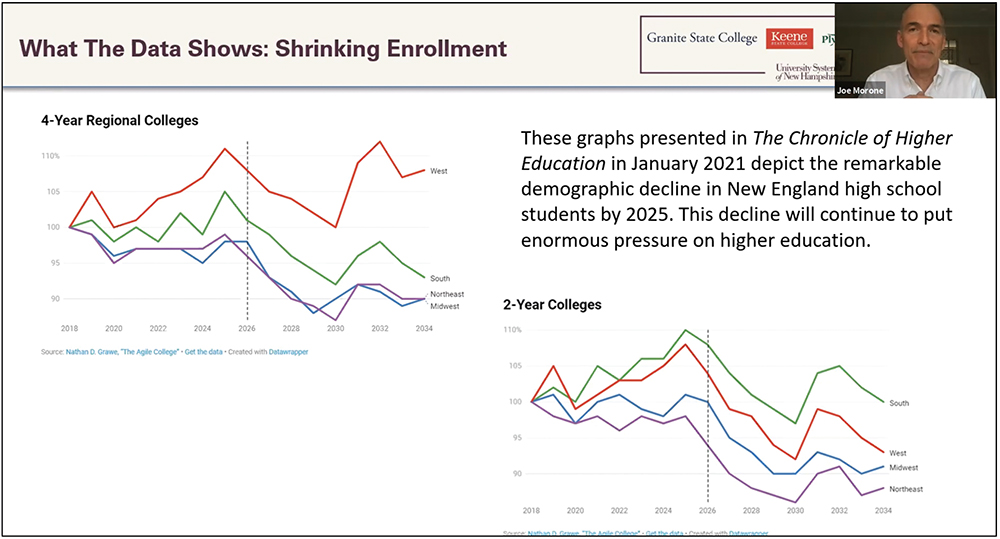

In light of a significant decline in high school students over the next decade, limiting the pool of college applicants and putting more financial pressure on higher education institutions, the governor called the proposed merger “an opportunity that can wait no longer.” He described it as “the future of higher education” and said it would benefit every post-secondary student across the state.

Yet soon after the merger idea entered the legislative process, it flopped with a resounding thud. Much to the disappointment of the governor, the House decided to amend his proposal, calling instead for the creation of a “New Hampshire Higher Education Merger Assessment Commission” with $1.5 million to study the idea and maybe begin implementation next year.

While expressing disappointment in the House vote, Sununu advisers anticipated a better reception in the Senate, where Senate President Chuck Morse, R-Salem, has been one of the governor’s most steadfast supporters.

But it was not to be. The Senate would not even entertain the House amendment, and House negotiators didn’t put up much of a fight. Sununu actually got more support for the idea from Democrats in the Senate when Sen. Lou D’Allesandro, D-Manchester, proposed an amendment of his own.

“I offered an amendment to create a real commission to study it … a real commission made up of educators who had knowledge of both systems,” says D’Allesandro, “with a $5 million appropriation to provide what was needed to do a real study.”

That idea didn’t even come to a vote. “It couldn’t even get a second in Finance Committee,” he says. “I knew it was all over at that point.” That was in May, when the Senate was wrapping up budget work in committee.

Unrealistic Optimism

Just a month earlier, on April 22, one of Sununu’s top advisers, State Budget Director Matthew Mailloux, appeared in a webinar about the merger hosted by the Business and Industry Association. His comments illustrated the disconnect between the governor’s office and lawmakers of his own party on the issue.

“There is broad bipartisan agreement that this is the right path. There is broad buy-in that this would be good for New Hampshire and good for our students,” Mailloux told the online audience of BIA members. “We’re confident that the Senate will work with the governor and ultimately get something passed here before the end of June … not a commission to evaluate and beat around the bush, which is what we see the House proposal ultimately leading to.”

If there was a “broad bipartisan agreement,” there was certainly no evidence of it in the final budget that Sununu signed into law, which contains no mention of a study committee or any steps toward a merger.

Still, Sununu remains committed to the idea. “This merger would have been a win for students, families and employers across our state,” he said in a statement to Business NH Magazine. “While it is unfortunate the legislature chose to not move forward with this 21st century merger, I remain committed to ensuring a sustainable higher education system in our state because the stakes are too high to remain stuck in the past.”

Rarely does a proposal so valued by a popular Republican governor fail to gain any traction in a state legislature dominated by his party. Many of the lawmakers interviewed for this article say more advance work by the governor’s office would have revealed the plan as drafted was dead on arrival. “I never heard anyone say they thought it was a good idea,” says Sen.

John Reagan, R-Deerfield, co-chair of Senate Finance. “I remember generally there just was no enthusiasm for it.”

Maybe Next Year

Senate Majority Leader Jeb Bradley, R-Wolfeboro, is a little more sympathetic to the governor’s position.

“I applaud the governor for thinking outside the box,” he says. “I thought the idea had some merit, but it needs its own hearings and its own legislative process,” as opposed to being part of the state budget. “We [the State Senate] decided that it should come in as a separate piece of legislation, which I suspect will happen next year. We’ll see what happens at that point.”

Bradley, who knows the will of the GOP caucus as well as anyone, says there is a fear that both systems would not benefit equally from a merger. “A lot of questions got raised, particularly by the Community College System. There was a fear they would get swallowed up by the university, which would not be a good outcome because the Community College System is well-run, efficient and their cost basis is really good,” he says. “It could work if the Community College System had equal say or veto power over what might happen in a merger, but I think there was some fear that the larger university system would swallow them up.”

Despite the failure of the proposal this year, there is broad agreement that something needs to be done to help all post-secondary institutions deal with the fiscal tsunami they’re facing due to demographic changes, declining enrollment, rising costs and the emerging realities of a post-COVID world.

“Something’s got to happen. Both the university system and the community colleges are in trouble. There’s no question about it. Look at the recent situation with Keene State,” says D’Allesandro, referencing the college announcing in early June another round of faculty buyouts to help cope with a $14 million deficit.

The Idea Fades Away

As the horse-trading surrounding the budget drew to a close, the merger proposal simply faded away, with little to no mention in the media or elsewhere.

“Rather than discuss it, the Senate just swept it under the rug. And the governor just backed away from it. I really don’t know why. It was his signature proposal,” says D’Allesandro. “For the House, I think it was a throw-away. They got their abortion restrictions and [restrictions on] divisive language, and Sununu got his family leave, which the House didn’t want.”

The university system is regarded by many in the Republican caucus, both House and Senate, as an organization rife with administrative bloat that serves as a breeding ground for progressive voters. The community college system, on the other hand, enjoys a favorable reputation on both sides of the aisle. Many lawmakers would just as soon continue to deal with each separately, especially when it comes to funding.

“You can look at it and say the community colleges receive more respect from the legislature than the university system because they contain costs and offer programming more acceptable to the legislature with the focus on the vocational areas,” says D’Allesandro.

Jim Roche, the outgoing president of the Business and Industry Association, says his organization was strongly in support of the merger and disappointed in the outcome. “The BIA made a pretty overwhelming decision to support this,” he says.

“We represent the business community and businesses face these kinds of tough choices all the time. The legislature decided to avoid them for the time being.”

Effective Opposition

The opposition, primarily among stakeholders, was effective and largely behind the scenes, Roche says. “In the early going, the community college system did a good job of being obtuse. They didn’t want to upset the governor by coming right out and saying we oppose this, so they started raising concerns. ‘Have you thought about this? Have you thought about that?’ It became a death by a thousand cuts,” he says.

In her presentation during the BIA webinar, Community College Interim Chancellor Susan Huard was less enthusiastic about the merger than budget director Mailloux or Joe Morone, board chair for the university system.

Joe Monroe, USNH board chair, presenting at the BIA webinar.

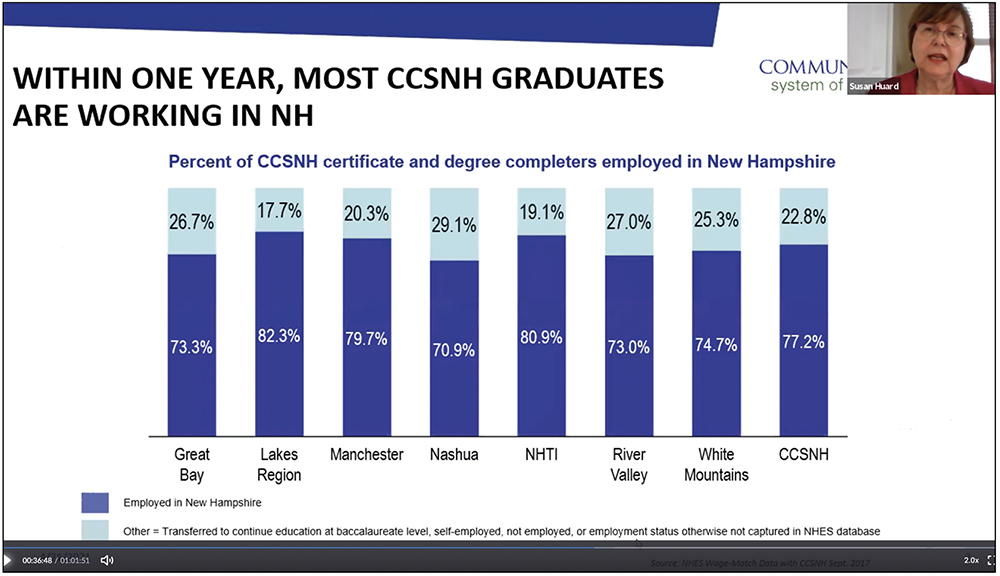

While Morone charted all the factors that pose an existential threat to UNH and its cousins in Keene and Plymouth (See story on page 30), Huard explained why the seven community colleges are not as severely threatened. She outlined that the Community College System is not as reliant on 16-to-21-year olds as four-year colleges as 38% of its students are between the ages of 21 and 25 and 40% are age 26 and older. The majority of the Community College System’s students—76.4%—are part-time students. Most—93%—are from NH and most land jobs in NH within a year after graduation.

“The Community College System has been working to make ourselves viable for years and years by responding to the needs of the state,” and its workforce, Huard says.

Huard says the CCSNH board is in favor of looking at the idea of what it would mean to merge with USNH but is much more cautious about the proposal than USNH. “We are very concerned about what will happen in merger conversations to our mission,” she says. “There are many states where mergers have occurred that found they had to go back after five years and reinstate the community college system as a unique entity. Nevada was the latest.”

Susan Huard, CCSNH interim chancellor, presenting at the BIA webinar.

She points out that the CCSNH board is not alone in their concerns. The education subcommittee, tasked with examining the governor’s proposal, developed 60-plus questions that need to be addressed, including values, accessibility and how a merger would be implemented.

Given the intensity of stakeholder energy surrounding the issue, Roche is not optimistic about the legislature revisiting the matter next year.

“The legislature is going to have to set up an independent commission that has the authority to make this happen, because it may include closing some colleges,” Roche says.

Current Issue - April 2024

Current Issue - April 2024