John Patti, Catholic Medical Center’s executive director of support services, left, shares N95 masks with Kevin Healey, Elliot Hospital’s emergency management director. Courtesy photo.

John Patti, Catholic Medical Center’s executive director of support services, left, shares N95 masks with Kevin Healey, Elliot Hospital’s emergency management director. Courtesy photo.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed not only the vulnerabilities of the human body but the weaknesses of the health care system. From a “just-in-time” system of delivering supplies that was better suited to industry than to medicine to a reliance on foreign-made equipment and a disjointed regulatory structure that hampered health care delivery, the frailties of the system were suddenly and painfully on display.

Industry executives say the pandemic has also exposed the state health care system’s resilience and unity in the face of challenge. They note that it is likely to produce some permanent changes in everything from how medical appointments are conducted to how hospitals are designed.

“The other side of adversity is opportunity,” says Susan Reeves, the recently named executive vice president of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon.

Supply Chain Challenges

The pandemic disrupted the medical supply chain for items like personal protective equipment (PPE) and medications. Hospitals were scrambling—and often competing—because of limited availability. Heftier price tags and questions of product quality followed.

“Our primary objective is to keep our patients and our workforce safe, and not knowing the duration of the pandemic and not understanding how fragile the supply chain was… shocking,” says John Z. Jurczyk, president of St. Joseph Hospital in Nashua. “We thought there was a stockpile of personal protective equipment that we could all draw on, and that stockpile got depleted pretty darn quickly.”

After the federal administration invoked the Defense Production Act this spring to encourage manufacturers to transition to making emergency supplies, “we had to go out individually to source PPE and pay 30 times the price,” Jurczyk says. “We ordered ventilators at the beginning of the pandemic, as well as hooded CAPRs (controlled air purifying respirators), and we’ve never received them.”

He says a friend in another NH health care organization expressed excitement about the masks his facility was receiving from a foreign supplier, only to learn when the shipment arrived that the masks were not health-grade.

Tom Mee, CEO of North Country Healthcare, an affiliation of four medical facilities in the state’s White Mountain region, says the pandemic “exposed how vulnerable we are to medical supplies such as personal protective equipment that are manufactured outside the U.S., notably China.”

When his organization started running out of PPE and sought to purchase some, “it was at grossly inflated prices. N95 masks were going for a couple dollars apiece when they were mere cents before. Medications, as well. We ran into all kinds of shortages of medications and basic supplies because those things are made offshore.”

Reeves of Dartmouth-Hitchcock notes that even before the pandemic, the health care industry “on any given day had a number of drug shortages.”

“So when all of a sudden it escalates because patients need a certain type of medication, because we have drug shortages just as a way of doing business every day, those become even more magnified,” she says.

Dr. W. Gregory Baxter, president of Health Care System in Manchester, says the need for disposable gowns at Elliot Hospital was so acute at one point that a member of the ICU nursing team created a template for making them. “I think we produced thousands,” he says, adding that the global supply chain had diminished to nothing or providing “garbage” product. “That was the best we could do.”

He says while just-in-time delivery of materials may be efficient for the manufacturing sector, it does not work for “our current health care model [that] requires us to run at 90 to 100 percent capacity.”

Likewise, Cynthia K. McGuire, president and CEO of Monadnock Community Hospital in Peterborough, notes that supplies “now come from a global-based manufacturing system, which is impacted significantly during times of natural disaster or, in this case, the pandemic.”

Monadnock Community Hospital has been able to get by largely through contributions and donations of supplies from local businesses “and for that we are extremely grateful,” she says.

What’s needed, industry leaders say, is full transparency about the type and availability of equipment in any national stockpile, a move away from the just-in-time supply mode to one that offers more inventory and less dependence on federal or international suppliers. “I think every state should have its own emergency stockpile and not depend on the federal government,” says Dr. Joseph Pepe, president and CEO of Catholic Medical Center in Manchester.

Catholic Medical Center operating room staff trade in forceps and clamps for scissors and sewing machines to make masks for co-workers. Courtesy photo.

Jurczyk notes that health care workers caring for COVID-positive patients can go through 20 pairs of gowns and gloves per day, per patient. “We need to be looking at making sure we have a three-month supply,” he says.

Cooperation among all stakeholders is also critical, those leaders say. “I would like to better understand how local organizations like Elliot and the state of New Hampshire and the federal government all interrelate on things like a national stockpile,” says Baxter. “I’d like to understand that better, and what our community and state leaders can do and what we can partner on.”

Testing Needs

Another challenge posed by the pandemic has been the lack of quick and reliable tests for illnesses like COVID-19. “The ability to have rapid onsite testing is still elusive,” says Jurczyk.

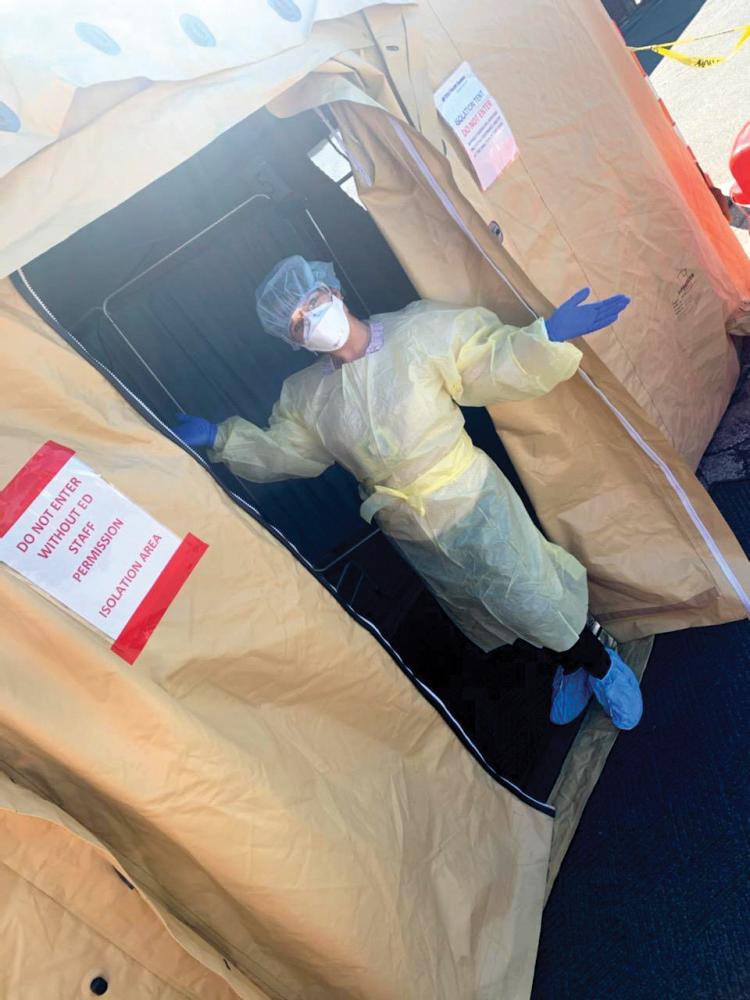

A COVID-19 testing area at Elliot Hospital. Courtesy photo.

A COVID-19 testing area at Elliot Hospital. Courtesy photo.

St. Joseph uses a rapid testing system approved by the federal government, “but a lot of our clinicians have concerns about the sensitivity of the system,” he says. “There is a higher rate of false negatives. … That means you’re taking a little more risk in exposing your workforce to the virus.” Because of that, the system is only used at St. Joseph in emergencies, such as a trauma case.

While the hospital is able to get reliable test results in 36 hours, “the fact that we can’t have immediate test results like a finger stick or an oral swab and know within an hour whether that person is COVID-positive, that’s tough,” Jurczyk says.

Welcomed Changes

The pandemic has also produced or hastened a number of changes that health officials would like to see made permanent.

In April, for example, Gov. Chris Sununu loosened the state’s licensing rules to increase the number of practitioners available to serve patients during the pandemic, allowing them to work at multiple health facilities in the state if credentialed in one, and permitting out-of-state medical workers to practice here.

That came on the heels of an emergency order that required all insurance carriers and benefit plans to allow in-network providers to deliver services via telehealth, or virtual office visits, using video, audio or other electronic media. It also required that reimbursement rates for those telehealth visits be no lower than in-office services.

“I think telehealth has increased, but only because executive emergency orders had to take place to give relief from privacy laws,” says Pepe. “I think these policies should be made permanent once the crisis is over. Crossing state lines, we learned that regulatory burdens limiting the scope of licenses should be looked at to maximize flexibility while ensuring safety.”

In fact, most medical facilities in the state were exploring telehealth long before the pandemic though “some barriers were in the way,” says Baxter. “There were questions from the payment community [about] how to be reimbursed. Then COVID came along and over a weekend or a week and a half, we went from doing almost no telehealth to doing hundreds a day.

We learned a lot. I think that part of our health care toolbox is going to stay.”

Telehealth has also proven popular among patients. “Now many of our patients are discovering that they have the best of both worlds,” says McGuire. “They are learning how easy it is to connect with a trusted family physician from a computer or cell phone without having to leave the safety of their homes. Many patients are finding this telehealth approach to be a preferred option for care.”

With the majority of outpatient psychiatric consults at Elliot now conducted remotely, “there are fewer no-shows,” says Baxter. Mee, whose North Country Healthcare network includes Androscoggin Valley Hospital in Berlin, North Country Home Health & Hospice Agency, Upper Connecticut Valley Hospital in Colebrook and Weeks Medical Center in Lancaster, similarly reports “increased compliance with telehealth, less cancellations.”

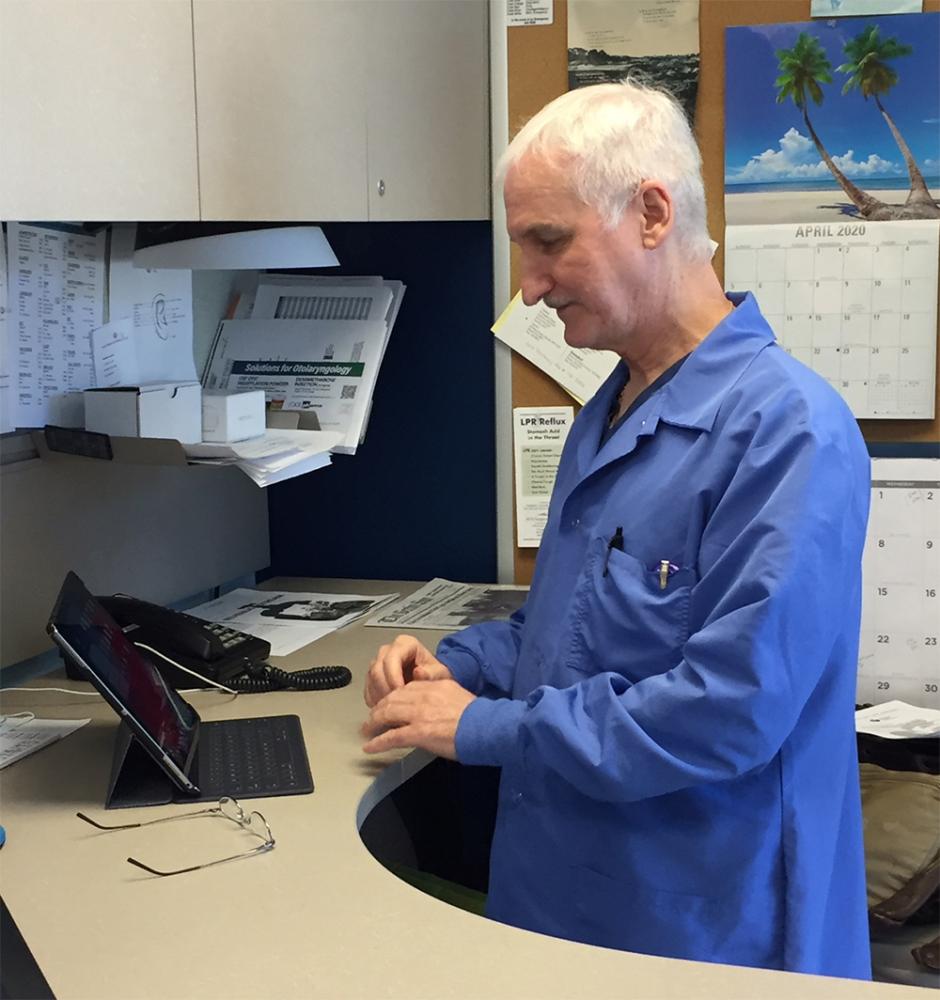

Dr. Richard Kardell of North Country Healthcare consults with a patient online. Courtesy photo.

But telehealth comes with challenges. “Some individuals, particularly in a rural state, don’t have internet available to them or cannot afford a cell phone,” says Reeves. “So we still have some infrastructure development to accomplish to be sure we can reach everybody who wishes to have their health care needs met in this way.”

But once available, telehealth can be lifesaving to residents of rural communities “where having access to specialty consultants is limited,” says McGuire.

Of course, doctors and patients are not the only ones who have turned to remote communication during the pandemic. Many non-medical workers, like office staff, have been consigned to working at home since the crisis began, and many are likely to continue to do so when it’s over.

“I think the number of offices we need is probably going to change with fewer offices and more people working remotely and coming together at certain times,” says Baxter. “If all of that helps us lower the cost of delivering care, that’s great, but it’s hard to know how it’s working with a lot of parents having to home-school,” Jurczyk says, adding officials at St. Joseph’s are already discussing whether to bring office staff back onsite when the pandemic is over.

Likewise, Pepe anticipates “more digital education, virtual events instead of in-person conferences. It’s a better use of time, and it’s more environmentally friendly.”

At Dartmouth-Hitchcock, Reeves says a task force is taking a hard look at remote work, everything from how it would work for those with children to how to provide ergonomically appropriate desks, with an eye to producing recommendations and understanding “what are the supports people need to work remotely and to do it efficiently and effectively.”

Other changes to hospital workspace, meant to protect patients and staff during the pandemic, may also become more commonplace once it is over. Many of those measures seek to reduce or eliminate the time people spend in enclosed spaces with others.

“Nurses have known for years that any number of beds in a room beyond one presents a challenge, but we still have a lot of facilities with multi-bed rooms,” says Reeves. “Now, in an age of pandemic and infectious disease transmission, we are really recognizing that having no more than one patient in a room is going to be the ideal situation.”

Dartmouth-Hitchock’s planned 212,000-square-foot expansion, while in the works long before the pandemic struck, will feature private rooms with negative air pressure, preventing airborne diseases from escaping the room and infecting others.

McGuire says Monadnock Community Hospital implemented a centralized scheduling program for radiology, laboratory and other key services that reduces wait times for patients. “While we had been working on this centralized approach, the pandemic helped us to speed up the design and roll out the initiative quickly,” she says.

The hospital has moved to ensure that “even our HVAC systems will soon incorporate leading-edge, ion-generating technology to help eliminate airborne germs or viruses,” she adds.

Once the pandemic struck, Pepe says Catholic Medical Center was quick to isolate COVID-positive patients in dedicated units, switch many office visits to telehealth and otherwise limit possible contact with infected individuals.

“I think these are changes that need to be around for the long term,” he says. “I think all new hospital construction should include all those things that we struggled to do, isolating infectious patients and protecting staff while allowing normal operations to proceed unhampered. We need more negative pressure isolation rooms, built-in safety dividers on ICUs or other units instead of having whole units close down.”

The pandemic has also introduced some staffing concerns, forcing hospital administrators to address such things as travel restrictions for employees. At St. Joseph Hospital, a worker who travels outside New England must quarantine upon return, according to Jurczyk. “That makes the workforce very tenuous, especially the smaller departments,” he says. “When you have a department that has five full-time equivalents and two are traveling, you’re looking at ‘how do I continue to provide this service?’”

And health officials are already discussing whether to require employees to get inoculated once a vaccine is available, especially since that vaccine is likely to have been brought to market hastily. “We’re talking about a first-generation COVID vaccine through expedited procedure,” says Mee.

Rural Hospitals Attract Talent

Many communities face shortages of health care professionals, and those shortages have traditionally been felt most acutely at rural critical care hospitals that often cannot compete with salaries and amenities offered by larger hospitals in urban settings. But COVID-19 may be changing that.

Memorial Hospital in North Conway would normally attract a handful of applications for open positions but has been inundated with candidates since the pandemic began, particularly from hard hit areas like New York and Boston as well as Southern NH.

Matthew Dunn, chief medical officer, who oversees recruiting for the hospital, says while the natural beauty of the White Mountains can be a draw, it’s not for everyone. But the past few months have brought a significant change in the number of applicants and who is applying.

“We’re getting applicants from major metropolitan areas working for some of the largest and most respected health care organizations in this country,” Dunn says, explaining the pandemic has health care professionals reassessing their career choices, and they are now ready to put quality of life first. He says he even knows of two physicians who moved to the area from out of state before even securing a job.

Across the board, Dunn says applications for positions at Memorial Hospital have increased by 30% or 40% since late April. Dunn says many rural hospitals attract applicants just out of medical school looking for their first job, but the applicant pool now includes experienced clinicians and physicians from major medical centers. And while there continues to be a shortage of nurses, he expects to see the same trend with those positions soon.

Dunn says a primary care nurse practitioner position posted last year attracted a handful of applicants over the course of a year. Another nurse practitioner position posted at the end of March attracted 29 applicants by mid-July. As of mid-August, he had three physicians and a nurse practitioner expected to start new positions at the hospital in the next six weeks. “It is a significant change,” Dunn says, adding this trend should have some staying power. “We’re seeing a lot of talented providers and excellent candidates coming into our communities. It’s pretty exciting.”

Strengths and Weaknesses

“I think it (the pandemic) has solidified our confidence in our ability to respond to an incident,” says Mee. “We transformed hospitals from something open to visitors and friends and family to being shut down in a matter of a week.”

Teamwork, whether within local communities or among hospitals throughout the state, has been another source of pride to many. Reeves says she has been impressed by “the way that the hospital community, facilitated by the Hospital Association in New Hampshire, came together as one to really say ‘none of you will suffer disproportionately because of this.’”

“All 26 hospitals were on the phone together, helping the commissioner for the Department of Health and Human Services [on] how to develop standards of care,” she adds. “The hospital community is the safety net for New Hampshire and we sure demonstrated it.”

Jurczyk says organizations came together at the local level as well “We’ve seen tremendous cooperation among health care organizations in Nashua, despite the fact that many of us serve the same populations and compete in the same space,” he says. “The pandemic showed how we could work together in a collaborative way and put our business interests on the back burner. It speaks volumes.”

All say more vigilance is needed to avoid future pandemics. Jurczyk calls for more investment in public health, surveillance and contact tracing. “We have a lot of preparedness around catastrophic single events, but we need to have more preparedness around infectious events,” he says.

And all agree that preparedness cannot come too soon. Warns Pepe, “If we ever have a pandemic as lethal as the rabies virus and as communicable as measles, it could well wipe out half the population.”

“We know this will happen again,” he adds. “We don’t know when, but we know it will happen again.”

Current Issue - April 2024

Current Issue - April 2024